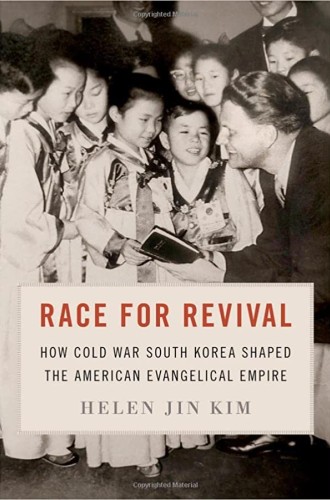

How Christians in Korea helped build American evangelicalism

Helen Jin Kim exhumes the Korean roots of three major evangelical organizations, all present at a 1973 Billy Graham rally in Seoul.

“I’ve never been so cold in all my life,” Billy Graham proclaimed to a crowd of 1.1 million in Seoul in 1973. During those dark days of South Korean military dictatorship, Graham began his sermon by telling the story of his 1952 Christmas visit to Korea during the Korean War—the forgotten “hot war” of the Cold War that consumed some 4 million lives, including those of 40,000 Americans. He invoked the sacrifice of an American soldier who wrapped his body around a North Korean grenade to save the lives of his comrades. Almost simultaneously, thanks to his interpreter Billy Kim, Graham’s words, gestures, and signature cadence became incarnate in Korean.

Helen Jin Kim’s meticulous and ambitious study begins with this vignette. Race for Revival probes the roles played by American soldiers and evangelists and Korean martyrs, orphans, and students in the mid-20th-century emergence of Korean evangelicals amid a resurgence of American evangelicalism. With theoretical sophistication and narrative flair, Kim exhumes the Korean roots of the three major evangelical organizations present at the 1973 rally in Seoul: the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, World Vision, and Campus Crusade for Christ.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The Korean lives that she illuminates are poignant and compelling. Sidelining Graham, Bob Pierce, and Bill Bright, who were historically credited with founding the aforementioned organizations, Kim foregrounds prominent Korean ministers. Her protagonists are Princeton Theological Seminary alumnus Kyung-Chik Han, who founded Korea’s first megachurch; Bob Jones University alumnus Billy Kim, who led the Baptist World Alliance and served as Graham’s translator in Seoul; and Fuller Seminary alumnus Joon Gon Kim, who was known for forgiving the North Koreans who killed his father and his wife during the Korean War.

Although they faced Orientalized racism and were pitted against Black Americans during their student years in the United States, each of these men would eventually chart their own destinies as celebrity evangelists. More tragic was the truncated life of World Vision Korean Orphans Choir inaugural member Kim Sang Yong, nicknamed Peanuts, who died by suicide at the age of 19 to protest what he saw as World Vision’s exploitation of the choir’s members.

Like an evangelist, Helen Kim makes bold claims about her work. She writes that “Race for Revival is the first book to use a transpacific lens to interpret US evangelical history, politics, and race,” adding that she is the first to intertwine the three threads of the Cold War, American evangelicalism, and Korean Christianity. It is true that most studies of Korean religious history have not ventured into the late 20th century and that most studies of modern evangelical organizations have not been transnational. But I wish Kim had included a more explicit conversation about how her scholarship differs from other pioneering works. For instance, historian David Swartz’s Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (2020), which features a chapter on Han’s cofounding of World Vision, is named only in two endnotes.

More than Swartz’s, Kim’s analysis hinges on race. She argues that evangelical is a “polysemic term” with multiple meanings and that the embodiment of evangelical identity in America was forged “by many hands—a multiracial and multinational group of people.” Building on recent scholarship that yokes the rise of modern evangelical America to White supremacy, Kim illustrates convincingly that Koreans’ “racial erasure, integration, and model minoritization” fed the fledgling evangelical empire that subordinated and excluded Black people while intensifying the Cold War.

Kim’s intersectional analyses are often incisive, as when she calls the three evangelical organizations “multinational corporations” that “mimicked the capitalist structure in which the metropole extracts resources from the periphery, without giving credit where credit is due.” Nevertheless, as she attempts to balance the perspective of the historian with the actions of historical figures, there are times when theory seems to eclipse history. For example, she recounts Graham preaching in Seoul that Jesus was not a European but an Asian from the Middle East—yet she also theorizes that “Graham served as the transpacific linchpin that fused the white Jesus, soldier, and evangelist together.”

A more substantive shortcoming of the book is its lopsided treatment of the transpacific history it narrates. Although her account of evangelical America is textured, Kim’s account of modern Korea is less nuanced. In contrast to American evangelicals, whose diversity she sifts painstakingly, she lumps conservative Korean Christians together as “Korean Protestants,” a term that belies heterogeneity. (Korean Presbyterian sub-denominations alone number more than 100.) And while she lifts up liberationist minjung theology on occasion and mentions its influence on some Christian dissidents—including Cho Wha Soon, George Ogle, and Kim Jae Jun, who founded a progressive denomination and seminary—the salience of this theology in the 1970s is missing from Race for Revival.

Kim does elide some significant currents in modern Korean history. Although she mentions American complicity in the colonization of Korea by Japan, she omits Washington’s proposal to Moscow that Korea be partitioned, which was drafted by Dean Rusk (who would later become secretary of state) without consulting a single Korean or expert on Korea. Kim is silent on America’s catastrophic escalation of the Korean War, and her biography of Han does not include his unholy support of the paramilitary Northwest Youth League, which committed atrocities across Korea. The result is a varnished transpacific history that leaves many downtrodden lives in the ashes while buttressing the powers and principalities that ruled Korea and America with blessings from their court ministers.

Despite these shortcomings, I read Kim’s book like an heirloom. My grandfather perished after being wounded in the Korean War, and my father heard Graham in Seoul. My grandfather became a martyr, my father an orphan, and I a student in America. American bombs and bullets have formed countless crosses, and the blood of the innocent cries out from the Philippines, Japan, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Latin America. Race for Revival is a first step toward repentance for our sins in Korea. Kim’s last words include the “call for an end to the unending Korean War, including the cessation of US empire building as well as the use of race to govern others.”

This review was updated on August 4 to more accurately portray the extent of the book's engagement with David Swartz and minjung theology.