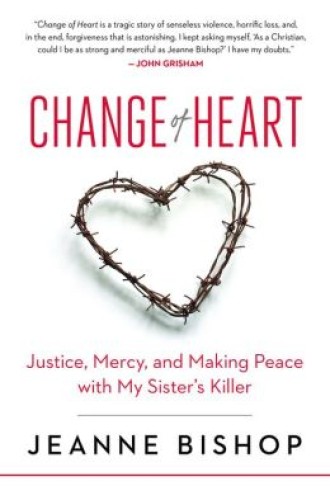

Change of Heart, by Jeanne Bishop

Nancy Langert dipped her finger in her own blood and drew a heart on her basement floor next to the dead body of her husband. Then she traced the letter “u”: love you. She died soon after from loss of blood. She and her husband had been fatally shot by a local teenager in their townhouse in an affluent Chicago suburb. It was April 1990.

Author Jeanne Bishop was Langert’s older sister. When Bishop learned at a police station that her pregnant sister had been murdered, she found herself saying aloud, “I don’t want to hate anybody.” Weeks later, still reeling with emotion, she prayed, “Take this from me, God. Do something with it. Bring good out of this evil.”

Change of Heart may therefore seem like a misleading title. From the moment Bishop learned of the murder, her heart was set on her intent to choose love. But God transformed that intent in a way beyond what she ever imagined. Later, as she describes it, “I felt my heart, hard and rigid, cracking open.”