BookMarks

William Dever invites the reader into the contentious discussion under way in Old Testament studies around issues of method, history and theological claims. Dever, retired from the University of Arizona, is the most influential archaeologist concerned with questions of biblical history and is, he writes, the son of “a fire-breathing fundamentalist preacher” who himself eventually became a “secular humanist,” with seasons as a Christian clergyman and a member of a Reform synagogue.

Dever has woven together two quite different books, each of which is of interest in a different way. On the one hand, Dever has written a rich sourcebook, not really beginning until page 90, on the archaeological discoveries at several sites which contain evidence of life in Palestine in the biblical period. Dever is a master of this material, highly skilled in reading the data and in piecing it together into a coherent narrative account. He pays great attention to the frequency of “high places,” which were rural shrines, and to the many cultic artifacts and the large amount of evidence for cultic practices at those sites. Dever’s interest is not in the “high, normative” religion of Israel that occupied earlier historians and archaeologists, but in the folk religion that, in his view, preoccupied the great majority of the population and was quite distinct from the dominant formal religious practices of the temple that are reflected in the canonical writings.

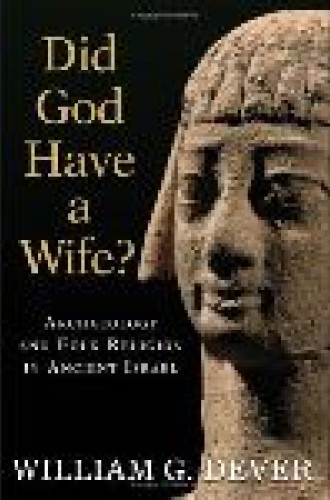

In the midst of this more general tracing of folk religion, Dever focuses particularly on the “Asherah,” a goddess known in the religious environment around Israel and reflected in some parts of the biblical text. The overly dramatic title of Dever’s book concerns the question of whether the textual and archaeological evidence leads to the conclusion that a female god stood alongside Yahweh in the practice of the folk religion of Israel. Dever’s vigorous and enthusiastic answer is yes. Yes, Yahweh had a wife, though that relationship has been largely erased in the biblical text by the work of zealous orthodoxy.

Dever’s dramatic exposé is not as stunning as he would want us to believe, because that same conclusion has been reached by other scholars who lack Dever’s entrepreneurial capacity. In any case, his book is an important attestation that religion in ancient Israel, reflected in the Old Testament text, was variegated and did not conform in any ready way to “church theology,” which reads past much of the evidence. Dever’s critical analysis represents an important and instructive gain for the work of critical scholarship.

There is, however, a second book that permeates the discussion, one that voices Dever’s relentless anger toward and dismissal of many biblical scholars (including myself) who do not measure up to his particular notion of scholarship; that is, they do not pay attention to the data that Dever has peculiarly mustered into a coherent whole. While the point is a valid one, it is scored in a harsh and relentless way that greatly detracts from the argument. The outcome of Dever’s book is that much of current biblical scholarship stands harshly indicted.

My impression is that here speaks the son of a “fire-breathing fundamentalist preacher,” a father who left his son deeply enraged by fideistic approaches that are not sufficiently skeptical of the biblical text and its claims. Dever’s style and rhetoric are intentionally inflammatory and lead to labeling scholars as “oblivious,” “ignorant,” “ideologically driven” and—worst of all—“elitist.” The label elitist functions in powerful ways for Dever as he offers binary lists of the good and the bad that have a nearly Manichean flavor.

In his discussion of Old Testament religion, Dever uses elitist to refer to the urban power structure of priests who imposed formal orthodoxy on the Bible and covered over the richness of folk religion that lived close to the agricultural reality of daily life and kept the predictable routines of creation in its purview. Thus the elitist dimension of Israelite religion in the Old Testament is to be rejected. It is curious that in an “objective, scientific” approach, such a layer of religion should not be studied and understood as a historical datum rather than taken as a cause for polemical dismissal.

In his discussion of contemporary scholarship, Dever uses elitist to refer to scholars who pay too much attention to Old Testament elitist religion and not enough to folk religion, for which Dever offers himself as the champion. Such a dismissive labeling is strange, for I would guess that Dever himself is as elitist in academic circles as those whom he criticizes. Perhaps he imagines that he is the first elitist who has managed to have sympathy for the folk—not allowing that some ancient “elitists” were concerned for widows and orphans, and not imagining that some contemporary “elitists” also care about the feminist agenda that Dever champions. Nor can Dever entertain the thought that some contemporary “elitists” know some of the data he cites and have taken up other tasks. (I have had field experience in the dig at Gezer that Dever himself directed.)

There is no doubt that Dever’s contribution to archaeology (and, through archaeology, to a fresh reading of the text) is compelling and crucial, and throughout the book he calls for dialogue, but his polemical dismissal is not an effective way to evoke dialogue. Dever himself acknowledges that “theology may be a legitimate task of the modern exegete, but it must be kept strictly separate from the task of the historian. It is not the historian’s job to produce data to justify any particular theological option.” Surely no responsible theological interpreter has asked any historian to provide such justification, nor has anyone asked Dever to do so.

Thus Dever leads us back to the old questions of Gabler and Lessing and the “ugly ditch” between faith and history that is still not well crossed by Dever or any of the rest of us. The tone and outcome of the book indicate that Dever’s own emotive presentation is reflective of his early formation as being “either with us or against us.”

This second book of the volume is of interest because it reflects the quarrelsome ferment in the field. It is a ferment that is difficult for Dever, for he must contend simultaneously with elitist fideists and with minimalists who carry skepticism toward the text beyond Dever’s particular brand of legitimate skepticism. With the failure of old paradigms and the lack of new hegemonic ones, the field is open in many directions, most of which Dever rejects.

Readers would do well to disregard Dever’s self-serving polemics and focus on his positive contributions, which are immense. He has provided an important and coherent portrayal of Israelite religion that is marked by variegated faith and practice—a portrayal that simply cannot be ignored.

At the end of the book Dever offers a vigorous advocacy of theological feminism. I wonder how he would relate that advocacy (which I share) to contemporary U.S. folk religion, which has passionate patriarchy and even violent militarism in its repertoire. Beyond the issue of folk religion and elitism in the Old Testament, Dever’s advocacy may be of interest as the elitist Democratic Party tries to interface with folk religion in contemporary U.S. politics. It would be interesting to move from U.S. folk religion back to Dever’s Old Testament folk religion. On that count, folk religion is not so glorious—but that is an issue for another day.

Dever has given us important work to do. It may be that the time is right for the dialogue for which he calls. But it will require a less Manichean tone than Dever offers for that to happen.