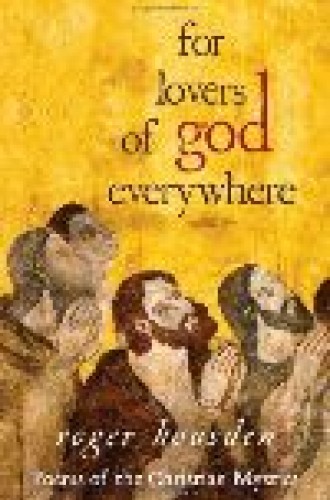

For Lovers of God Everywhere: Poems of the Christian Mystics

It’s almost a job requirement for poets: accept the fact of being far removed from mainstream artistic culture. We poets are happy—ecstatic, really—to cultivate a few hundred thoughtful readers, and we have developed a thick skin toward the widely repeated remark that more people today write poetry than read it.

But there is a contrary development of something resembling a secret society of verse. Though I enjoy some of Billy Collins’s witty poems and the forged, consonantal lines of Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, I reserve special admiration for those poets who, in the words of Hamlet, “pleas’d not the million, ’twas caviare to the general.” Those poets for me would include Mary Sidney, Thomas Lovell Beddoes, Edward Thomas, Emma Lazarus, Patrick Kavanagh and Miklós Radnóti. Each poet has a personal lyrical pantheon, and the very speaking of the names of these cloaked, admired ones emits a whiff of quiet knowing, of meek superiority.

I begin with all of this to justify, as much as I am able, the suspicion I have held for the past half-decade of a peculiar self-improvement, poetry-for-Every man banner—the one waved in Susan Wooldridge’s Poemcrazy: Freeing Your Life Words, in Kim Rosen’s Saved by a Poem: The Transformative Power of Words and, more pertinently here, in a growing empire of tastefully designed and shrewdly marketed poetry anthologies edited by Roger Housden. At my local book superstore, Housden’s books take up a tenth of the limited shelf space reserved for poetry: Ten Poems to Change Your Life and its emphatic sequel, Ten Poems to Change Your Life Again and Again, along with Ten Poems to Open Your Heart, Ten Poems to Set You Free, Dancing with Joy: 99 Poems and, perhaps most recognizably, Risking Everything: 110 Poems of Love and Revelation.

The various author bios in these volumes suggest that Hous den is quite a provocateur for poets: he “gives recitals of ecsta tic poetry” and “gives a small number of individual coaching sessions by phone on the transformational power of poetry” (his e-mail address follows). A native of Bath, England, Housden has more recently lived in Woodstock, New York, and Marin County, Cal ifornia. His publisher is Harmony Books, which as an imprint sounds more fitting than its parent company, Crown Publishing, and Crown’s parent, Random House. It all fits together very nicely.

In light of this, I don’t know what exactly I was expecting when I turned to Housden’s latest collection, but it’s safe to say that my readerly enthusiasm was not great. I feared that in For Lovers of God Everywhere: Poems of the Christian Mystics, I would encounter a thin selection of poets from the traditional verse cisterns, and I was irritated ahead of schedule about what might pass for mystical.

Well, I hereby eat my words, or at least my less than charitable intimations. For Lovers of God Everywhere is a valuable, fruitful little collection. Some poets included here don’t strike me as primar ily mystical (Aquinas, George Herbert and Gerard Manley Hopkins, for example), but it is safe to say more broadly that this book consists of 98 religious lyrics of various sorts. And even Housden would find the term religious too confining. He focuses instead on poets, whether religious or not, who put their faith in the “more interior, personal experience of God and of existence itself.”

In his introduction, Housden praises the medium of poetry for being able to best capture the “ineffable and the essential,” for being the form of language that is most open to beauty and wisdom and is the easiest to internalize. He sees these poems as generally involved in a “celebration of union” and “true spiritual marriage” and traces this tradition from the Desert Fathers and the monastic orders to persons and groups marginalized throughout church history, such as Marguerite Porete and the Cathars. These writers deserve a broader audience, Housden argues. He’s right, and he’s probably the right person to make that goal achievable—always a tall order in poetry. He also distinguishes between the via positiva and via negativa strains of mystical encounter (Teresa of Ávila on the one hand, and Pseudo-Dionysius or John Tauler on the other).

Although Housden limits himself to figures in the Christian mystical tradition, his universalizing tone welcomes poets of different faiths into this conversation about “our great love songs to God.” He bestows special praise on the influence via translation of Hindu and Sufi mystics who have made contemporary American audiences more open and responsive to their own mystical traditions. In this way, Housden’s collection stands nicely beside Daniel Ladinsky’s Love Poems from God: Twelve Sacred Voices from the East and West, which includes works from Saints Catherine of Siena, Francis of Assisi, Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross, as well as Rumi, Hafiz (whom Ladinsky translates) and Kabir. (Housden himself is the author of a novella titled Chasing Rumi: A Fable About Finding the Heart’s True Desire.)

The range of Christian sources represented in this collection helps to justify the Everywhere in the title. Many of the writers one would expect to find are here—Hildegard of Bingen, Julian of Norwich, John of the Cross, Henry Vaughan, William Blake, Rainer Maria Rilke, T. S. Eliot (a passage from “Little Gidding”), Thomas Merton and Kahlil Gibran. But there is also a generous grouping of contemporary poets, including Denise Levertov, Geoffrey Hill, Mark Jarman, Mary Oliver, R. S. Thomas and Scott Cairns.

Most readers will make a few happy discoveries of poets who are new to them or poets they have only vaguely known. For me, these were the clear paradoxes of Jacopone da Todi, like this one about the soul: “Annihilated, it lives in triumph,” and the creation-praising language of William Everson. Housden provides a paragraph or two of context or a brief meditation on the page opposite each poem, and the appended biographical notes are helpfully detailed. Still, the poems are the thing, and one needs only a single image-driven insight rendered by an unknown poet—for example, the circle in Hadewijch II’s poem “Tighten,” which “is / the world’s things”—to put aside, far aside, a begrudging poet’s reservations and be glad for what is found here.