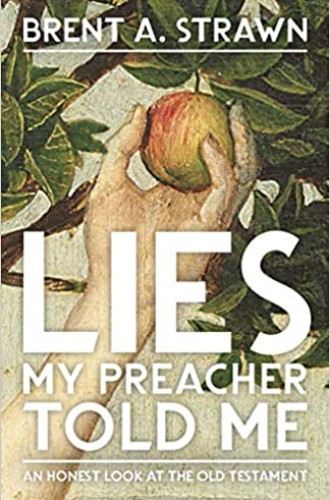

Lies about the Old Testament

Brent Strawn aims to debunk mistruths that come from biblical illiteracy and anti-Semitism.

At least three times in this book, Brent Strawn assures readers that he doesn’t believe that Christian preachers and teachers intentionally tell lies about the Old Testament. But that doesn’t diminish the seriousness of the mistruths that are prevalent in pulpit and pew.

Strawn calls them mistruths rather than lies in part to emphasize how dangerous they can be. “In the case of a lie, the truth simply needs to be brought to light for things to be set right,” he writes. While lies can be set straight with the truth, mistruths are harder to identify. They have deeper (and often unexamined) roots of misinformation or prejudice. “Mistruths are thus far more insidious and intractable than a bald-faced lie,” Strawn explains.

The book covers ten mistruths touching on a variety of topics, including God’s nature, violence in the scriptures, what the law is (and is not), and how the Old Testament relates to Jesus Christ.