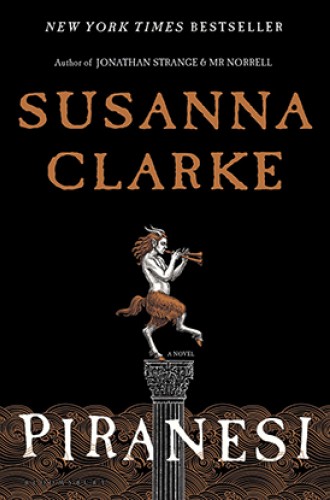

Piranesi is the best kind of fantasy novel

Susanna Clarke weaves magic into her readers’ lives.

Magic doesn’t exist, and yet it has captivated us for centuries, reaching across countries and cultures. There’s a whole genre of fiction devoted to it: fantasy works featuring child wizards, enchanted blades, and dragon queens, aiming to thrill and delight readers with larger-than-life characters, threats, and escapades.

Many fantasy books flow out of the mind as easily as they flow into it. Their plots often feel too convenient to resonate with our lives. Their characters rarely challenge our ways of thinking or feeling. Their worlds feel so distant and disconnected from our own that once we close the books, they no longer echo.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Piranesi is not one of these hollow tales. Instead, it is the best type of fantasy. It doesn’t just allow us to explore a magical world; it weaves magic into its readers’ lives. In these beautifully written pages, Susanna Clarke transforms the way we see our world and ourselves.

This transformation is quite literal, and Clarke begins by rooting us in an alien language, mind-set, and setting. The book opens with a great deal of world building that will feel familiar to any fan of fantasy or science fiction—but that others might find off-putting. The world building is intentional, though. Those who persist, allowing the voice and ideas to wash over them, will find an innocence and joy that set Piranesi apart from most contemporary literature. It’s this early world building, more than anything else, that pulls us out of our daily lives and allows Clarke to lure us into her spell.

What is the world Clarke creates? It is a house. More precisely, it is the House. According to the novel’s main character, and one of the House’s only residents, the House is everything. It is a massive, monolithic, and mysterious world of giant, echoing chambers that stretch for miles in every direction. These chambers are full of ancient statues, all distinct from each other.

Although the House has but three floors, the top floor opens to the moon and stars. Clouds float through it and rain falls into it in the places where the roof has collapsed. The bottom floor opens to oceans where the protagonist, Piranesi, collects the fish and seaweed that sustain him. There’s a certain magic in the conceit of a house with clouds and oceans, but there’s an even greater magic in how Piranesi relates to the House. He loves it, and he feels loved by it. Christians might recognize here something of the idea of God’s presence in the world.

This idea, however, never occurs to Piranesi. As a narrator, he is a fascinating mystery. His voice is delightfully innocent and direct, yet Clarke gives us plenty of reason to doubt him, even from the outset. For starters, he estimates his age somewhere around 35 years old and says he has lived in the House as long as he can recall, except his memory doesn’t go back further than several years.

Piranesi touches on the many uses he has for the fish leather and seaweed that the House provides in its oceans. But he also has journals, in which he writes about his exploration of the House and of the many gifts given to him by the Other, the only other resident of the House. These gifts include such things as plastic bowls, socks, a sleeping bag, a watch battery, boxes of matches, and bottles of multivitamins. These gifts, and the Other, feel out of place amid vaulting halls kissed by clouds and washed by crossing tides, and they offer the first hints that Piranesi’s understanding of his world may be woefully lacking.

Inevitably, this tension opens into a delightful mystery that propels the book forward. This contrast between the magical and the banal connects Piranesi to Clarke’s first novel, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell (2004), which follows the exploits of two English magicians throughout the Napoleonic Wars. It’s a clever and inspiring work of alternate history in which the titular characters are audacious enough to pursue practical magic at a time when the other magicians have resigned themselves simply to the theory of it all. Clarke’s Old England is populated by people who have stopped noticing. Magic flows through the land, sea, weather, and animals. It seeps into our world from the land of fairies, and it simply needs to be called forth once more.

Piranesi is also full of this pervasive magic. There are no wizards with wands, no magic weapons. The novel’s magic is that of seeing the world differently, of speaking to it and of listening to it. It is, when all is said and done, a story about spirituality, about longing to connect with forces and entities we cannot touch or see.

Piranesi is a compact novel, but it makes the world feel larger. When I finished the book and closed it on my lap, I took a breath and looked around me. I saw how the afternoon light slanted through my window, and I heard my children playing upstairs. I let the air out of my lungs, and I could feel myself as a confluence of flesh and spirit.