Safe spaces in dangerous places

Laura Kipnis, sexual assault, and the question of female agency

In a move of breathtaking hypocrisy, conservative critics of higher education, who have in the past monitored and denounced so-called radical professors for exposing their students to subversive ideas such as feminism, gay rights, and racial equality, have suddenly recast themselves as stalwart defenders of free speech on campus. Campus conservatives and the Koch brothers mock universities for disinviting provocateurs like Milo Yiannopolous, but would never dream of insisting that, say, Liberty University invite Cecile Richards, the head of Planned Parenthood, to speak.

To be sure, conservatives have been provoked by organized acts of campus censorship such as occurred at Middlebury College last spring, when student protesters disrupted a lecture by conservative political scientist Charles Murray and assaulted him and a faculty member as they escaped the angry crowd. Faculty declarations like the one at Wellesley College that argued that the mere invitation of controversial speakers can cause students harm by creating a need to “invest time and energy in rebutting the speakers’ arguments” have elicited yet more conservative cris de coeur. The speaker whose campus visit inspired the Wellesley backlash was feminist cultural critic Laura Kipnis.

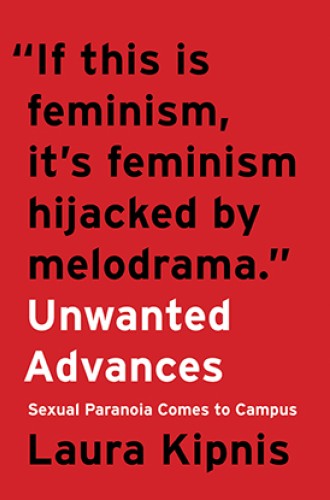

In her spirited new book, Kipnis (whose other books include Against Love: A Polemic, Bound and Gagged: Pornography and the Politics of Fantasy in America, and How to Become a Scandal: Adventures in Bad Behavior) highlights the absurdity of her own position: “When someone like me gets lauded on the right” and condemned by the left, “politics as we know it is officially incomprehensible.”