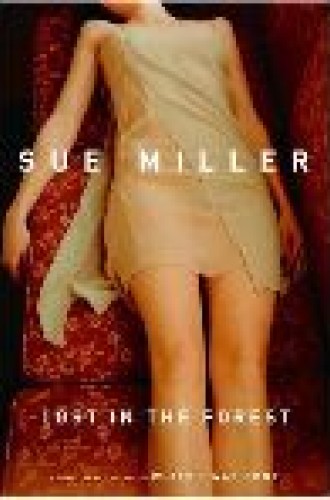

Lost in the Forest

To keep his two-year-old son amused during long family dinners, a father invents a game: he tells the story of a little boy who finds himself in a scary, dangerous place—a cave perhaps, or a witch’s house, or a dark forest. Sometimes the boy rescues himself; sometimes an animal or a kindly human being helps him find his way back home. The whole family takes part in telling the story, passing it on among themselves.

When the father is killed in an accident, his wife and stepdaughter feel lost in the dark forest of grief and confusion. Neither can help the other. The mother struggles to find her own way back to life. The 15-year-old daughter meets a wolf, the husband of her mother’s best friend.

Despite this folkloric underpinning, Sue Miller’s novel is firmly rooted in the everyday reality of family life. Set in California’s Napa Valley during the years when growth in the wineries made land values skyrocket, it’s about finding the work one loves, as well as about the complexities of human relationships. The story centers on a family twice broken—first by divorce, then by death.

Eva has loved both of her husbands. The first, Mark, had a long affair during a year when she was lonely and depressed, struggling to care for their two young daughters. His life after their divorce has been devoted to his passion for his work—managing vineyards—and to a series of casual relationships with women. Eva happily remarries and has a son with her second husband, John. Though Mark sees his daughters regularly, the younger daughter, Daisy, has chosen John as her true father, and John is devoted to her. When John is suddenly killed in an accident, Daisy is as bereft as her mother but has far fewer resources for dealing with her grief and anger.

Though Eva is a central character, Miller focuses in this novel on the importance of fathers. Mark’s thoughts and feelings as he becomes more involved in his children’s and Eva’s lives are a major part of the book.

When Duncan, the husband of Eva’s best friend, is attracted by Daisy’s budding beauty and sets out to seduce her—she is 15, he in his 50s—Daisy lets it happen. Writing about such a relationship is tricky. Political correctness would insist that a girl in such a situation must be a victim, plain and simple, inevitably damaged for life. Miller’s picture is more complex and nuanced. Without in any way romanticizing what happens or making Duncan anything but despicable, she presents this predator also as an unintentional rescuer who helps Daisy to understand something crucial about her life.

Lost in her own grief, Eva is unable to deal with Daisy, even when she becomes aware of some of the lies and deceptions Daisy uses to cover the affair. It’s Mark, the irresponsible father, who steps in to take charge of his daughter, and in keeping her safe and helping her to grow up, he grows up himself.

Miller is masterful at depicting the ways that parents and children, despite their love for one another, can disregard each other—how each can become simply a backdrop for the others’ lives. A moment of realization comes for Eva when she sees her older daughter, Emily, off for a summer in France before the start of college. She realizes that she and the other parents gathered for the orientation have become “the backdrop to the lives about to be changed by the trip. . . . They were the drivers, for God’s sake. The signers of checks. The wage earners. She had a sense, abruptly, of all of them . . . as being simply in the service of the young.”

Daisy has a similar revelation. As she becomes an adult, she realizes that her sense of being lost, intensified by her stepfather’s death, began with her parents’ divorce. She had not understood the power of the “things that hold people together in a sexual union, or push them apart,” and how people’s recklessness with that power can make “others, even their own children, . . . simply not matter to them.” She felt like “collateral damage” in the disaster of her parents’ divorce and her stepfather’s death.

After John’s death, their children become the focus of Mark’s and Eva’s lives. As Mark ends his casual affairs and devotes himself to seeing his daughter safely through adolescence, Eva devotes herself to raising her son and gradually returns to the church. One of the fine things about Miller’s novel is that she makes responsible adulthood look attractive.