Holy Saturday in a harrowing time

Christ harrows hell, and nowhere are we beyond the hand that holds that harrow.

A harrow is a spiked implement that is drawn over plowed land to break up clods, tear up weeds, and level the ground for planting. Knowing that bit of agricultural technology gives our figurative use of the adjective harrowing an important layer of meaning. When we speak of a harrowing experience, we mean one that is hair-raising and unnerving, one that disturbs our peace and challenges our sense of security. Whatever in us remains to be broken up and rooted out so that we may be made fertile and fruitful may need to be harrowed. It is not likely to be a comfortable process.

One of the hopes I brought into 2021 was that the harrowing experiences so many of us went through during a year of pandemic and political upheaval might make our common ground ready for new, more fruitful, more equitable ways of doing things: providing education and health care while making institutions more flexible, leadership more agile, and government more responsive and responsible. I hoped the pain we shared and witnessed might help break up the clots of greed and tear out the roots of warmongering triumphalism, break open our hearts, and leave us receptive to seeds of change scattered by a divine hand. Many died in the harrowing months of 2020. Many were pepper sprayed in the streets. Many banners were inscribed with insistent calls for change. That change, when it comes, will have exacted a great cost.

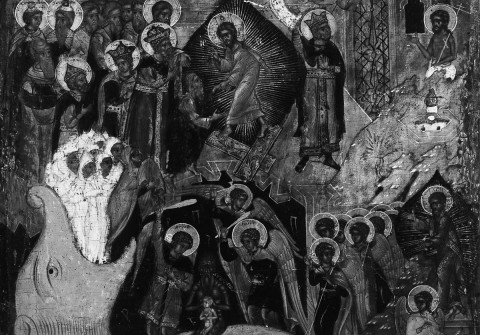

The early church doctrine of the harrowing of hell—the belief that in between his death and resurrection Christ descended to hell and burst its very gates to redeem the dead—is not in the Gospel record. But it makes complete sense given what he came to earth to do: restore our frayed relationship with the source of life, open his arms wide in hard-won forgiveness, and call all people out of darkness into divine light.