Jesus: The prequel

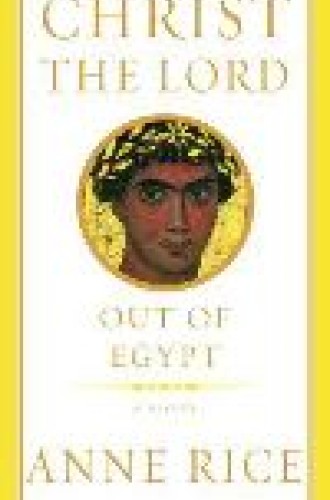

Anne rice, well-known author of many novels about vampires, has returned to the Roman Catholic Church and turned her writing energies to the subject of Jesus. I couldn’t help being intrigued. Perhaps there is a sense in which Rice’s Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt is a response to years of battling with the undead. It’s the horror of death, after all, that Jesus came to overcome. And it’s in the very human physicality of Jesus, in all that is sacrament and sacramental, that evil and death are conquered.

Rice’s book has been publicized as drawing on the best in contemporary biblical scholarship. She has read broadly, and the scholars she refers to in her author’s note are ecumenical in scope.

Readers who do not begin with the confession of Rice’s title, that Christ is the Lord, are unlikely to be convinced of his divinity by the scholarship she marshals. Rice recognizes the disagreements about Jesus in New Testament scholarship and acknowledges her rejection of scholars who would presume against faith. The Jesus she is trying to give us is the Jesus of the Gospels.

Still, we need theology to interpret scripture, and I wish that Rice had read more deeply in theology before she engaged in producing a work of fiction that is also a piece of speculative Christology.

Rice draws a portrait of Jesus as a child. The story opens in Alexandria and carries the reader to Nazareth and to Jerusalem. The novel is largely a character study, but Rice also provides a mystery plot. The boy Jesus is struggling to discover his identity. Mary and Joseph have carefully hidden from him the circumstances of his conception and birth. The deepest secret is also the darkest: the bloodshed escaped by the holy family as they fled to Egypt—Herod’s slaughter of the innocents. And who wouldn’t want to hide from a child the voice of Rachel weeping for her children, refusing to be consoled (Matt. 2:18)? But the child wants to know the truth. It’s an odd sort of mystery, since readers know about the angel’s visit to Mary and have heard the story of the star and the shepherds and the Magi countless times. Rice’s readers know Jesus’ story even as her boy Jesus seeks to learn it.

Above all, Rice has tried to offer a glimpse of a truly human Jesus, a Jesus who is on earth to “breathe and sweat and thirst and sometimes cry.” He is a boy who is afraid, who loves his mother, who must learn the craft of his father. The decision to narrate his childhood and his search for identity is homage to the humanity of the Lord.

In taking up this task, Rice has made an effort to depict a Jewish Jesus. The best aspect of the novel is her success in making real the ordinary rhythms of a family shaped by the covenant, by the law. For readers to whom the observance of the law is foreign, Rice makes it delightfully natural. This Jesus prays the Psalms in the midst of everyday life in a caring family that observes the feasts and quotes the prophets. An anti-Semitic Jesus set over against the law is nowhere to be found. The identity Jesus is seeking is individual, but it is also communal. He is learning what it means to be part of the story of Israel.

This Jesus also grows up in the shadow of bodies on crosses. Rice’s holy land is a land of riots and raiding, of political unease and violent zealotry. She makes it possible to imagine a context in which the Roman Empire is understandably suspicious of any Jew who might claim to be king. Rice helps readers to appreciate the political life of a world in which the child about whom she is writing will die on a cross.

Rice’s effort to open a window into the particular humanity of Jesus is valuable, but it also misses the point in an important way. While trying to portray the Jesus of the Gospels, Rice incorporates legends drawn from gnostic materials about Jesus’ childhood. The book opens with Jesus striking a troublesome playmate dead. His family remembers an incident in which he brought clay birds to life. The choice to use this material defeats the attempt to show us a real human child. This Jesus is magical—more emerging superhero than little boy. This distracts us from the miracle of the incarnation, the truth of God in human frailty. This Jesus is in conflict with the fleshy reality of his own humanity. The seductive gnostic idea that salvation rests in special knowledge rather than in the body of Jesus Christ always needs to be addressed head on. Gnosticism misses the point of the gospel—that God really became human and so saved us real human beings. The incarnate God saves us as the kind of humans we are, weak creatures who die.

The novel tackles a perennial puzzle: How can this Jesus be fully God and fully human? In her portrayal of the boy Jesus, perhaps Rice is attempting to write divinity into a character who is both God and human. But in struggling to understand who Jesus is, Christians have traditionally emphasized the unity of Jesus’ Godness and humanness—in technical parlance, the hypostatic union of the two natures of Christ. The point is not that Jesus is both these things at once but that he is one Lord. The humanity and the divinity of Jesus do not seep into one another, watering each other down. Jesus isn’t a two-headed monster, half God and half man.

Having recognized the first mystery, that Jesus is truly God, Christians have rightly emphasized the wholeness of his humanity. Whatever it takes to be a human being, we find it in Jesus Christ. There is an old idea that Jesus made all the stages of human life holy by going through them himself; presumably, whatever it takes to be a seven-year-old, we would have found it there in the seven-year-old Jesus. In the words of the hymn “Once in Royal David’s City,”

Jesus is our childhood’s pattern;

Day by day, like us He grew;

He was little, weak and helpless,

Tears and smiles like us He knew;

And He feeleth for our sadness,

And He shareth in our gladness.

Jesus is not a human being possessed with supernatural powers. Still less is he a god half-heartedly playacting a human life. He is just Jesus—we can’t divide his divinity and his humanity. We can’t truncate either one. His likeness to us weak people is the source of our salvation. As my daughter put it while coloring a picture of a hugely pregnant Mary, “God is a people too.”

As we emerge from the Christmas season and start the trek toward Lent, it’s not a bad thing to stop and reflect together on the humanity of the child Jesus. At its best, Rice’s book might get us talking about the heart of the mystery of who Jesus is, fully God and fully human—united. This is the sweet mystery of the incarnation, the mystery to which Paul gestures when he tells us that Jesus emptied and humbled himself (Phil. 2). A child animating clay pigeons is not the right stuff. The very real humanity of Jesus is the stuff by which death is conquered, by which all of our vampire nightmares are finally destroyed.