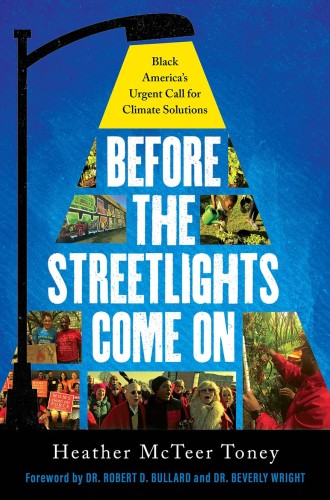

Fighting climate change with Black soul power

Heather McTeer Toney’s masterful weaving of storytelling, history, hope, and scientific truth is for Black people, White allies, and everyone.

Before the Streetlights Come On

Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions

“How in the world are Black folks supposed to talk about climate change when we have other pressing issues to deal with? How and better yet, why?” Heather McTeer Toney’s opening questions cut to the chase: How is climate change relevant to Black Americans who already face daily challenges to

survival?

In a nation where every Black family knows the stakes of getting home before the streetlights come on, this is a legitimate question. McTeer Toney says getting home beforehand is a matter of personal safety (“Your mama didn’t raise no fool”), communal responsibility (“When one had to be in, all had to be in. I am my sister’s, brother’s, cousin’s, next-door neighbor’s, and church member’s keeper”), and urgency (“Hurry up, we ain’t got all day!”).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The phrase “before the streetlights come on” becomes McTeer Toney’s central theme for taking action on climate change before it’s too late. Through it, she speaks directly to the Black community she hopes to rally and empower for climate action leadership. She offers statistics showing that Black Americans and other marginalized people are disproportionately affected by climate change. Their communities have been historically redlined and are still subject to the close proximity of polluting industries: Black people are 75 percent more likely than White people to live in these areas, now called fenceline communities. Black Americans breathe 40 percent dirtier air than White Americans, and their neighborhoods are often both food deserts, lacking fresh produce, and concrete jungles, lacking oxygen-generating trees and cooling green space. McTeer Toney makes a strong case that while White agnostics have been at the center of the climate change movement, Black folks have traditionally held a closer relationship with the earth through agricultural and ancestral wisdom. Furthermore, she argues, since Black folks are the recipients of environmental problems, who better to lead the charge?

What follows is a masterful weaving of storytelling, history, hope, and scientific truth that offers a deep dive into the intersectionality between climate change and racial justice. To be clear: this book is for Black people; this book is for White allies; this book is for everyone. McTeer Toney’s combination of personal narrative, social justice commentary, and practical wisdom steers all readers into a deeper understanding of the relationship between racism and environmental harm, illuminating the ways they intersect to the detriment of our collective well-being.

Although this deep dive is serious and emits a cry of urgency, McTeer Toney’s playful demeanor and laugh-out-loud metaphors make me feel like I can show up for the plunge in my simple snorkel gear—goggles, fins, maybe even a rubber duck inflatable. (Have you ever compared trapped greenhouse gasses to your cousin farting and trapping you underneath the blanket?) She’s a teacher at heart. Her passion lies in making the ins and outs of climate science and social justice issues attainable, understandable, and actionable.

Each chapter addresses an issue in depth and is followed by a mini glossary entitled “Make It Make Sense,” which defines terms such as global warming and carbon capture/sequestration. The writing effortlessly provides newbies and veterans equal footing in the climate conversation, without an ounce of pretentiousness or shaming. We’re given creative examples of our possible present and future, such as a seaweed diet that might save the planet from the interminable methane gasses cows produce. (It’s a seaweed diet for cows, so you can still enjoy your occasional steak!) Consistently, McTeer Toney steers away from the guilt trips we often hear. Yes, individuals can make a difference, but let’s take on the corporations and systemic racism that are the root cause of our trouble. Flint, Michigan, wouldn’t need to buy plastic bottles of water if it were granted the essential right of clean, lead-free drinking water. Each chapter ends with a call to action that lists tangible ways to get involved now, before it’s too late.

And when will it be too late? I started reading this book during a family road trip from Wisconsin to North Carolina. As we drove south, the temperature climbed to 90, then 98, then 102. When we landed in a hotel room with a broken air conditioner unit, the thermostat in the room read 88 degrees, and it was stifling—thick and unbearable. We tried to imagine living in that kind of heat and humidity all summer long. We drove through fenceline communities on the edge of oil industries in Kentucky, with smokestacks billowing into the formerly blue sky. My five-year-old was dismayed: “Why are they doing that? They don’t love the earth!” We approached mountainous North Carolina with awe for its beauty, not knowing we were in a state where the streetlights were about to come on. Soon after, Hurricane Helene caused extreme flooding throughout the Appalachians. Hardly a moment later, Hurricane Milton was raging.

We are witnessing in real time the acceleration of extreme weather due to climate change. Remember the winter storms in Houston? Remember the climate scientist who broke down weeping on national television? We don’t know how much time we have before the streetlights come on for good.

So, for everyone who has stood on the sidelines wringing their hands or stood in the center just trying to survive, for everyone wanting to jump into action for climate justice and racial justice without the know-how, McTeer Toney delivers a two-for-one banger. Her humor and down-to-earth nature build trust with readers, inspiring us to grab our snorkels and dive in. Along the way, she emphasizes the priority of looking out for each other—a priority that is painfully missing in our world these days. In the end, we see that there is no other determination than our vast interconnectedness: earth, air, water, humankind, all creation. And a hope that Black soul power will lead us.