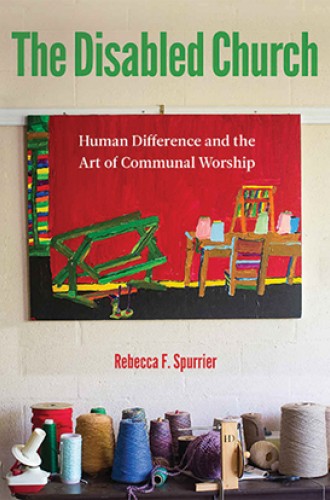

When liturgy embraces difference

Rebecca Spurrier’s study of a “disabled church” and its lessons for all Christians

At a time when many Christian communities seek to make diversity a crucial aspect of ecclesial unity, belonging, and participation, Rebecca F. Spurrier makes a poignant contribution. Rooted in her multiyear ethnographic research at a congregation she calls “Sacred Family Episcopal Church,” Spurrier’s book is an extended reflection on Christian liturgy through and across difference. Her account of the liturgical life at this church (many of whose congregants live with some combination of mental illness, poverty, and disability) provides a much-needed addition to the field of disability theology. Not only does she demonstrate a sophisticated interdisciplinary engagement with disability studies and liturgical theology, she offers pastorally relevant proposals for diverse Christian communities.

At the heart of the book lies a pressing question: “What do you need in order to have a church that assumes difference at its heart?” Spurrier believes that human experiences with disability and mental illness usher us into the artistry and beauty of Christian liturgy as a space of encounter with people “whom we would not otherwise choose.” The relationships forged in this space, marked by consent and nonviolence in response to God’s love, make “possible belonging to a community through and across difference.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As these relationships emerge, they resist both the erasure of difference and unhelpful loyalty to narrow sets of normative practices. Spurrier defines Christian liturgical practice broadly, informed by those she meets at Sacred Family. She includes eating, joking, and conversing together as well as celebrating the Eucharist, baptism, and confirmation. Her expansive vision welcomes gesture, touch, and silence in the liturgy. It rejects the idea that literacy, cognitive assent to belief, and verbal proclamation are the only acceptable forms of liturgical participation.

In considering the practices of ecclesial life at Sacred Family, Spurrier embraces what she calls a “theological criterion of beauty.” She appeals to Edward Farley’s idea of a theological aesthetic, in which

beauty, as a theological term, marks the lived experience of one’s outward turn to another, a turn both passionate for another and restrained by the needs of the other. As we turn to the ones who call to us, through their need for us to turn, we become beautiful, and the turning arouses our interest and desire in the beauty of another.

At the same time, she draws upon Serene Jones’s notion of theological aesthetics, which attends to the particular qualities people regard as beautiful (or not) and notes the “affective responses and embodied interactions” that result. Spurrier uses both of these frameworks as she assesses “the communal life of Sacred Family: its hopes and fragilities, its strange humor and its suffering, its cohesion and incoherence, its consent to difference and its powerful hierarchies of ability, wealth, and race.”

Part of the deep beauty of the book is rooted in Spurrier’s expression of her extended practice of “loitering with intent” at Sacred Family. Drawing upon the work of theologian and “crip philosopher” Sharon Betcher, Spurrier maps interdependence as she loiters in various spaces—the smoking circle at the picnic tables outside the church’s east door, the sanctuary during noonday prayer, the bingo table near the coffee station at the community breakfast—and notes the presence and absence of disability, racial difference, and diverse class identities. Spurrier’s rich expression of the interactions she observes at these multiple gathering points made me laugh at times and cry at others, heightening my sense of theological curiosity and delight.

Throughout the book, Spurrier illustrates how disability can help us recenter the beauty of fragile human connections in worship life as we access both our neighbors and the divine. For example, when she hears Wallace and Joshua commenting with pleasure after receiving holy communion one day (“That was tasty!” “Yeah, that was real tasty!”) she notices that “their enthusiastic commentary on the Holy Eucharist occasions a different sense of worship through and with them that day. They create a new connection for me to the dry wafer I just consumed, to the words ‘The body of Christ, the Bread of Heaven.’”

Spurrier focuses on particular identity markers common to Sacred Family’s parishioners, staff, and clergy: experiences of disability, poverty, and mental illness. At the same time, her book speaks to larger questions about embracing diversity that arise in churches across the ecumenical spectrum. Her arguments for liturgical participation and belonging as “art forms” that center categories of beauty, consent, pleasure, and desire are applicable beyond the realm of scholars and pastors with a specific interest in disability.

The Disabled Church demonstrates the plain truth that disability relates, disrupts, and weaves into the ordinary work of Christian liturgy across all kinds of practices and contexts. Spurrier artfully integrates disability into familiar conversations for Christian faith communities, highlighting disability’s intimate connections with concerns for justice, consent, and desire. In this way, she invites pastors, practitioners, and scholars unfamiliar with disability to have a seat at the table and settle in for the long run. Across a diversity of practices and traditions, her book offers support for Christian disciples as they reimagine, reenliven, and reembrace liturgy through human difference.

Spurrier is careful to resist highlighting Sacred Family as a model parish that can be easily replicated in other places where Christians gather. This book is not a manual. Instead, it provides a poignant example of “disability gain,” a framing of disabled experience that points to what is gained (rather than what is wasted, lost, or jeopardized) when disability is embraced. In this way, Spurrier’s account of life at Sacred Family provides “a window into the kinds of aesthetic frames and questions that a disabled church” provides for all Christians.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Beauty in belonging.”