I stand in front of the altar, looking out at the congregation. The room is packed, and morning light streams in through the funky midcentury stained-glass windows. When I’m nervous, I tend to dance around a little instead of standing still. So I glance at my feet just before I begin preaching—I don’t want to misjudge the edge and fall down the steps.

We are celebrating the feasts of All Saints and All Souls, an occasion when, right on the heels of the humor and mischief of Halloween, we turn our hearts toward all those we love and see no longer. We remember people formally recognized as saints and also those whose wonder and grace will be largely forgotten.

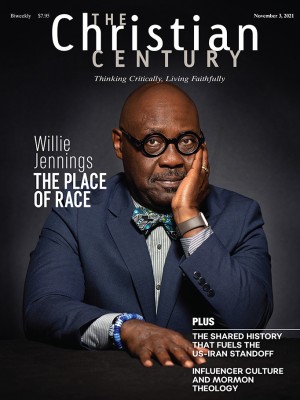

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It has been less than four years since my newborn son died and just over five since I lost my mother to suicide. Days like this one are still raw for me. They are particularly challenging days to preach on, but that is the path I’ve chosen: between these two deaths, I was ordained as an Episcopal priest. While our sacred stories always intertwine with our lives, in this case there is no question. I am living this story every day, especially with our youngest child, Sam, now two and a half years old.

In my sermon, I speak of a recent night when bedtime was a slog. First Sam needed water, then help finding something, then more snuggles. Then he turned to the preacher’s kid’s classic stalling tactic: asking for another prayer. Tired and annoyed, I took a deep breath. “God, pour out your blessing on Sam,” I began.

He promptly interrupted me. “Who poured out my ashes?” he asked.

“What?” I replied, having heard his words clearly yet not comprehending them.

“Who poured out my ashes when I was a baby?” he asked again, more insistently. I took another deep breath, shaking my head in the dark. I explained to him that no one had, because he hadn’t died. “I’m alive?” he asked. Yes, I assured him. So very, very alive. Sam has been asking questions constantly about his brother Fritz, our second child, who died before Sam was born. He was still for a long moment, and then asked me, “Who came?”

Under the wide rafters of the sanctuary, I pause to take in the full pews, all the people here, themselves a living witness to the story. “Who came?” I continue, feeling myself trembling slightly. “He’s been fascinated by this one. Who came for his brother’s funeral? Who showed up? Who poured out his ashes? Who threw the dirt?” This is the story my son wants to hear, again and again. We rehearse the guest list, all these beloveds who came to help us bury Fritz, those who embody for us the communion of saints. They stood close around us in the kicked-up dust, their hands still coated in dirt fresh from the grave.

I am not necessarily supposed to be preaching about all this, to be sharing so candidly what this day churns up in my heart. Some of the more traditional mentors will coach seminarians to “preach from your scars, not your wounds.” The congregation is not your therapist! they insist. I agree with them, wholeheartedly. Healthy boundaries are critical. Yet I also wonder how authentically I can engage our sacred stories without acknowledging how my own grief both informs and sometimes challenges my faith. These stories are never far from me, especially in the pulpit.

When I greet parishioners after the service, some take my hand with pity. Some come forward with palpable awkwardness, offering platitudes or advice that purports to somehow solve the problem of this dead son of ours. But from still others, I register vivid relief, deeper connection, and—most astonishing to me—gratitude. I tell them the truth of my sorrow, and they reply saying, simply, “Thank you.”

How was it that some people could receive this story not as a rueful burden but as a gift? How might I continue to share it, I wondered? For whom, and why? I didn’t know the answers, not fully, but I felt the tug to write. Homilies, yes, but also to write in service of healing, both others’ and my own. I doubled down, kneading my narrative of death and, slowly, of new life. I wrote it all out so that I myself could hold it, and maybe—I wasn’t yet sure—so I could tell my story, too.

Entering in with such immediacy and purpose terrified me, but I kept coming back to the page, trying to find the words to set down what I’d lived somewhere outside my body. I feared I would get stuck in the story, so mired in the sharp memories and still-present grief that I’d miss the life happening all around me when I emerged. I worried, every time I wrote, that I would return to my living kids numb, unable to engage their wonder or be present for their needs and delight. Still, I wrote.

Another year passed, my kids now three and a half and just shy of seven. My mom’s suicide had gutted me, and there had also been a corollary fear: How would I ever tell her story to my kids? How do you explain a death like that? I didn’t want them to inherit the shroud of secrecy that so often accompanies addiction and suicide; I also had no idea what to say. I had comforted myself by insisting that they weren’t ready, they were too young—that I’d figure all this out down the line.

But when I finally closed the teal cover of a three-inch binder over my first attempt at chronicling my grieving and my living, it struck me. It was never that my kids weren’t ready for it, though their now more-developed language was helpful. I had been the one who was not prepared to tell them the truth, to carry this sad story into their young hearts.

In the quiet of the morning, in the same room where I had learned of my mother’s death six years earlier, I pulled my son and daughter close. Cuddled in a nest of all our extra pillows and blankets thrown together on my bed, I told them gently, and with all the courage I could summon, that I had a sad and important story to share with them. “I want you to have the whole truth,” I said, “and I want you to know that you can ask all the questions you have, right now or anytime later.” They were quiet, waiting.

I held my kids a little too tightly as I explained how my mom had been sick for many years, pausing to define key words like “alcohol” and “addiction.” I told them how sometimes when a person’s brain is very sick, it can be difficult to make good decisions, and sometimes people can decide they simply do not want to keep on living. I told them that this had been their grandmother’s choice, and I told them how she jumped. I told them that I wished she had gotten more help, that there is always help. I said how desperately I still missed her. Finally, I stopped, drew a long and shallow breath, and clutched their small bodies for ballast.

In the quiet after I finished speaking, my daughter, Alice, asked just one question: “Who was it who told you, Mommy?” When my mom died, that is, who told me the story?

It matters, she seemed to be reminding me—it matters so very much that we tell these stories. It matters who tells them, and when, and how. The very act of telling them changes us, too, reshaping us as these words are received. Sitting with my kids, relieved and exhausted from the act of sharing this truth, I realized that while I will always carry this pain with me, it no longer terrifies me. Telling my story freed my body and mind of the weight of carrying so much sorrow in myself alone. Having written it all down, I found I could live with this story.

Yes, of course we miss the mark. I have overshared, and I’ve shared too soon. I’ve shied away, omitting too much of what’s real; I’ve been held back by shame or fear. And still, if we’re going to find our way and find each other, we need to answer my son’s question with our own lives. Who came? So many. And we do now. We come to the grave, and we come also for great joy. We come together to tell the story of our hearts and to receive the same from another. We come to hallow that space of truth shared aloud, reverencing it by bearing witness. We then can walk away from that space transformed, now able to really live.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The stories that change us.”