What words mean to us

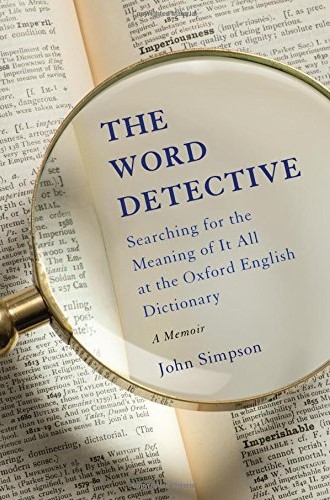

John Simpson's new memoir is about words. More significantly, it’s about our relationship to them.

I remember vividly the first time I became aware of the Oxford English Dictionary. It was the summer after my first year of college, and my friend Jane and I were engaged in a long-distance game of Scrabble. (This was before the days of apps and online interactive games. We set up our boards the old-fashioned way, each at one end of the country, and periodically told one another by phone which new letters we had chosen, which word we had created, and where on the board we were placing it. It was painstakingly and exhilaratingly slow.) At stake was a seven-letter word on a triple word score, and it all hinged on whether the gerund wauling could legitimately be made into waulings. (This was also before the days of a searchable online Scrabble dictionary.) After an intractable disagreement we contacted our favorite English professor for advice, and she wisely responded by telling us to look it up in the OED. I’ve been fascinated with the dictionary ever since.

John Simpson’s lively memoir about the editing, updating, and online debut of the OED gives a glimpse into what the author portrays as a living, breathing book. Simpson, who worked at the estimable dictionary for most of his adult life, intersperses the story of his own life and vocation with the cultural, linguistic, and etymological stories of words. Along the way, there’s drama, sadness, and a good deal of dry humor. “The English are temperamentally obsessed with the presence or absence of apostrophes. It remains for many people a divide between civilization and chaos.” He comments on his office culture with the wry explanation that “the inability to see beyond the past is known to lovers of punctuation as the ‘Oxford coma.’”

Simpson covers the history of many words that are fraught with meaning in today’s world—including gay, disability, and sorry—as well as more mundane terms like spa, juggernaut, and balderdash. He explains how the editors of the original OED deliberately skipped from fucivorous to fuco’d in order to avoid being arrested for gross indecency. He traces patterns in the migration of “loanwords” from Hindi and Japanese into English.