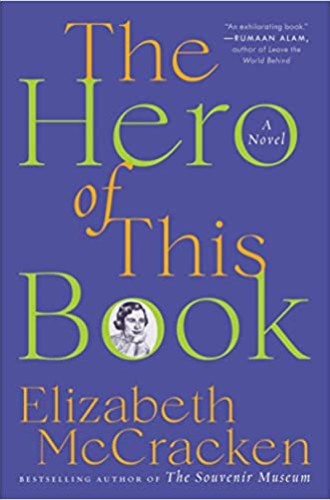

Is The Hero of this Book a novel or a memoir?

In either case, Elizabeth McCracken’s account of losing a mother is wrenching and tender.

Beloved by many readers, Elizabeth McCracken is still best known for her debut novel The Giant’s House, published in 1996. That delightful tale about a librarian and her enormous lover brought McCracken, a librarian, a National Book Award nomination and outsized expectations.

But she did not immediately fulfill them. Instead she became a writers’ writer, quite literally—teaching at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, editing Ann Patchett, and taking up the James A. Michener Chair in Creative Writing at the University of Texas. Five years passed between her first novel and her second; 20 years between her first story collection and the next. Along the way, she lived through the stillbirth of one son and the birth of another, as told in a steely memoir.

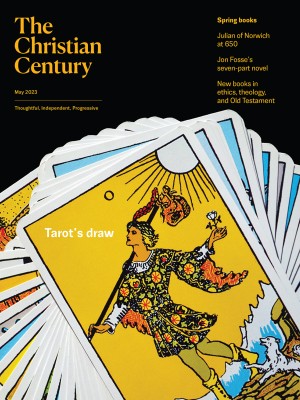

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Lately she has been picking up the pace, publishing four books in the last eight years. Each bears some relation to her own life. Among the recurring themes are lost children, old lore, antiquated talk, vanished places, things one no longer finds in Massachusetts (where she no longer lives), and—perhaps related to these—a kind of spiritual curiosity, even though she has confessed, “My religion is worry.” Why does a boy grow so large that his body fails him? Why does a child die? These are spiritual questions that she meets with just enough humor to carry us from one grave-rubbed page to the next.

So now we have The Hero of This Book, a tricky memoir-or-novel about the loss of her mother. It sure reads like a memoir, although she keeps telling us that it is not one—that her mother distrusted such books, especially when written about family members. To tell the truth about her mother, McCracken insists on calling it a novel and says that she has invented small details, though page by page the pretense seems to fall apart.

If you want to write a memoir without writing a memoir, go ahead and call it something else. Let other people argue about it. Arguing with yourself or the dead will get you nowhere. Imagine a character who can’t profess her love; how do things change if you show the one moment she can?

At first, it might sound like McCracken is talking about her mother. Perhaps she didn’t get enough love in childhood. That would be a familiar story; plenty of writers have penned such complaints. She does admit, “I was mostly a conversational receptacle for my parents. I don’t mean they weren’t interested in me. They loved me, enjoyed my company, but on some fundamental level I’m not sure my mother, anyhow, cared about my inner life.”

But no, this is not that kind of book, and while she writes unsparingly of her mother’s eccentricities, it is with more and more sympathy. The aging, exasperating mom of the early chapters, who hoards newspapers and waffle irons, turns out to be a heroic figure—while gradually we sense that the one who cannot quite profess her love is McCracken herself.

It takes a while for her to acknowledge the depth of her loss. “Grief, as I understood it—grief and I were acquainted—is the kind of loss that sets you on fire as you struggle to put it out.” She professes not to be on fire. (Of her father she says coolly in parenthesis, “I miss him. I’m sorry he doesn’t fit in this book. I’m sorry his last year was unhappy.”) Yet as she regales us with effortlessly funny and apt observations, the prickly judgments that have been her stock-in-trade, it is not hard to see how her parents have made her a writer.

Both McCracken and her mother are small women with large personalities. “Everything makes more sense if you know what my parents looked like. My father was six-foot-three and, for the last forty years of his life, enormous in every dimension, three hundred pounds or more.” (Ah, so that’s where the giant came from.) “My mother was less than five feet tall. . . . My parents were a sight gag.”

McCracken constantly tells her students not to forget their characters’ physical selves, that they are clues to interior lives. If they know what a character is doing with her hands, they might know what she’s doing with her head. Of course, middle age makes us all more aware of the bodies we inhabit—how they are, and are not, us—and McCracken, knocking on the door of 60, is recognizing this. “We’re not our souls, we’re not our bodies,” she writes. “We’re the shimmering border between.”

The drama of this book is all in bodies. At first McCracken notes her mother’s difficulty in getting around, her stiffness, her bad feet. These may sound like problems of old age, until gradually McCracken reveals the seriousness of her mother’s lifelong limitations from cerebral palsy. (Ah, so that’s where the life-threatening medical condition of the first novel came from.) Cerebral palsy, sometimes called “a birth injury,” resonates eerily with the stillbirth of McCracken’s first son. This family has been acquainted with grief, indeed.

Ordinary actions such as climbing stairs have long required them to work together, the daughter’s foot under her mother’s. So for her mother to propose a getaway to London, in spite of obstacles at every turn, is nothing short of heroic. Her mother has come into a little money after her own mother’s death, enough for a plane ticket, and proves herself in many ways an ideal traveling companion even though stairs, theaters, taxis, and even beds present constant challenges. They have the time of their lives. On her own, while her mother rests in a hotel, McCracken climbs 528 steps to the top of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Ten months after her mother’s death, McCracken is back in London, alone and on fire with grief, within hearing distance of the bells of St. Paul’s. She cannot quite accept the consolations of faith. Her own knee has given out and she can no longer climb all those stairs. Everywhere she goes, she finds memories of her mother at her most free-spirited, as well as at her weakest. She recalls,

I took her hand. I did this without permission. My mother was not a hand-holder. I sat by her bed. I said, “I’m sorry this happened to you.” Without permission. I found her dear in this reduced state. I called her honey. I kissed her hello and goodbye. I can’t imagine she approved of any of it.

These little licenses, taken in love, parallel the greater licenses that McCracken takes in writing about her mother for the sake of honoring her. Some of the finest passages she has ever written come as she describes the moral hazards of writing, or what it means for a writer to honor the bonds of family.

Readers may hear in the title an echo of David Copperfield (“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show”). Previously McCracken has shown a Dickensian talent for naming characters; this time around, she gives almost no one a name until the very end, when—in an absurd, tender, strangely moving moment—she names her mother in a footnote. A small thing, and very large.