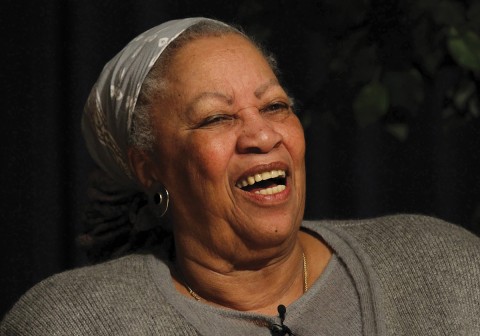

The kinds of stories Toni Morrison told

No one has done more to transform the language for thinking about America’s racial past.

In recent years, visitors to Thomas Jefferson’s plantation in Virginia have received an unvarnished portrait of the Founding Father. Guides at Monticello make it clear that the plantation ran on the backs of enslaved people and that Jefferson, coiner of the phrase “all men are created equal,” bought and sold human beings. The brilliant writer of the Declaration of Independence was the overseer of a forced labor camp.

These facts and ironies are too much to absorb for some white visitors, who complain that guides are bashing Jefferson and politicizing the tour by spending so much time on the African American experience. The Washington Post reported recently that an increasing number of visitors’ negative reviews complain of “political correctness.” Many people don’t want to hear about the shameful past or about what it was like to live in bondage.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

How do we talk about the past and tell the complicated truth about our identity as Americans? It is, inevitably, a political question, for it asks us to decide whose stories matter and who gets to tell them. The answer we give is powerfully shaped by the language we choose. Do we refer to “Mr. Jefferson’s people” or “enslaved people”? Do we say that Jefferson fathered children with Sally Hemings or that he forced himself upon a woman he owned?

No one has transformed the language for thinking about America’s racial past more than Toni Morrison, the Nobel Prize–winning novelist who died August 5. This issue of the Century contains a reflection on one neglected aspect of Morrison’s work—her effort to express the religious depths of African American life.

Morrison reinvigorated language about racial experience not primarily through historical argument but through novels that immerse the reader in diverse and complex black voices. Her novels are notably indifferent to the reactions of any imagined white audience, politically correct or not. In a documentary film titled Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, she commented, “I have had reviews in the past that have accused me of not writing about white people . . . as though our lives have no meaning and no depth without the white gaze.” She went on: “I have spent my entire writing life trying to make sure that the white gaze was not the dominant one in any of my books.”

In her Nobel lecture in 1993, Morrison warned of succumbing to a language that is “unreceptive to interrogation, [which] cannot form or tolerate new ideas, shape other thoughts, tell another story, fill baffling silences . . . a language calculated to render mute the suffering of millions.” She held out hope that writers could find a language that does justice to the distinctiveness of individual lives. That kind of “work-work,” she said, is “sublime.” She imagines her muse saying, “Tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light.” She did that, brilliantly. Her readers get the opportunity to listen.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Who gets to tell America’s stories?"