Making Jesus look good

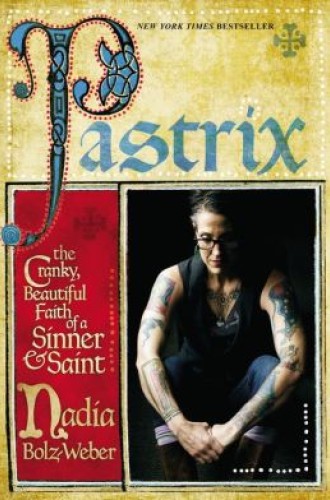

Nadia Bolz-Weber is infinitely cooler than I am. She is probably cooler than you, too, unless you happen to be Bono. As readers are reminded a few too many times in Pastrix Bolz-Weber, a Lutheran, is the tattoo-covered founding pastor of House for All Sinners and Saints (HFASS) in Denver, an emerging congregation populated largely by people who are also much cooler than your typical Century reader.

When faced with such unrelenting coolness, I have a tendency to get a bit defensive. My bruised ego tries to convince me that this must be yet another case of all style and no substance. Surely Pastrix debuted at number 17 on the New York Times best-seller list not because Bolz-Weber is actually saying anything new, but as a result of the extraordinary hype surrounding her “precious little indie boutique of a church.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Yet the attention is well deserved. For all her swagger, Bolz-Weber is a surprisingly vulnerable narrator who pairs personal confessions with beautifully articulated statements of faith. And though she really isn’t saying anything new, she’s telling old truths in the best possible way. She communicates the gospel with more f-bombs than your average person of the cloth, but the crux of her message is the cross of Christ.

Bolz-Weber discovered that she was supposed to be a pastor while she was giving the eulogy for a friend who had committed suicide. In her circle of “comics, recovering alcoholics, and comics who were recovering alcoholics,” she was the sole religious person, having found God—or rather, having been found by God—during her early days as a stand-up comedian in recovery. She writes:

It was here in the midst of my own community of underside dwellers that I couldn’t help but begin to see the Gospel, the life-changing reality that God is not far off, but here among the brokenness of our lives. And having seen it, I couldn’t help but point it out. For reasons I’ll never quite understand, I realized that I had been called to proclaim the gospel from the place where I am, and proclaim where I am from the gospel.

Unlike many clergy who are called and subsequently sent, Bolz-Weber was called in place. She founded HFASS for “underside dwellers” because she was herself one, and not merely in the past tense.

Bolz-Weber refuses to shape her experiences into a classic evangelical salvation story. She is clear that despite significant changes in her life (sobriety, for instance), she is still a broken, imperfect person who is beholden to the grace of God. Her focus on grace is unwavering; if not for the oft-mentioned tattoos, she’d fit right in with the Lutheran pastors on Garrison Keillor’s pontoon boat.

Unsurprisingly, given my mild obsession with Bolz-Weber’s coolness, I was fascinated by the chapter in which HFASS is suddenly inundated by people who are “the wrong kind of different.” A feature story about the church in the local paper had piqued the interest of suburbanites and “baby boomers who wore Dockers and ate at Applebee’s.” These people, Bolz-Weber recalls with blatant derision, “had driven in from the suburbs to consume our worship service because it was ‘neat’ and so much cooler and authentic than anything they could create themselves.” She notes that it wasn’t merely the Dockers that agitated her; she was concerned that the mainstream infiltration would threaten the funky ethos of HFASS, thereby making it less comfortable to the sort of people to whom traditional churches likely would not extend hospitality.

But during a meeting whose hidden agenda was to make all the newcomers realize that HFASS was not really for them, one of the members who was the right kind of different spoke:

As the young transgender kid who was welcomed into this community, I just want to go on the record to say that I’m really glad there are people at church now who look like my mom and dad. Because I have a relationship with them that I just can’t with my own mom and dad.

Bolz-Weber celebrates such juxtapositions:

Out of one corner of your eye there’s a homeless guy serving communion to a corporate lawyer and out of the other corner is a teenage girl with pink hair holding the baby of a suburban soccer mom. And there I was a year ago fearing that the weirdness of our church was going to be diluted.

As is often the case with memoirs, Bolz-Weber’s personal faults beget corresponding literary faults. Her humor is occasionally a hair too sharp, her self-deprecation uncomfortably convincing. Though she is undoubtedly authentic, she can appear overly intent on asserting her originality and credibility. Yet as is often the case with effective Christian memoirs, the reader’s regard for the narrator becomes less important than the reader’s regard for Christ, and Bolz-Weber’s utmost talent is making Jesus look really good.

Pastrix will be received most enthusiastically by people who have been rejected or mistreated by the church; they will find that the gospel is once again excellent news when it is preached by this “female ecclesiastical superhero.” Bolz-Weber’s intended audience may well be those who fit her definition of the “right kind of different,” but it is also for soccer moms and for men in frumpy pants. It is for all who need to hear the radical message that they belong to God, all who need to be reminded how radical it is to be baptized. Although Nadia Bolz-Weber may not be for everyone, she does a bang-up job of reminding us that the gospel is truly for all sinners and saints.