The blasphemy of national Christianity

When push comes to shove, for nationalist Christians, ethnicity comes first.

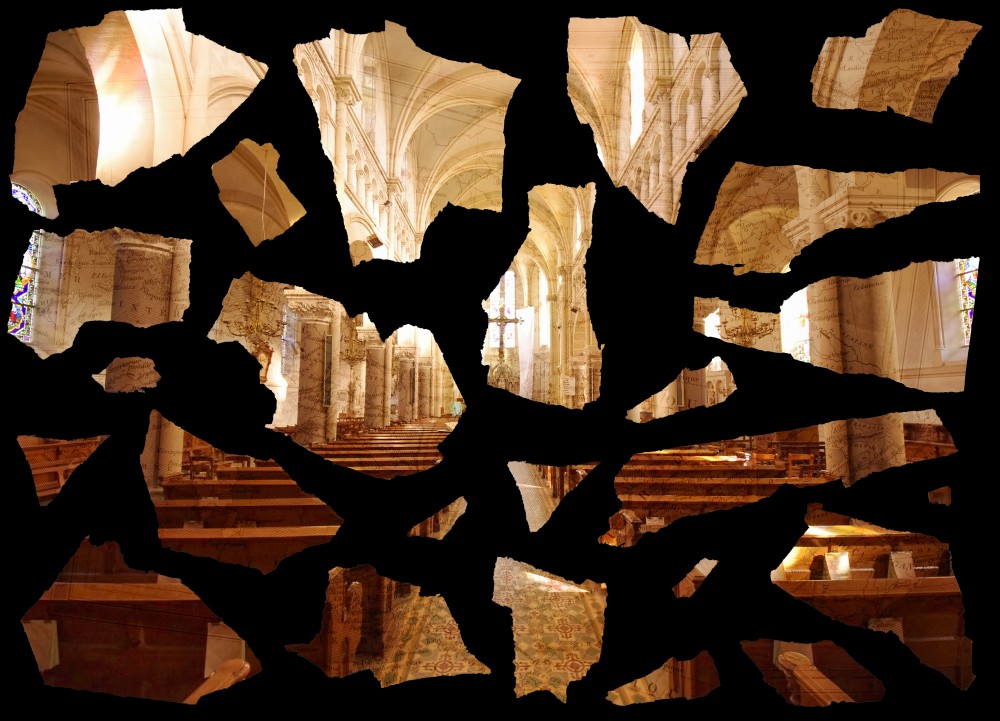

Century illustration

A small ocean of ink has been spilled in the last few years on Christian nationalism, the increasingly successful project by what used to be the fringes of the far-right to prevent the US from ever becoming a secular liberal democracy and instead to cement it as a confessional Christian state. But there’s a flip side to this idea that deserves as much attention. As they work to limit belonging to (White) Christians, Christian nationalists are also hard at work carving up Christian belonging into discrete national (and racial) types. According to this view of things, one is never simply a Christian but is instead an American Christian, or a Palestinian Christian, or a Mexican Christian—and those national differences outrank whatever unity we might have in Christ. This is the flip side to Christian nationalism. Call it national Christianity.

The moral hollowness of national Christianity was on display in July when the Israeli military shelled Holy Family Church, the only Roman Catholic church in Gaza City, killing three people and injuring the parish priest. Joel Berry, the managing editor of the conservative evangelical humor site The Babylon Bee (beloved by Elon Musk, to give you a sense of how funny it is) posted on X that there are “only” 200 professed Catholics in Gaza, and “they all support Hamas.” By virtue of their small number, their foreignness, and their government, the dead and injured Catholics of Gaza were beneath Berry’s concern. Conservative Christian writer Tony Badran, agreeing with Berry, wrote that US protestants need not concern themselves with “ancient communities” in the Middle East, and that such concern is “garbage” and “anti-American.”

Tablet, the Jewish magazine where Badran is news editor, published a defense of Berry that summed up what I’m calling national Christianity. All of the apparent outrage over the church bombing was designed

“to encourage American Christians to identify with Middle Eastern Christians as being fundamentally like themselves, when they are not, and to allow this identification to supersede both their own values and the interests of the political community to which they belong, i.e. the United States of America.”

This is the essence of national Christianity. One might expect Christian nationalists to insist that the values of the nation be subordinated to Christian values, but what they really want is for Christian values to be subordinated to the nation. Christians from different national communities are fundamentally unlike each other, and one’s values and interests as a Christian must be subordinated to the particular values and interests of the nation. In national Christianity, nationality is like a mold into which Christianity is poured. Being an American Christian means having my Christian-ness conditioned by a more fundamental American-ness.

Of course, “nation” here should be understood in a racial sense. Would those who see Palestinian Christians as “fundamentally unlike” American Christians be so quick to complain about a similar identification with British or Canadian Christians?

The idea that the moral demands of Christian faith should be subordinated to the demands of our ethno-national community is laid out explicitly in one of the more influential texts of today’s Christian nationalist movement, Stephen Wolfe’s ponderous The Case for Christian Nationalism. The book argues that the US should be a “Christian nation” in the strongest sense, in which a “Christian prince” shepherds the nation towards its “earthly and heavenly good” by suppressing “false religion” and compelling people to attend church. But not just anyone can belong to Wolfe’s Christian nation. “Nation,” Wolfe says, is a synonym for “ethnicity.” In one section of the book, he defends the idea that a Christian nation can exclude Christians from another nation (read: ethnicity). “Unity in Christ,” he writes, “does not entail or provide unity in earthly particulars.” National and ethnic differences are not overcome but in fact “strengthened” by Christian revelation.

And when push comes to shove, for Wolfe, ethnicity comes first. Reflecting on whether Christians from different nations (read: Christians of different ethnicities) can be part of the same church community, Wolfe declares that “spiritual unity is inadequate for ecclesial unity,” and “civil fellowship is what makes strong church fellowship possible.” It is not only that Christian faith strengthens one’s ethnic ties, but in fact, strong ethnic ties are what make Christian community possible in the first place. More than an argument for a Christian (White) nationalism, Wolfe’s book is an argument for a (White) nationalist Christianity, in which whatever moral claims faith might make are mediated through and subordinated to a prior ethnic identity. At the very end of the book, Wolfe longingly describes a Christian of the future who has discarded the “universalizing concept of man” for a truer “ethno-centric frame.” For such a Christian, “one ethnicity to another would be as dogs are to cats.”

This is blasphemy and must be torn out root and branch.

The categories of nation, race, and gender that we use to dominate and exclude are contingent; these lines have been drawn differently (or not at all) in the past, and they can be drawn differently (or not at all) today. God does not respect whatever petty justifications we give for the narrowness of our hearts. To be baptized into the death and resurrection of Jesus is to be liberated from the imprisoning fiction that another person is fundamentally unlike me and hence lies outside my sphere of concern. The resurrected Jesus is the one who arrives unexpectedly, whose face is glimpsed in the face of a stranger, who vanishes as soon as we think we know who and where he is, who blasts open our sphere of concern and holds it uncomfortably open. It is exactly in the one whom we think is furthest from us, in the one whose suffering and death we think we are allowed to dismiss—the drowned refugee, the child discarded as “collateral damage,” the “unassimilated” immigrant—that we must strain to glimpse the One nearest to us and who is our highest concern.

Today’s national Christians want us to keep our moral responsibilities well within the borders of the kingdoms of this world. We would do well to remember who the prince of this world is.