Inside ‘the new American fascism’

Katherine Stewart explores the strange alliance seeking to impose its antidemocratic vision on the US—one Moms for Liberty meeting at a time.

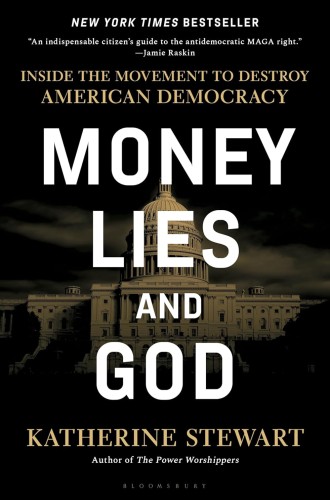

Money, Lies, and God

Inside the Movement to Destroy American Democracy

Katherine Stewart is a veteran chronicler of evangelicals in politics. Her first book examined the Good News Club, an organization that sought to hold Bible studies in public elementary schools to expose children to an evangelical worldview. Her next book, The Power Worshippers, traced the role of evangelical Christians in Donald Trump’s rise. In Money, Lies, and God, she explores the strange alliance seeking to impose an antidemocratic economic and moral vision on the United States.

Stewart argues that this movement, which she calls “the new American fascism,” has multiple factions, including socially conservative evangelical Christians and ultra-wealthy individuals seeking government deregulation and the privatization of public services in order to amass more wealth with which to influence politics. These two groups haven’t always worked together. Evangelical activism used to focus more narrowly on cultural issues such as school prayer, restricting abortion access, and fighting against gay and lesbian rights. But the more attention they gave economic policy, the more wealthy allies they gained—allies who, thanks to runaway inequality, have deeper and deeper pockets. Billionaires—including the Koch brothers, the DeVos family in Michigan, and Richard Uihlen, chair of the Bradley Foundation in Wisconsin—contribute massively to conservative political organizations, and some, such as Betsy DeVos (who is both a billionaire and an evangelical), have been elevated to influential government positions.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Stewart draws on the work of historians to show how the rapid spread of Christian nationalism in recent years has been facilitated by various forces, including a network of sympathetic congregations long primed for conservative political action. The coalition between evangelical Christians and Republican politicians emerged with Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority in the late 1970s. While earlier histories located the movement’s source in the legalization of abortion with Roe v. Wade, newer scholarship traces the coalition to a decision by the federal government to withhold funding from the evangelical Bob Jones University after finding that the school’s policies on interracial dating violated the civil rights of both students and faculty. Historians such as Randall Balmer have demonstrated that a focus on abortion only emerged later, to broaden the alliance’s appeal.

Stewart notes that much of the energy fueling today’s Christian nationalist movement is rooted in evangelical Christians’ cultural anxieties about their waning influence amid cultural shifts, including the legalization of same-sex marriage, the rise of feminism and women’s political power, the changing racial composition of the United Sates, and a visible movement for the rights of transgender people. Conservative organizations have invested decades of time, money, and effort into organizing these anxious Christians in order to mobilize them for conservative political goals.

But Money, Lies, and God also makes it clear that Christian nationalism is not precisely Christian. It includes people who hold various religious commitments and policy agendas. To equate “White evangelical” with “Christian nationalist” is to obscure a deeper truth: Christian nationalism is not a religious movement at all. Rather, it is a political ideology rooted in a mindset that Stewart says consists of catastrophism, a persecution complex, identitarianism, and an authoritarian reflex.

The links between the various wings of the movement are not always obvious to outside observers, as Stewart shows. For example, Moms for Liberty claims to be a grassroots organization, but it was cofounded by the wife of the former chairman of the Republican Party of Florida. The movement seeks to establish charter schools that respect “parents’ rights,” but Stewart reveals the involvement of a for-profit charter school operator from Florida (where over half of the charter schools are run by for-profit companies) and notes that the heiress to the Publix grocery store chain has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to the organization. The hidden links between so-called grassroots movements, big businesses, and ultra-wealthy individuals are what gives these movements so much power.

Stewart vividly describes gatherings of groups that are part of the emerging authoritarian movement. At a desert rally sponsored by ReAwaken America, she huddles in air-conditioned outdoor tents with people who have traveled across the country in their RVs to hear speeches by Michael Flynn, Roseanne Barr, anti-vaxxers, and QAnon conspiracists. At a Moms for Liberty conference in Philadelphia, she meets White women in expensive outfits who are being trained to scour their school libraries for books with “homosexual themes” and to run for their local school boards. “I dip into the spread of fancy appetizers that greets us at the Museum of the American Revolution, and it is delicious,” she writes. “I have been attending right-wing conferences for about fifteen years, and this one is among the most lavish.”

Stewart insightfully identifies the anxieties that lead everyday Americans to embrace what is clearly an antidemocratic and authoritarian political movement. She also provides a glimpse into the movement’s intellectual centers, notably the Claremont Institute in California, whose affiliate John Eastman is credited with what many see as a crackpot legal theory that would have allowed Trump to stay in power after the 2020 election.

Money, Lies, and God was written before the 2024 election. It may seem even more relevant now than it did when it was written, given the Trump administration’s crafting of policies that fit the Christian nationalist agenda, including attacks on transgender people, the deportation of immigrants who were in the United States legally, and the gutting of the Department of Education, which has long been a target of people seeking to move tax dollars to private schools. But Stewart makes it clear that the elite forces she exposes are nothing new. The political impulses that have worked to create the current state of fear-based politics in the United States are part of “a massive, decades-long, farsighted investment in the people and infrastructure of an antidemocratic shadow party, and this investment has deposited its toxic fruit in courthouses and state capitols across the country.” What is newer is the staggering amount of money behind the evangelical movement, from billionaires who are ever more willing to bankroll conservative social policies in return for evangelical votes for deregulation and lower estate taxes.

This book will unsettle many readers, which is a testament to the care and power with which it is written. Still, Stewart ends on a note of hope for those who oppose the current authoritarian movement. She points out that the current conservative coalition has points of disagreement: a libertarian billionaire who wants low taxes may not be opposed to gay marriage, while a Catholic proponent of public funding for religious schools might oppose cuts to Medicare and Medicaid. She reminds readers that the majority of American citizens don’t embrace the moral and economic vision of the current presidential administration. We can counter its influence, she suggests, if we organize and vote.