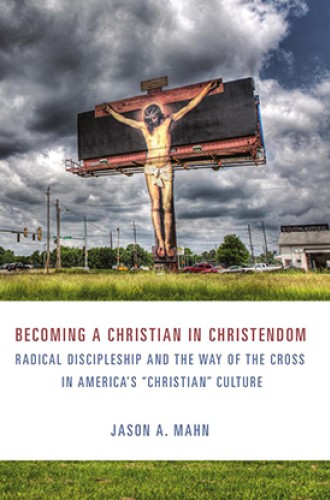

Still resisting Constantine

According to Reformation scholar Jason Mahn, the birth of Christendom was a sort of Fall.

Reformation scholar Jason Mahn implies that authentic Christians—those who are stubbornly and earnestly true to the Gospels—are few and far between. According to Mahn’s diagnosis, nominal Christians, especially American Christians, have accepted too readily the priorities of the neoliberal state. We have embraced the consolations of the consumer society, and we have accepted military victories and sacrifices as essentially holy. In the process, we have forgotten the nonconformist who hung and suffered on the cross to prove that, in a face-off with corrupt or mistaken state power, he would rather die than kill. Jesus, properly understood through a theology of the cross, embraced his weakness in order to live with us and to teach us how to suffer for what is deeply and truly right.

Mahn’s heroes are Søren Kierkegaard, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and a group of contemporary religious historians and theologians he calls anti-Constantinians. These are contemporary thinkers who lean toward pacifism, such as John Howard Yoder and Stanley Hauerwas, African American and feminist scholars with their own critique of the American church, and liberation theologians with their vision of a radically new and just society. What these thinkers have in common, apart from their call to peacemaking, is their disgust for Christendom—the normalized, apparently inoffensive, consoling Christian church community that too often half-consciously aids and abets a cruel and violent larger society.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As Mahn recounts it, the story of Christendom began in the early 300s CE when the Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and legalized his new faith in all Roman lands. Soon Christianity ceased to be a beleaguered, denigrated faith of a powerless few who sought to remember and listen to the crucified Christ. Through its new legal status—and certainly through its own arguments and charms and the work of God—its adherents spread across Western Europe and transformed its ways. Christianity became the faith of the West.

It seems a triumphant story. Yet, for Mahn, it is another version of the Fall. Christianity had become a club with (eventually) millions of new members, but now the faith had to make peace with state and church power. Over the centuries, this process has led to heresy, error, and corruption. The church has gained visibility, wealth, and social sanction but has been largely co-opted by nationalist aims—sometimes including war making, unjust discrimination, and the sustaining of unwarranted privilege. It would be better, Mahn argues, to return to the beliefs and ways of the early denigrated Christians who suffered as a despised but more gospel-centered minority sect.

Martin Luther was among the first Western Christians to object to what the church had become: accommodating toward the powerful rather than loving and revelatory for all. Kierkegaard extended Luther’s logic in 1840s Copenhagen, where churchgoers and clergy were unable to distinguish the habits of bourgeois Denmark—habits like seeking pleasure and demonstrating piety—from the faith Jesus taught and the grace he offered. Kierkegaard cried out against this Christendom, taunting its Danish members. Mahn is not the taunting type, but he follows Kierkegaard in making a vigorous and unflinching criticism of a contemporary Christendom that has forgotten Jesus’ teachings about loving the neighbor, healing the sick, feeding the poor, and making peace.

Almost exactly 100 years after Kierkegaard’s attacks on the Danish Lutheran church, Bonhoeffer watched as his own form of Christendom—the Christian church in Germany—lurched much further from gospel teachings, giving in to and endorsing Adolf Hitler’s murderous thievery and triumphant war making. Most of us applaud Bonhoeffer’s resistance to National Socialism, yet fewer know that his writings from Tegel Prison involve a call to profound discipleship and to so-called “religionless Christianity.” Mahn admits that it is difficult to summarize Bonhoeffer’s late writings. But he suggests that a religionless Christianity today would involve less congregating of the like-minded in cozy sanctuaries and more active participation by Christians in the “worldly” processes of conscientious resistance to injustices. Perhaps we church members, Mahn suggests, who strive to avoid becoming worldly are in fact “not nearly worldly enough.”

As for Yoder, Hauerwas, and other contemporary non-Constantinians, Mahn praises them mainly for their courage in calling for “the politics of Jesus” and for a new version of “early Christian counterculture.” He recognizes that Yoder wasted much of his personal moral authority by perpetrating violence on women but insists that Yoder’s Mennonite theology is still a proper roadmap for a peaceable, intentional, dissenting church. Mahn admires Hauerwas for, among other things, his insight that “fighting terrorists [and] fighting diseases have become our culture’s dominant religion.” Meanwhile, Hauerwas also suggests, we have forgotten how to endure pain, abide in silence, and trust God.

As Mahn charts history and weighs arguments, he also writes about his own attempts to live by faith. For example, he tells about a time when he called the police on a troubled neighbor who was acting out. The story illustrates how an earnest believer comes to repent what he belatedly recognizes as a serious mistake, even a sin.

Mahn sees churches as reflective, intentional, nonconforming, and peaceable communities of believers. In his vision, Christians are called to suffer for resisting the beliefs of some of our neighbors and their favorite politicians. Resisting Constantine has never been easy. Mahn reminds us that we aren’t alone in the effort.