Reading Elie Wiesel after fleeing Rwanda

You cannot bear witness with a single word like genocide. Yet Night describes exactly what happened to me.

My eighth-grade English teacher put the word genocide on a vocabulary list. I hated it immediately.

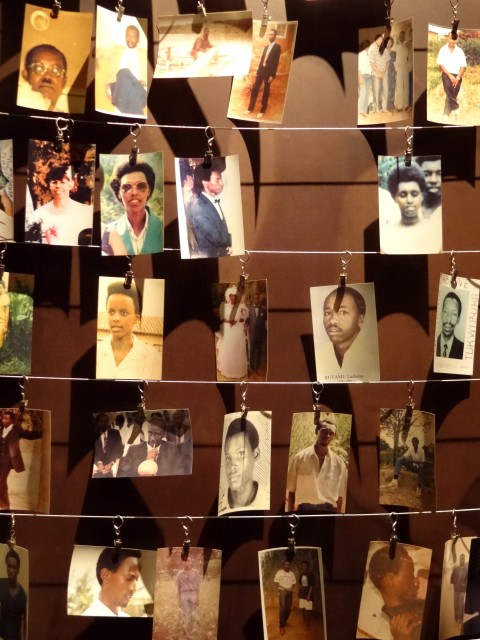

The word is tidy and efficient. It holds no true emotion. It is impersonal when it needs to be intimate; cool and sterile when it needs to be gruesome. The word is hollow, true but disingenuous, a performance, the worst kind of lie. It cannot do justice—it is not meant to do justice—to the thing it describes.

The word genocide cannot tell you, cannot make you feel, the way I felt as a child in Rwanda. The way I felt in Burundi. The way I wished to be invisible because I knew someone wanted me dead at a point in my life when I did not yet understand what death was.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The word genocide cannot articulate the one-person experience—the real experience of each of the millions it purports to describe. The experience of the child playing dead in a pool of his father’s blood. The experience of a mother forever wailing on her knees.

The word genocide is clinical, overly general, bloodless, and dehumanizing. “Oh, it’s like the Holocaust?” people would say to me—say to me still. No, I want to scream, it’s not like the Holocaust. Or the killing fields in Cambodia. Or ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. There’s no catchall term that proves you understand.

There’s no label to peel and stick that absolves you, shows you’ve done your duty, you’ve completed the moral project of remembering. This—Rwanda, my life—is a different, specific, personal tragedy, just as each of those horrors was. Inside all those tidily labeled boxes are 6 million, or 1.7 million, or 100,000, or 100 billion lives destroyed.

You cannot line up the atrocities like a matching set. You cannot bear witness with a single word.

I started reading Elie Wiesel’s Night that year. The book alarmed and comforted me. I wanted to consume it whole. Wiesel was white, European, male, and Jewish. Wiesel was me.

He expressed thoughts I was ashamed to think, truths I was afraid to acknowledge. He described walking in the snow—the cold, the mouthfuls of bread and the spoonfuls of snow, an injured frozen foot that felt like it was no longer his, “a wheel fallen off a car. Never mind.” I had walked in the heat, but it was the same walk—desperate, disembodied, surreal. I couldn’t stop staring at the page. I needed to study every detail, and every detail humiliated me.

I read Night in bed. It transfixed me. Wiesel packed in so much, so efficiently. He loses his name. He loses all sense of himself. The depravity of his tormentors makes him depraved. “Bread, soup—these were my whole life. I was a body. Perhaps less than that even: a starved stomach.”

I was fascinated, perhaps most of all, by his willingness to question the existence of God. No one in my life did that. My mother and sister praised God daily. They never doubted his wisdom. Yet how could God exist?

Wiesel had the only possible answer: God was cruel. “Where is He?” Wiesel writes. “Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows. . . . Praised be Thy Holy Name, Thou Who hast chosen us to be butchered here at Thine altar.”

I could not absorb the book and I could not put it down. Wiesel was—I was—nothing, reduced to nothing, and yet still contained a galaxy of horrors. “I was dragging with me this skeletal body which weighed so much.” “The days were like nights, and the nights left dregs of their darkness in our souls.”

I finished Night in two days. The following afternoon, during a free period, I sat on the classroom couch of my English teacher, Mrs. Ledbetter, and waited. “This is exactly what happened to us,” I said when she entered the room. “The walking. Everything. Strip, strip, strip, then you’re nobody.”

I’d learned a one-word label for the war, or conflict, or whatever it was: intambara. That was the hook on which I tried, for years, to hang all this in my mind. Just that one slippery hook. It was not enough. There is never just one word.

Wiesel acknowledged what no one else I knew did: Yes, this happened. Yes, people destroy each other. Yes, it is intolerable and turns you into a corpse. But still you must remember, and you must carry on.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Words for bearing witness.” It was adapted from The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After, by Clemantine Wamariya and Elizabeth Weil. © 2018 by Clemantine Wamariya. Published by Crown, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.