Rose Macaulay was ahead of her time

In Crewe Train, the neglected Anglo-Catholic novelist tells the story of a woman who resolutely does not fit in.

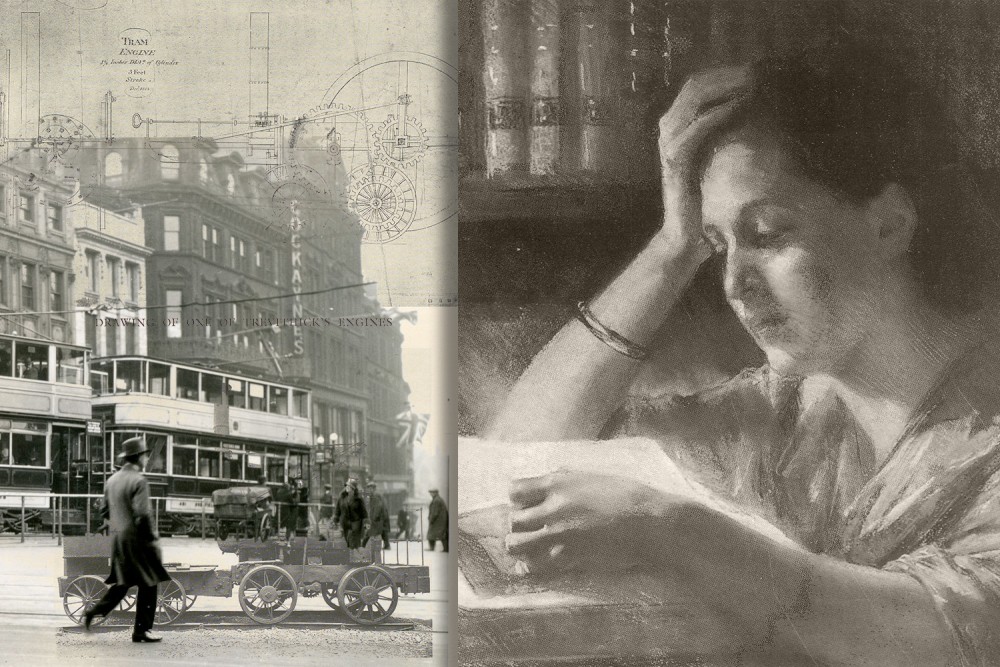

Source images: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons | Image sources: Polona Digital Library / Stockholm Transport Museum / Albert Edelfeldt (All public domain)

Rose Macaulay (1881–1958) was an English novelist with views that were mystical and (eventually) Anglo-Catholic, and moreover passionately feminist. A prolific and once very popular writer who addressed wildly diverse, often daring topics, many of her novels deserve rereading. But one brilliant book in particular clamors for rediscovery.

For many years, Macaulay was chiefly known for one comic novel, the delicious Middle Eastern travelogue The Towers of Trebizond (1956). It is cherished for its memorable opening lines: “‘Take my camel, dear,’ said my aunt Dot, as she climbed down from this animal on her return from High Mass.” As so often in her writing, Macaulay uses satire and wild comedy to make deadly serious points, and the book presents a troubling case study of the clash between religious obligation and adulterous sexual desire.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Readers long knew her as the author of that one book, and only recently has there been renewed interest in others among her more than 20 novels. These include What Not: A Prophetic Comedy, published and suppressed in 1918 and then formally reissued the following year, which envisages a eugenically controlled future Britain. Under the Ministry of Brains, all citizens have their life chances and mating opportunities wholly controlled by official assessments of their intelligence, which are graded alphabetically. Aldous Huxley thought enough of the book to plunder it wholesale in Brave New World.

With The Towers of Trebizond in mind, you might expect high comedy when you turn to Crewe Train (1926), which takes its title from a rollicking music hall ditty about a woman aboard the wrong train. The publisher presents the book as “a devastating—and very funny—social commentary,” suggesting a kind of Jazz Age Candide. Devastating, yes, but “funny” is not the best adjective for what I would call a perceptive and truly oppressive story of damnation. Arguably, it is one of the best of its kind in modern fiction.

As the title suggests, Crewe Train tells the story of a young woman who finds herself absolutely on the wrong track, being led to a destination far removed from anything she wants. Denham Dobie has been raised in remote Andorra by her father, a reclusive Anglican cleric. When he dies, her relatives come to bring her back to London, where she can be properly introduced into polite society. Here, they think, she can be civilized and made normal. Surely, they expect, this will just be a matter of smoothing off some rough edges and immersing her in suitable pleasant company.

The problem is that Denham is not just unpolished. By the conventional standards of the day, she is practically feral. She is called a “Philistine,” even a “Barbarian”—a complete outsider. She is seen above all as “unsociable,” a uniquely harsh judgment in a society that counts pleasant sociability above all other virtues in a woman.

Reading Crewe Train today, we are very tempted to apply contemporary psychological labels. Denham has no sense whatever of social rules. Her repeated failure to understand what others are feeling or thinking makes her seem inappropriate, blunt, or downright rude, although she absolutely lacks malice. She has no sense of social nuance or irony, and she takes remarks painfully literally. At this point we might well remark that Denham fulfills basically every one of the classic symptoms of adult autistic behavior and that Macaulay arguably is offering an acute account of something very much like this condition a decade or so before mainstream scholarship would formulate its own official lists of symptoms.

Armchair diagnosis is always a risky business, even with fictional characters, and in this case it is not necessary. For Macaulay, Denham’s central problem is her loathing and active fear of social interactions, which need not be rooted in any kind of medicalized diagnosis. Such situations make Denham deeply uncomfortable, and she hates intrusions on her space and the routines of her life. Her preference for solitude, for her own company, leads to calamitous interactions with characters who make every heavy-handed blunder they can in trying to bring Denham “out of her shell,” as they put it.

As readers, we see just how unwittingly cruel all these well-meant interventions are. No, Denham does not want to be introduced constantly to parties, reading groups, and social gatherings, but nobody understands her resistance, much less respects it. She glories in her discovery of a spectacular coastal site where she can actually be alone, until her dreadful mother-in-law chooses to reveal its location in a press interview and makes it a tourist destination. Surely, her mother-in-law thinks, Denham will enjoy the company and attention! What normal person wouldn’t? For Denham, these interventions almost literally constitute mental torture.

I cannot avoid here offering something of a spoiler, but not one that is terribly surprising in the context. Denham’s sympathetic (though largely uncomprehending) husband promises they will move to a new home in the distant suburbs, where she can roam to her heart’s content in relatively unspoiled nature and lead a solitary lifestyle. At last she has a glimmer of hope. But her relatives make no secret of their satisfaction at the move, which they hope will accomplish all their plans for Denham Dobie. As they well know, this new suburb is not only fast expanding but also has a very active “smart set” of fashionable young people, who will keep Denham in a never-ending whirl of parties, games, sports, theatricals, and conversation. We realize the (for her) hellish fate that Denham faces, until her dying day.

I repeatedly find myself thinking back to that vision of Denham’s grim future with sympathy, anger, and frustration. Try as I might, I can’t resist citing Sartre’s dictum, that hell really is other people.

Crewe Train is a pioneering study of women who refused to play the social game.