An American teenager in Slovakia

How a year overseas unraveled and remade Sarah Hinlicky Wilson’s identity

Many of us have vivid memories of high school, when we were figuring out who we are, trying out various versions of ourselves, and figuring out how the adult world works. Some of us kept journals or diaries of those days as we fell in and out of love, reconsidered our religious beliefs, and tried to make sense of what was happening. Few of us go back to those journals and transform them into a book, as Sarah Hinlicky Wilson has done.

Wilson offers here a glimpse into one year of her life as a teenager. She finished high school in upstate New York a year early so she could move overseas with her family. Her father, Lutheran theologian Paul Hinlicky, is of Slovak heritage, and he had been invited to teach at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Bratislava. The Hinlicky family moved to Slovakia a year after its peaceful split with the Czech Republic, known as the Velvet Divorce. Paul and his wife, Ellen, stayed there for six years.

Wilson stayed for just one year, which she writes about in month-by-month chapters. She reconstructs the year largely from written sources, including her journal from her first month in Slovakia, 27 letters she wrote to her high school friend Colleen, and a set of letters her parents wrote to their parents. Much of the book is written in the breathless prose of a teenager, but from time to time she turns a mirror on her teenage self, reflecting as an adult on the process of her self-discovery.

Sarah (which Slovaks hear as dcéra, or daughter) initially saw herself as going home to the old sod, reconnecting with her Slovak roots. She dreamed of becoming a Slovenka, a Slovak woman. But soon she discovered that the label did not match who she was becoming. She came to see herself as an American shaped by her Slovak heritage.

At home in New York, Wilson had been a nerdy girl, complete with braces and glasses. She read voraciously. In the village of Svät´y Jur (St. George) where the family lived, she became someone else: an object of pursuit by Slovak boys. To them, she was very much an Americanka with a hint of Slovakness. She reveled in the attention, such a change from New York. Originally she planned to take a couple of courses at the seminary, but she discovered she wasn’t interested. She did, however, snag a temporary job running the seminary’s library, where she was discovered by still more Slovak boys.

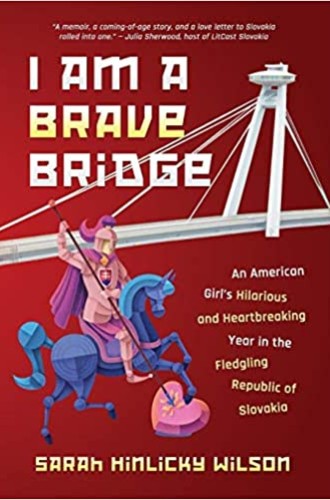

Wilson struggled to learn the Slovak language and its nuances. She heard her parents commit faux pas in Slovak, but as she recounts, she won the prize for the biggest error, which is not appropriate for publication in this magazine. The book’s title, I Am a Brave Bridge, is a translation of the first Slovak sentence she and her brother Will composed: Ja som smelý most. Smelý is an all-purpose Slovak adjective that can also be translated as bold, confident, or undaunted.

Sarah found a home in her church youth group, something she had never experienced at home, where there had been too few youth. In the youth group she found her peers living out their faith, a new experience for her.

At the end of the year, Wilson returned to the United States for college at Lenoir-Rhyne, a Lutheran school in North Carolina. By the time she left Slovakia, her identity could no longer be confined to American or Slovak. She was more than that. The Slovak boys who were chasing her, especially Mišo, realized that they could never live in her world. And she realized that their warm welcome hadn’t made her into a Slovak. Rather, it had unmade her as an American.

Like her father (and her grandfather) before her, Wilson eventually became a pastor and earned a doctorate in theology. After a deeply unsatisfying two years pastoring a Slovak-American congregation in New Jersey, she joined the Institute for Ecumenical Research in Strasbourg, France, specializing in the unlikely combination of Eastern Orthodoxy and Pentecostalism. Today she serves as an associate pastor at a Lutheran Church in Tokyo. She arrived in Japan with her husband and son 25 years to the day after she arrived in Slovakia.

Wilson’s year in Slovakia provided the background for her calling to serve as a bridge between peoples. Her year in Slovakia unmoored her from her Americanness. She explains it this way:

Home as a place and a people is the one thing that will not be restored to me. That’s the way for many, maybe for most, but not for me. My calling is to link them to one another; to translate—however badly; to interpret and connect, at whatever unsettling cost to my comfort and my pride. My place is not the solid ground on either side, but the space in between.

She is indeed a brave bridge.