Jesus the fallible

Why would we want a higher doctrine of scripture than we have of Jesus?

Photo: Jens Domschky / iStock / Getty

Jesus may have been an excellent carpenter. Or maybe he wasn’t. It’s possible that he made perfectly level tables but wobbly chairs. Or, if he was a stone mason, which the Greek word translated as “carpenter” in Mark 6:3 allows for, he may have chiseled stone with great precision but laid slightly crooked walls. We can’t know these details of his early life, of course. But let’s turn to the art world to broaden our perspective.

In London’s Tate Britain gallery resides one of John Everett Millais’s most famous paintings, Christ in the House of His Parents. Millais (1829–1896) depicts Joseph in his woodshop, leaning over his rough-hewn workbench to comfort his son with the touch of his hand. Wood shavings cover the floor. Jesus centers the work, a red-headed, elementary-school-age kid bleeding from a cut on his left hand. The blood, the result of a failed attempt to remove a nail from a board, drips onto his bare foot. His attentive mother kneels beside him tenderly. John the Baptist, who looks all of 10 or 11 years old himself, carries a basin of water toward Jesus for washing the wound. The injury clearly foreshadows crucifixion, just as the water bowl prefigures baptism.

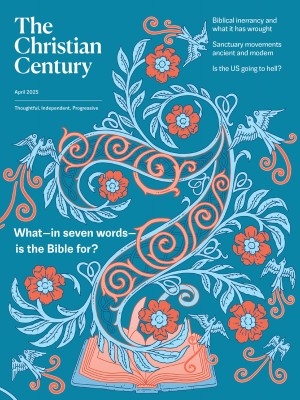

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Millais’s painting highlights Jesus’ human nature. To be human is to be fallible. It means making mistakes, stubbing one’s toe, misspelling a word, or slicing one’s hand. Having metal pincers slip while trying to remove a nail doesn’t constitute moral error on the part of Jesus. It’s not an accident that affects his holiness or taints his sinlessness; it simply wounds him. Learning by trial and error is part of human development. And, in Jesus’ case, we know he grew in stature and wisdom (Luke 2:52). Because he was fully human, he was also fallible. To suggest otherwise—that he never could’ve made a mistake in carpentry or masonry—is to cozy up to the heresy of Docetism. Docetism denies the full and true humanity of Jesus, believing instead that he only seemed human, that his human form was an illusion.

I raise this subject of the fallibility of Jesus in light of the doctrine of the infallibility of scripture, to which many Christians subscribe. When several hundred evangelicals gathered in Chicago in 1978 to draft their now famous statement on biblical inerrancy and infallibility, their stated aim was to secure the certainty of scripture’s authority from “unstable relativism.” Biblical inerrancy, their document articulates, is that “quality of being free from all falsehood and mistake … without error or fault in all its teachings.”

Are we sure we want a higher doctrine of scripture than we have of Jesus? That he is fallible but that scripture, penned by humans and inspired by God, is not? That Jesus would be fully divine and fully human, but scripture only fully divine? That when God orders the mass slaughter of Canaanites and Amalekites (Deut. 20, 1 Sam. 15), we must accept this as unchallengeably and authoritatively of the mouth of God? All because the biblical text is inerrant?

I wonder how different the shape of biblical interpretation might be for all of us—literalists and every other tradition—if when assessing the value of scripture we spent less energy revering the concept of authority and more energy celebrating the idea of gift. A gift brings surprise when it’s opened. Every gift has the potential to bring love, foster humility, and usher in generosity. There’s always a giver attached. A gift may be useful (uti) or enjoyed (frui), depending on its particulars. And it stands to reason that wielding a biblical passage like a hammer to prove the unrighteousness of another person doesn’t exactly bespeak gift.

If only we could follow and treasure scripture simply for its delivery of the truth of the good news of God, which is nothing short of a gift.