The fish wars

The Boldt Decision wasn’t just about salmon. It was about broken treaties and tribal sovereignty.

Treaty Justice

The Northwest Tribes, the Boldt Decision, and the Recognition of Fishing Rights

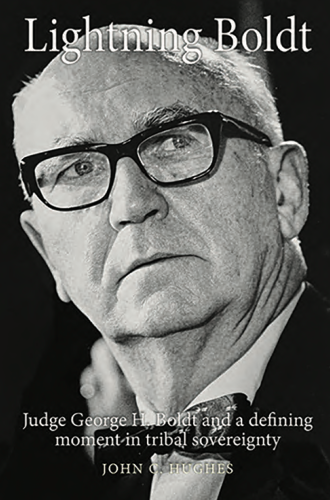

Lightning Boldt

Boldt and a Defining Moment in Tribal Sovereignty

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of one of the most significant court cases in the long and troubled relationship between the United States government, Indian tribes, and the states. In a sweeping decision that was comparable in impact to Brown v. Board of Education, federal judge George H. Boldt decided for a group of 20 tribes and against the State of Washington. Some 130 years earlier, in the winter of 1854 and 1855, Indian fishing rights had been reserved by the tribes in treaties in which Washington territorial governor Isaac I. Stevens acted on behalf of the federal government. In Boldt’s 1974 decision, he declared that those treaties were still “the supreme law of the land,” as Article VI of the Constitution states. He recognized the tribes as sovereigns in the treaty negotiations and stated that their treaty-guaranteed fishing rights could therefore not be impinged upon nor abrogated by the State of Washington. The Boldt Decision, as it came to be known, was upheld by the US Supreme Court five years later in a 9–0 decision.

Two recent books illuminate the history and background of the Boldt Decision. Charles Wilkinson, who died last year, was a widely respected legal historian familiar with federal Indian law and the ongoing struggle of Northwest tribes to assert their treaty-reserved fishing rights. He was also familiar with many of the combatants in the “fish wars” of the 1970s and ’80s that took place on the rivers of western Washington and included the United States v. Washington case tried in Boldt’s federal courtroom in Tacoma. Wilkinson previously wrote about this ongoing conflict in Messages from Frank’s Landing (2000) and Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations (2005). His new book, Treaty Justice, provides a compelling description of the case, including the complex history that led up to it and the surprising aftermath that continues to affect the lives of Native and non-Native northwesterners today.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Wilkinson’s book—completed shortly before his death in 2023—is a response to a 2013 request from Billy Frank Jr. (Nisqually), a major proponent of Indian fishing rights, for a readable and accessible history of the Boldt Decision for both tribal members and the general public. The result is a definitive history that is unlikely to become outdated.

In the tribes’ suit against state efforts to regulate their fishing, Boldt clearly recognized for the first time that tribal sovereignty—guaranteed in the treaties—severely limited the State of Washington’s ability to regulate Indian fishing on and off reservation. He also held that the tribes were entitled to up to half of the available fish and set them on a path to becoming comanagers with the state and the federal government of their treaty-guaranteed resources, especially salmon, which are an icon and life force of the region. Previous courts had recognized salmon “as not much less necessary to the existence of the Indians than the atmosphere that they breathed.”

Treaty Justice is based on Wilkinson’s familiarity with the historical record of treaty negotiations as well as previous court cases in which the Indians attempted to assert what they believed Stevens had promised them. Wilkinson also familiarizes readers with the anthropological evidence upon which Boldt based much of his decision in favor of the tribes.

John C. Hughes is a former newspaper reporter and editor who currently serves as the chief historian for the Washington secretary of state. Having lived through and reported on the events that led up to the Boldt Decision and its aftermath, Hughes offers a biography of the judge behind the decision. Without neglecting the historical or legal aspects of the case, Lightning Boldt provides a critical description of the remarkable person who decided in the tribes’ favor.

Born in Chicago and raised in rural Montana, Boldt graduated from law school, moved to Seattle, and worked in private practice before serving in Burma during the Second World War. The war was crucial to Boldt’s formation, especially his outrage at the internment of US citizens of Japanese descent. In a letter to his wife, Eloise, he vowed to change his attitude toward the Japanese citizens. “I am ashamed to say that before I left Seattle my ideas on this matter were utterly wrong, misguided and cruel. I did not know what I was talking about, but I intend to make up for that in any and every way when I can get back to civil life.”

Boldt was appointed to the federal bench by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the summer of 1953. In an ironic twist, the other candidate for the position was Tacoma congressman Thor Tollefson, who later became the Washington State fisheries director at the time of the case.

Hughes describes how, during the trial, Boldt sat with rapt attention as Indigenous elders described their understanding of the treaties’ promises regarding the right of the Indians to fish “at all usual and accustomed grounds . . . in common with all the citizens of the territory.” Many of them had recent ancestors who were present when the treaties were signed.

To create a context for understanding the treaties as the Indians understood them, Boldt relied on the testimony of anthropologist Barbara Lane. At the time, Lane was the most knowledgeable person in the country about the history and cultural practices of Northwest tribes. Her testimony, along with that of the Native witnesses, proved compelling.

The impact of the Boldt Decision was widespread. Commercial fishermen suddenly were forced to share their catches with tribal fishermen. Sports anglers, whose license fees supported the departments of fisheries and game, suddenly found themselves in a similar position. The state was forced to recognize the tribes as comanagers of a resource they could no longer regulate. The fallout was swift and fierce. Boldt was vilified and hung in effigy. State officials vowed to appeal the decision and, in some cases, refused to honor the court order. In its ruling upholding the Boldt Decision, the Supreme Court offered what Wilkinson calls a dramatic pronouncement of a kind it rarely makes: “Except for some desegregation cases, the district court has faced the most concerted official and private efforts to frustrate a decree of a federal court in this century.” Years of acrimony and strife followed.

But the story doesn’t end there. In the aftermath of the decision and continuing conflict, two of the major combatants—Frank, the fishing rights advocate, who’d been arrested and had his gear confiscated by the state more than 30 times while trying to exercise his treaty-guaranteed fishing rights, and Bill Wilkerson, director of fisheries for the State of Washington—realized it made little sense to continue fighting over a rapidly diminishing salmon population. Wilkerson and Governor John Spellman agreed that “what was needed was to end the fish war.” Frank later put it this way to Wilkerson:

We’re the advocates for the salmon, the birds, the water. We’re advocates for the food chain. We’re an advocate for all of society. Tell them about our life, and how we [Indians] live with the land, and how they’re our neighbors. And how you have to respect your neighbors and work with your neighbors.

Wilkinson concludes that the Boldt Decision and its aftermath demonstrate an instance where, despite controversy and conflict, “the rule of law held, not just in the courts, but in Congress and the general public as well.” Our country is currently in desperate need of such examples.