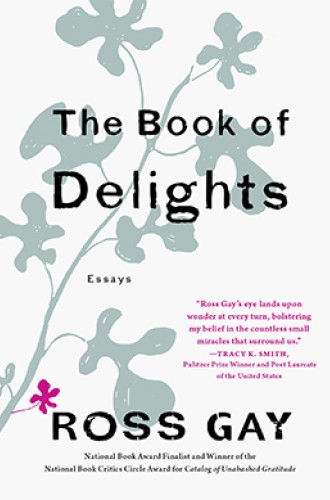

In times of national or personal pain, the temptation is to go speechless, to become inert, to rage and destroy, or simply to weep. Ross Gay’s collection of short essays offers us another option: joy.

Gay, the author of three poetry collections and winner of the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award, began his “book of delights” project as a collection of daily essays handwritten over the course of a year, each about “something delightful.” His warm and casual style invites us into the “common flourishes” of his everyday life. We’re with him at the café, on an airplane, in the garden, at a friend’s funeral, and all the while we feel that he sincerely wants us there. Gay is the ultimate host: generous, engaged, and seriously funny.

Delight emphatically sprawls across the pages in brazen celebration of the quotidian. The effect can be dizzying, the prose at times a little cute. Yet the startling violence and loss that Gay weaves throughout the collection requires a certain boundless freedom of language. In one of the collection’s most pointed moments, Gay, with brilliant clarity and concision, unravels the relationship between blackness and suffering and reminds us, “you have been reading a book of delights written by a black person. A book of black delight. Daily as air.” In these sharp and clear moments of disclosure, Gay’s work becomes revelatory.