A diary of small apocalypses

In Charlotte Wood’s novel, an atheist is driven by climate despair to an isolated convent, where she grapples with layers of grief.

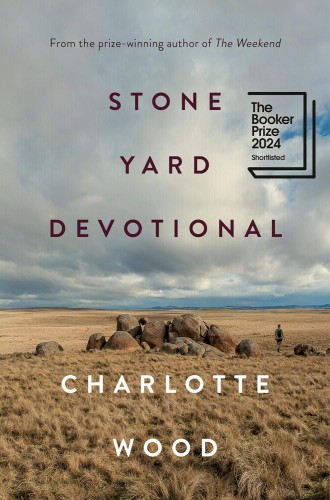

Stone Yard Devotional

A Novel

“Do you have to believe in God to join a religious order?” the unnamed narrator of Stone Yard Devotional muses. “Nobody has ever asked me, specifically, about belief. And anyway, I haven’t ever joined. Not really.”

She has lost her faith. She was never a devout Catholic, though the novel opens with her first visit to the isolated convent where she eventually will come to live. Rather, the calamity that brings the narrator to the convent, and then back to her hometown in rural Australia, is her loss of hope in the future. After decades of working for environmental causes alongside her husband, she has lost her faith that our damaged world will continue on or that her efforts have made a difference. It is this loss that drives her to the convent, despite having left religion behind long ago.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The people in her former life have no room for her grief. Her husband blames her for their separation; her coworkers respond with contempt; her best friend writes her scathing letters and encourages other people to do so as well. Her despair isn’t meant to hurt her friends; indeed, she agrees that despair is a noxious presence in a soul and in a community: “I read somewhere that Catholics think despair is the unforgivable sin. I think they are right; it’s malign, it bleeds and spreads. Once gone, I don’t know that real hope or faith—are they the same?—can ever return.”

But even at the convent, her climate grief spreads, turning her gaze to a catalog of other griefs, both large and small. One large grief: the death of her mother, which she has never really recovered from. Smaller griefs: the mice who nibble the corpse of a dove in the convent chapel; the plastic wrappings around the snacks in her guest room; her own petty annoyances with the sisters.

I read most of Stone Yard Devotional in a church courtyard in downtown Asheville, North Carolina, six months after Hurricane Helene devastated the city. As I read, friends in my hometown in Texas were without power from the storms that stretched across the country from the Gulf of Mexico to Connecticut. Deeper in the North Carolina mountains, a family friend who died in the Helene flooding was being interred in her family’s graveyard. Grief—even despair—was not far away.

Yet it was easy to be absorbed by Charlotte Wood’s spare, straightforward prose. The narrator shies away from metaphor and hyperbole; the diary entries, arranged into spacious vignettes on the page, chronicle a woman engaged in a serious reexamination of her life. Although she remains an atheist, the novel is interested in the ways that the repetitive work of religious community forms—and perhaps malforms—one person’s life.

Over the course of the novel, climate events are small apocalypses: they reveal, they uncover. A historic flood in Thailand uproots an old tree in a churchyard, revealing the bones of a murdered nun who left the convent decades earlier. The global COVID-19 pandemic makes the return of the bones nearly impossible—until Sister Helen Parry, a climate activist and former classmate of the narrator, agrees to accompany the remains to the convent and disrupts their familiar routines. A long drought in the region brings a plague of mice to the convent, forcing the sisters (and the narrator, now a permanent resident although not a nun) into all-out warfare against the rodents. In interviews, Wood calls these events “visitations.” The visitations destabilize the convent. They force the sisters to change their routines. They command attention.

Wood’s interest in the possibilities of attention reminded me of Simone Weil’s writing on prayer. So I was, of course, delighted when the narrator quotes Weil on just this topic. “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer,” Weil writes. “It presupposes faith and love. Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer. If we turn our mind toward the good, it is impossible that little by little the whole soul will not be attracted thereto in spite of itself.” The narrator wants to believe this is true but doesn’t quite. Yet the quote seems to me to be the hinge point of the novel: the moment when the narrator turns from unmitigated despair to something else, something that might not be faith but is adjacent to it. She is able to focus her attention again, an action that despair had taken from her. She is able to act at all.

Stone Yard Devotional reshaped my own attention for the span of a few hours. The final, poignant image of one character faithfully tending to her compost bin made me contemplate what is, ultimately, the bedrock of my belief. What do I believe our damaged world will amount to? Sitting in that Asheville garden, I felt my mind being turned toward the good.