Learning to face the doctrine of discovery

I wish I’d had Mark Charles and Soong-Chan Rah’s book when I was in college.

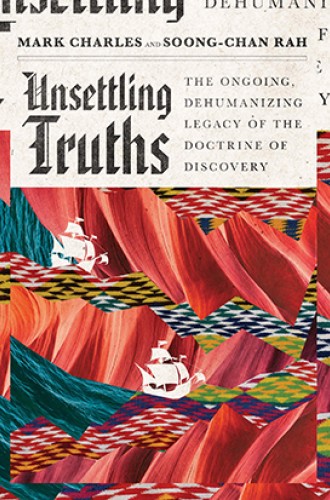

Every spring semester when I was in college, I would pray for another white friend who had headed to the farthest corners of the world to preach the good news of Jesus. Heather was going to Turkey, Steph to Uganda. In the fall, they would come back with stories, trinkets, and pictures of themselves with little black and brown children hanging off their shoulders. In those days, I didn’t know the language of colonialism, American exceptionalism, or white supremacy. The idea of short-term missions made me uncomfortable, but I couldn’t articulate why. I wish I’d had a book like Unsettling Truths.

Evangelical scholars Mark Charles and Soong-Chan Rah, both of whom are people of color, offer a people’s history of the United States rooted in an unapologetic critique of the sins that run through American culture and go back to its founding. They focus on the doctrine of discovery, a theological justification for European exploitation of foreign lands and people that originated in a set of 15th-century papal bulls. Charles and Rah trace the evolution of this theological perversion from the era of Constantine to the white American exceptionalism of the present. They reveal the social dysfunction that results from it, and they name it as a sin that flies in the face of what scripture says about who God is and what our relationship to the world ought to be.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This is the kind of book that sneaks up on you. The first few chapters lay out the theoretical groundwork for the authors’ arguments, and it’s easy to read them at an emotional distance. But the critiques become progressively deeper, and by the book’s midpoint they are visceral. Charles and Rah are not afraid to tear down the idols precious to right- and left-leaning American Christians: Donald Trump, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, the Founding Fathers, and Abraham Lincoln.

Charles and Rah devote two chapters to Lincoln’s abuses toward people of color. In a chapter called “Abraham Lincoln and the Narrative of White Messiahship,” the authors make the case that the 16th president “firmly believed that black lives do not matter.” They cite Lincoln’s language about the inferiority of black people, which he consistently repeated throughout his campaign for the US Senate. They quote his statement in an 1862 letter to Horace Greeley that if he could have found a way to preserve the Union without the freeing of slaves, then he would have done so. They note that the 13th Amendment didn’t abolish slavery but simply moved it to “the jurisdiction of law enforcement officers and the courts,” which would pave the way for financial incentives to mass incarceration.

The next chapter relates the lesser-known story of Lincoln’s role in the genocides of Dakota, Winnebago, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Navajo, and Apache peoples. Lincoln oversaw, encouraged, and implemented numerous actions against indigenous people, including legislation to encourage land seizures (like the Homestead Act), reversals of treaties, forced marches to incarceration sites, and the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. “Despite Abraham Lincoln’s horrific record on the systemic genocide of Native peoples,” the authors note, “he is still regarded as one of the greatest presidents in US history.”

The mythology of Lincoln as an American messiah “who lost his life because of his commitment to the causes of freedom” is a farce, Charles and Rah conclude. “The full record of Abraham Lincoln reveals a president who directly contributed to the genocide of the Native community and perpetuated the dehumanization of the African-American community.”

Near the end of the book, Charles and Rah claim that neither white fragility nor individual racism can fully explain white Christians’ resistance to repairing racial injustice. Another significant factor is “the trauma of white America.” Trauma, the authors explain, isn’t always just individual. It can be transgenerational and communal. Just as people of color experience the historical trauma of centuries of systemic and interpersonal injustice, the perpetrators of these abuses experience what psychologist Rachel MacNair calls “perpetration-induced traumatic stress.” This trauma keeps white people from naming the harm they’ve caused and working toward conciliation.

For Charles and Rah, conciliation involves truth telling. The truth is that “we are not God’s chosen people” and the “United States of America is not, never has been, nor will it ever be a Christian nation.” Charles and Rah suggest that one way to tell this truth is by reciting, as a litany, the names of the 700 tribes of Turtle Island (an indigenous name for North America) whose land was stolen by settlers in the name of the Christian God. The authors include a list of these tribes.

This book will leave many readers feeling not only unsettled but skewered. I can imagine Unsettling Truths provoking tough conversations in a class for first-year seminarians. I can also imagine it being discussed in book groups in church basements or beer halls. This book has something to say to all Christians—whether conservative evangelical, progressive mainline, or something in between—who need to be confronted by the reality of the American empire.