Radical orthodoxy steps into the pulpit

The movement's plucky proponents have been known for their philosophy more than their preaching. Until now.

When John Milbank, Catherine Pickstock, Graham Ward, and friends burst onto the British theological scene with venom and pluck a few decades ago, they demolished their milquetoast liberal predecessors and turned heads even outside theology departments. Few of the arguments of the movement styled as radical orthodoxy were entirely novel. Others before them had said that we should retrieve the church fathers, that the medieval innovation of the univocity of being had birthed such children as secularism and totalitarianism, that Anglicanism could be more Catholic than Rome, that the theology of the gift is more subversive than Foucault and Derrida combined, that the political fruit of orthodox doctrine should be communitarian socialism, and much more. What was new was the mood. Few had said these things with such verve. The Chronicle of Higher Education ran an admiring and slightly nervous piece wondering if they meant it when they said theology should be queen of the sciences again.

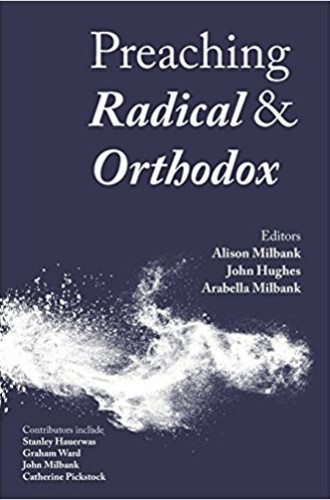

Yet radical orthodoxy seemed unpromising for preaching. As Milbank and friends went scrounging for ever more obscure French philosophers to champion as unwitting witnesses to the profundity of the medieval mass, the fruit for preachers seemed spartan. So Preaching Radical and Orthodox is a very welcome volume. All of the leading luminaries are here—the aforementioned triumvirate plus American fellow traveler Stanley Hauerwas and forerunner Fergus Kerr. The book began as a project of John Hughes, a brilliant academic and priest who died tragically young. If this project is any indication, radical orthodoxy could offer a way of preaching at once new and old that renews the whole church.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Books of sermons can be hit or miss, but there is not a clunker in this volume. They can also be theologically diffuse, but there is remarkable synchronicity here: not uniformity, but coherence. Thomas Aquinas appears as a theologian whose work was for the training of social radicals, doing ministry with the poor. A theology of Mary appears regularly, as does an enormously high doctrine of the Eucharist, celebrated and contemplated and made deeply invitational. One might be forgiven for thinking the sermons Catholic. Fully one third of them—and many of the most memorable ones—are by women.

Alison Milbank is the preacher who appears most often, and Arabella Milbank—a priest in training who is the daughter of Alison and John—appears both as preacher and as an addressee of a wedding homily. Yet, unlike some settings, there is no bashing of tradition here, no apologies for previous misogyny, no special pleading that the church can be nearly as “woke” as the world. Rather, the sermons have a regular and pointed critique of the world, confidently offering the church as a viable alternative.

Most pleasingly to my mind, the sermons engage in an unapologetic reclamation of the legends of the saints: “We still need St. George to point out the dragons of want and greed, and tell us to fight them in society and in our own souls.” The editorial introductions are not attributed to a single author, perhaps because of the state of the manuscript on Hughes’s death, but the introduction to the volume begins with the legend of Mary Magdalene preaching in Marseilles: “Orthodoxy here is not a limit to expel, but an invitation for all to join the Trinitarian encircling life of love given and received.”

Several of the sermons immediately rank among my very favorite on their topic. There is not one but two on angels, whose existence is mysterious, unexplained, dedicated entirely to worship, and delightful. One on the Eucharist describes the first chalice as Christ’s own “veined vessel,” an image from Alison Milbank that I can’t get out of my head.

A sermon on Corpus Christi contrasts the winner of the World Mince Pie Eating Competition, who ingested 11,500 calories in ten minutes, to the very few calories in the wafer, which nevertheless has “within it the raw energy of God.” Another sermon on Mary refers to the highest doctrines about her that even some Roman Catholics wince at—and then argues that nothing happens to her that will not also happen to us: being chosen before birth, made holy, given grace, allowed to feel the world’s pain. Bishop Stephen Conway’s sermon on mental illness burns incandescent: a mentally ill woman points to the crucifix and says, “‘Look at him. He knows. He’s one of us. He’s the friend of Mary Magdalene. And take your medicine.’ She then lapsed back into her mumbling.”

I’m not without quibbles. The sermons have a sort of Anglican tepidness about length. These are so extraordinary they should blow past the typical ten-minute homily that the country club set prefers. I know these preachers are keen to get to the Eucharist, but the church needs catechizing and the world needs evangelizing. Further, I would have loved some observations on how this volume addresses ills and absences in other contemporary approaches to homiletics. But perhaps that is a job for others.

Janet Soskice, a theologian at Cambridge, remarked to me once that a characteristic she shares with peers in Britain like David Ford and Rowan Williams is that they all studied philosophy with seriousness. When many British theologians were toying around with The Myth of God Incarnate and dismissals of bodily resurrection as “conjuring tricks with bones,” Soskice, Ford, and Williams were boning up on Aquinas and Wittgenstein, preparing to teach the theologians who would birth radical orthodoxy. That philosophical bent perhaps explains some of radical orthodoxy’s failings. There’s a sort of showiness about erudition, as if these theologians have to prove themselves smarter than the internal and external critics of the faith. Yet again, if radical orthodoxy makes for preaching like this, may its tribe increase. Let’s all get back to the library—and the sanctuary.