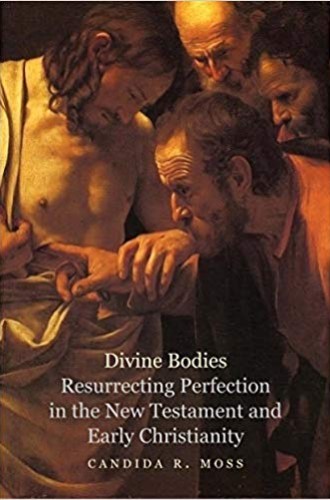

Candida Moss asks what bodily resurrection means

How early Christians thought about bodies and how we do

Tell me about your idea of bodily resurrection and I’ll tell you about your anxieties and joys. In her “narrative autopsy” of early Christian ideas about what happens to our bodies after we die, Candida Moss shows how every aspect of the resurrection of the dead is (and has always been) fraught and contested. That’s true both for regular people’s corpses and for Christ’s, which she calls the “most burdened body of the New Testament.”

As she eavesdrops on ancient conversations—in which the “self” that survives death is rarely what we modern people think of as ourselves—Moss teases out the logic of early Christian texts in their context. In these pages, Aristotle’s goal-driven universe encounters Pauline spiritualized bodies; medical treatises converse with Homer’s and Virgil’s reanimations.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This lively investigation is not mere abstraction for Moss, a scholar of early Christianity and New Testament who teaches theology at the University of Birmingham. Her inquiry starts from her own body: while convalescing from a kidney transplant, she wonders whether having someone else’s organ makes her a new self. As the book proceeds, she teaches us how to read our sources and our own bodies while seeking understanding through the original context.

Moss shows, for example, that it matters whether the apostle Thomas, in his moment of doubt, reached for a wound or a scar. Scarring happens after a few days, she explains, so a scar would prove that Thomas was touching the same body that had appeared to the disciples a week earlier. I hadn’t thought of that before.

Nor had I thought about the fact that heroes in the ancient world had scars. So even after being given a new view of kingship and heroism, the communities around Jesus may well have been working with an older understanding of the heroic journey as they described Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances. Was it a wound or a scar? Is wholeness perfection or evidence of cowardice? Is disfigurement punishment or preventative? These distinctions matter.

Without belaboring her method, Moss is training her readers to approach texts “as an ancient listener,” distinguishing what we care about from ancient concerns.

Moss’s way of reading has the potential to reanimate texts that have become static. Even if we worry in a different way than ancient people did about what our heavenly bodies might be like, we nonetheless hold “the same worries about the self, about the lives we value, and about the lives we never want to have.”

Moss discusses scholarly debates, using terms like “banal aesthetics,” “anti-docetic polemic,” and “apocalyptic hangover,” often with little explanation. But the careful way she weaves together these theories with her sources makes it possible to approach the book from varying levels of expertise. You don’t need to be immersed in the latest historiography debates to hold on to Moss’s thoughtful, nuanced readings of beloved texts. Slowly and artfully, she inscribes her method upon readers—both the experts and those who have never had a course in theory.

Such multiple layers of accessibility can be seen in Moss’s exploration of physical resurrection. She expertly reads the Gospels against one another by “dragging our normally philosophical Fourth Evangelist into the muddy specifics of material resurrection.” The meticulous conversations Moss creates here between various ideas and sources will be useful on one level to those who care about distinguishing between the Gospels and asking if Paul contradicts gospel priorities. They’ll be useful on another level to those who find themselves advising parishioners or students who wonder whether bodies survive past death, spirits are separate from bodies, or a recognizable self will fly to a physical location called heaven. And readers who have never been immersed in such conversations will still grasp Moss’s broader themes of justice, the body as identity, and the relationship between pain and pleasure.

Gently and humorously, Moss welcomes us as coconspirators in her hunt for meaning in bodies. We learn how knowing Homer illuminates our understanding of Mark. We marvel at how we’ve failed to consider how amputations, rot, hair, and flesh inform our theological perspectives. We learn that beauty, like gender, is a “negotiated performance.” We begin to unpack the socioeconomic implications of the way we imagine resurrection. We question how “ableistic assumptions” can interrupt the stability of the category of human body over time. We grasp what it means to say that “the dead create and re-create social hierarchy.” Along the way we get juicy anecdotes about Oedipus’s eyes, Jesus’ foreskin, ghosts, fire-retardant white linen, and miraculous virginity.

Our expectations about what happens to our bodies after we die come sometimes from our sacred texts and sometimes from what we’ve imposed onto those texts. Moss helps us sort through the two. She reminds us of our discontinuity from ancient thinkers regarding beauty, heaven, and human nature—and then she helps us recognize what connects us with them across the centuries.

I imagine readers will leave this book living in their bodies differently. Whether in the scholar’s study or the pietist’s pew, we are all bodies. How we carry them matters.