What does it mean to be a woman who doesn’t want children?

Erin Lane challenges maternal exceptionalism and its myths.

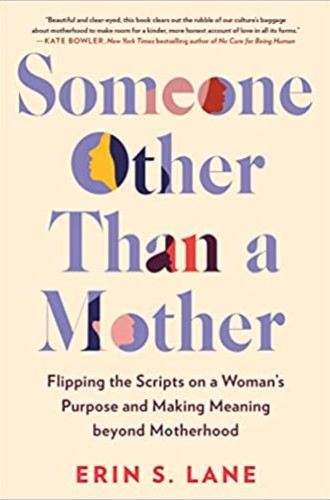

How do we make meaning beyond motherhood? What is at stake for women—both childbearing and child-free—and for society if we do not? These are the questions Erin Lane poses in her second book, Someone Other than a Mother.

Raised in the 1980s on “white bread and Jesus” and taught to be “fervently pro-life” as a Catholic in the American Midwest, Lane was aware that she had more reproductive choices than the generation of women before her and cognizant of the growing anxiety about these choices in conservative Christian circles that touched her life. Her pious childhood led her to a master’s degree at Duke Divinity School, training as a retreat facilitator with Parker Palmer’s Center for Courage and Renewal, and writing about contemporary faith and culture. It also gave her the resources to articulate more deeply the prayer she’d known since childhood, that she wished to be a “soul before a role.”

There was only one problem: maternal exceptionalism. It was deeply rooted in scripture, Western philosophy, and US political rhetoric. It dripped from the tongues of nearly every woman of childbearing age, as well as those who had aged out but fulfilled their procreation duties: Children are a gift. Home is the highest duty. Family is the greatest legacy. You will regret not having kids. You’d make a great mom. It’ll be different with your own. You don’t know love until you become a mother. Each chapter of Lane’s book is devoted to a myth that everyone with a womb has heard.

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt addressed the National Congress of Mothers, lauding the role of women raising children as the bedrock of a moral and productive society:

The woman’s task is not easy . . . but . . . when she has done it, there shall come to her the highest and holiest joy known to mankind; and having done it, she shall have the reward prophesied in Scripture; for her husband and her children, yes, and all people who realize that her work lies at the foundation of all national happiness and greatness, shall rise up and call her blessed.

The women in the National Congress of Mothers were concerned by the conditions of too many children at the turn of the 20th century: orphaned and unprotected, working in mines, or incarcerated with adults. According to Lane, these women were “pioneers of the child welfare movement” who believed caring for the next generation “required skill and support.”

But beneath Roosevelt’s praise of women’s innate care for the welfare of children, Lane sees an ulterior motive and a capitalist deflection of responsibility. She explains:

A country can deflect welfare responsibilities if it casts the home as a public service. A country can grow faster, cheaper if it casts reproduction as a woman’s purpose. . . . To put it crudely, women are meant to feel for their own homes, their own children, precisely so that men—and the government—are free not to.

Roosevelt’s speech, which accuses women with two children or less as having “forgotten the primary laws of their being,” sets off alarms for readers in our post-Roe context, as a host of state laws seek to deny people the ability to choose whether or not they will become mothers.

At the beginning of the book, Lane describes her intentionally child-free life as a “ministry of availability.” When the resources of time and a spare bedroom go unused by busy friends in need of parental respite, she and her husband decide to go into fostering. “Childfree, my life garnered the blank stare. Mothering, I got the gold star.”

Lane is a retreat facilitator trained in helping others to let their lives speak, and her narrative strength is in revealing how the stories we tell ourselves affect who we become and how we love others. In conversation with her friends of various cultural backgrounds, she ponders the twists the motherhood scripts take in more marginalized communities than her own. Many have had to fight for their rights to parent in a country that has enslaved Black maternal labor, denied immigrants access to health care, separated Indigenous children from their families, and denied queer parental rights.

Lane felt the injustice against poor mothers every time someone saw her out with her three foster girls and called her “Mom,” in a way that erased the mother the girls already had and loved. “It was like people were rooting for me, not her. If she received the same government payments to raise her kids that we do now, surely she wouldn’t be called a saint but a drain on the system.”

Lane proposes that motherhood myths hurt all women. Women bear the major responsibility for birth control and the economic consequences when that control fails, both in wedlock and outside of it. One source tells her: “Motherhood is the single biggest risk factor for poverty in old age.” This is in large part due to what sociologists are now identifying as the “motherhood penalty.” The American Association of University Women reports that in 2021, mothers made 70 cents for every dollar paid to fathers, while childless women made 96 percent of what their male colleagues made. Mothers, who make up 41 percent of the breadwinners, are further penalized by the high cost of child care and a lack of paid leave. The accumulation of decreased earnings and unpaid time off to raise children means that women have only 32 percent of the accumulated wealth that men have.

What Lane calls the “spiritualization of the home” has done more than shame childless women and blame mothers for their discontent. It provides a justification framework for corporate policies that insist that motherhood is a profession that competes with the workplace rather than complementing it. This ideology also inspires laws that offer more protection to the unborn than support to the women-headed households tasked with raising them.

More than just meaning making is at stake for women when it comes to the choice to be a mother in the United States. The rate of abortions in the United States decreased in the decades after Roe was passed, but abortion rates are still deeply tied to economics. In 2014, 75 percent of women who had abortions had an annual household income under $30,000.

Lane recognizes the immense privilege of her position when faced with a choice about adopting the three girls whom she and her husband were fostering. “If I was ever going to become a parent in modern-day America, this was the way I wanted it: consensual, communal, subsidized. This is the way I want it for all parents, mind you.” Here her voice is more powerful than that of the pious Catholic schoolgirl who prayed for the qualities of her future husband, secretly hoping he’d accept her desire not to have children of her own.

Someone Other than a Mother opens a broad conversation about how the over-spiritualization of our roles in life can damage our bodies and souls and those of others.