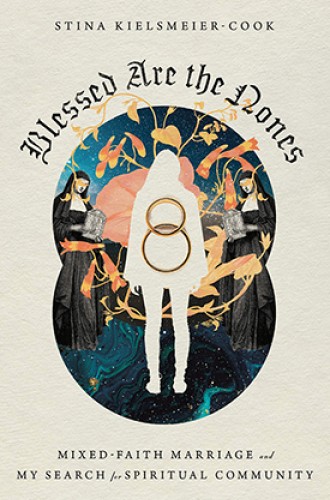

When your partner loses faith

After Stina Kielsmeier-Cook’s husband became a none, she reached out to some neighborhood nuns.

Over the last nine years, various parishioners have left the church where I serve as rector. The most troubling exits aren’t those of people who are uncomfortable with the denomination, who dislike me personally, or who disagree with a policy or a doctrine. The departures that keep me awake at night are those of people who no longer believe. Such members unfailingly reassure me before they leave that they care about me and other members; they simply can’t participate without belief. They’ve joined those who list their religion as “none.”

As painful as these departures are, I imagine it would be far more difficult to experience the deconversion of a family member—especially an intimate partner. This is the subject of Stina Kielsmeier-Cook’s new book, an in-depth exploration of how her husband’s loss of faith has affected her and shaped her own spirituality.

The couple met at Wheaton College, where they read the Bible together and discovered that “our shared belief in God was the deepest part of our connection.” But several years into their marriage, between the births of their two children, Josh stopped believing—and the author suddenly found herself in a mixed-faith marriage. How could she faithfully continue in this union? She writes, “After so much time in Protestant churches that center on the traditional Christian family, I don’t want a self-help guide on how to pray my husband back to faith. Instead, I need hope that my interfaith marriage isn’t an affliction I need to bear but a vehicle through which God can move.”

Kielsmeier-Cook, who has experimented with various expressions of Christianity in her life, eventually found what she was seeking through some Catholic sisters. The route was somewhat circuitous. Her initial attraction was to a group of Benedictines who live about an hour from her home, but the distance proved problematic for a parent of young children. One Halloween, while taking the children trick-or-treating, she happened to meet a group of Salesian nuns who live in her neighborhood. These nuns, who belong to the Visitation Sisters of Holy Mary, invited her to mass. She later learned that they host a group of Visitation Companions who meet for a yearlong spiritual formation process, praying together and learning about the Salesian order.

The term “spiritual singleness” came to Kielsmeier-Cook while she was hiking alone one day. As she went off-trail, she reflected on how drastically her spiritual journey had veered from the expected path for evangelical Christians: find a Christian spouse, attend church together, attend Bible study together, find a small group to join. She thought about how Josh’s deconversion had left her feeling single in her faith. She wondered whether nuns and monks, with their vows of celibacy, might be able to help her find a connection to God apart from her husband.

Blessed Are the Nones follows Kielsmeier-Cook’s journey over the following year. She began paying attention to the feast days for women such as Dorothy Day, Elizabeth Lesler, and Saint Monica. She immersed herself in holy days like Palm Sunday and the Feast of the Visitation. (One particularly poignant chapter describes how she and her children were accidentally left behind during a Palm Sunday procession.) She studied Salesian spirituality and continued to learn about Benedictine spirituality as well. She began to reimagine the evangelical praise music of her youth from a Benedictine perspective. (“Open the eyes of my heart, Lord” became “Help me to rest and say no, Lord.”)

Kielsmeier-Cook is a millennial and writes from that generational standpoint, but her book speaks to me (a Gen Xer) and is likely to appeal to members of other age groups as well. She writes about the impulse to keep searching, “turning to faith practices that have stood the test of time, yearning for stability in a world that feels chaotic,” but acknowledges that such spiritual wondering and wandering concerns her. What if she keeps chasing after something rather than settling deep into one tradition?

One of the book’s strongest chapters, “Relinquishment,” is set during Lent, a time when many Christians relinquish something for a season. Kielsmeier-Cook describes a practice she learned about during her spiritual formation program with the Visitation sisters: “suppressing a monastery,” or helping it to close well. She recalls that her friend Amy, preparing for ordination in the Episcopal Church, had once asked her, “How can I love a dying thing?” Kielsmeier-Cook turns this question onto herself: “How can I hold onto faith as I watch so many of my peers walk away from the church?”

As she watches the sisters in her neighborhood help another convent close down, Kielsmeier-Cook glimpses some hope for her own situation:

The sisters who remain model a profound trust in the Holy Spirit to take what has been lost and transform it into something new. To let go of control, to relinquish their communities to God, even as they keep casting sparks around in trust that something will catch fire. The alternative is fear: holding things so closely they distort in my grasp. Instead, the Spirit calls me to let go, let go, let go. Relinquish Josh to God again and again.

Drawing on wisdom from Richard Rohr, she concludes: “To love a dying thing is to let it go, to let your love extend beyond religious conditions. To love a dying thing is to trust that, in the dying, Easter is still coming.”

By the book’s end, Kielsmeier-Cook has not prayed her husband back to Jesus. She’s also learned that her phrase “spiritual singleness” does not resonate with her beloved nuns. But she has started an interfaith small group for couples with similar imbalances of faith, as well as a group of millennials who meet with monastics—a “nuns and nones” group—for spiritual conversation.

Ideally, spiritual memoirs reveal large truths through personal experience. This one does just that. The way Kielsmeier-Cook turns her personal journey outward to include other interfaith couples, nones, and Catholic sisters will inspire readers at any point on the religious-to-none spectrum.