March 2, Ash Wednesday (Matthew 6:1-6, 16-21)

Some years the message of Ash Wednesday feels more tender than others.

In the weeks before my mom died, I spent a lot of time in the medical district of Rochester, Minnesota, where she was being cared for at the Mayo Clinic. It was, in many ways, a holy time. And it was also exhausting, in every way you can envision. There was a sort of fog that descended upon me, rendering me unable to order succinctly in restaurants, remember details like my address of 15 years when checking into hotels, or cross the street with any efficiency. There should be a sticker or something available to people in such situations that would alert the bartenders and servers, the front desk clerks, the world in general to the situation. Psst: I’m walking through the valley of death. Be gentle with me. Give me some extra time.

The restaurants and businesses in the medical district around Mayo are particularly well versed in dealing with people in those situations, and on more than one occasion I was given care that went beyond the call of duty, without having said a word about what was happening. It was like they just knew. To be fair, they probably did; they’d seen the signs of fatigue and grief and stress before.

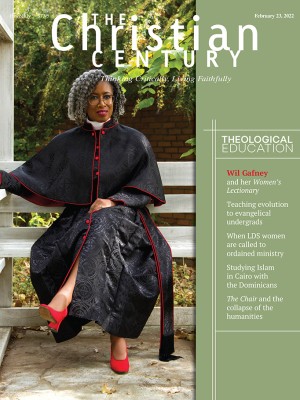

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

On Ash Wednesday, we wear that sign, don’t we? We wear that sign for the world to see, smudged onto our foreheads, that proclaims: we’re dust, and to dust we are returning.

It’s always felt like a strange contrast to hear from our Gospel reading that we shouldn’t be like the hypocrites who disfigure their faces while fasting—on a day when we smudge ashes on our foreheads. But we aren’t practicing our piety before others in order to be seen or to show off. Instead, we’re proclaiming to the world a radical truth: we know that we’re dust. Holy and beloved, but dust all the same.

And that’s where we are all headed together: back to dust.

This pause on Ash Wednesday, when we offer up our foreheads to receive the ashen cross, is full of reminders. During worship we confess and remember that this, too, shall pass: this day, this season of our lives, this struggle, this joy, this heartache. All of this will end, and we will return to the dust from which we began. But how quickly I forget, as I merge back into daily life that has me running errands, visiting people, stopping at the grocery store, that my forehead bears this message to the world—a billboard for mortality.

Last year, our congregation was still worshiping remotely, and we handed out small packets of ashes for those who desired them for at-home use. Friends of ours asked if they could have some too. Later they shared that they had tasked their youngest child, a middle-school-aged boy not known for his gravitas, with marking his parents’ and siblings’ foreheads and uttering the words, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” While initially fearing that the occasion might end with bits of ashes all over the house, they were all taken aback to recognize the tender truthfulness of the moment.

Some years the message of Ash Wednesday feels more tender than others, for a host of reasons: because a loved one has died; because a diagnosis has made death feel more imminent and all the more real; because we’re holding an infant, newly marked with the water of grace and now smudged with ashes; because we’re statistically closer to the end than to the beginning; because we appreciate life differently this year than last; because the death count from COVID continues to rise; because the cross that we wear proclaims to the world, “I know I’m going to die.”

We hold back our hair or lean forward, and we receive the reminder that we are dust, and to dust we shall return. We receive God’s mercy—God’s love and tender grace—traced upon our foreheads, fed to us at the table, a beverage and a small bite to keep us going as we move through our lives until the end. The sign on our lives proclaiming that we know we’re going to die, but that even death isn’t the end of our story.

We gather around water and the word, around the meal and the confession, aware of the story in front of us, the story of Lent: a somber story that startles us from the ways life lulls us. But we experience this story together, in community, seeing the ashes on each other’s foreheads, walking together, kneeling together, being fed together—knowing the tenderness of the day for each other, for we aren’t navigating these days alone.