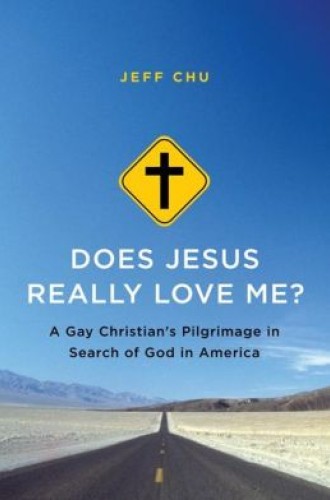

Does Jesus Really Love Me? by Jeff Chu

Religious book publishers have brought out scores of titles about homosexuality in recent years, but Jeff Chu’s book is in a class of its own. A gay Christian with a compelling personal story, Chu also happens to be a superb journalist who listens closely to whoever is sitting across from him. “When I first came out, I couldn’t find a book with stories across a theological and experiential spectrum,” he says. So he spent a year traveling the country and talking with dozens of people with a wide range of perspectives. Along the way, his project became a spiritual pilgrimage.

Chu deserves the broadest possible audience, not just because of his subject but because he shows how to charitably engage believers who hold very different views. This is a good strategy, of course, for it models the kind of understanding he wants in return. It also makes for lively reading. We sit on the edge of our seat as he meets with Richard Land, top lobbyist for the Southern Baptist Convention, “large, imposing, not a little loud, not a lot subtle, unapologetically political,” who accuses homosexuals of causing the “full-blown paganization” of America. Another firebrand southern pastor tells Chu why homosexuality is “the biggest threat to our civilization!” (Apparently they had no idea he is gay.)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Likewise, Chu finds drama in a range of people coming to terms with their sexuality whose experiences differ from his. He visits with three gay men who have fallen from belief, and another who has left pastoral ministry to become a sous-chef. A middle-aged man in Minnesota tells him why he has chosen to remain celibate. A woman in Seattle claims to have been “healed” of lesbian desires: “Some people will believe this, and some people won’t,” she says. “That’s okay. This is my story.”

Chu is willing to accept that many different experiences are at some level authentic. When a gay man and a straight woman awkwardly insist that they are determined to make their marriage work, Chu charitably notes:

It’s difficult for me, as a gay man, to hear my sexuality described as a wound, as an imperfection. Yet I understand that this is how Jake sees it—how he must see it, given his worldview. . . . It’s tempting to say, “Wow, he’s repressed.” And yet hear the long version, sit with them, listen to their struggle, understand the incredible work they’ve done to unpack and analyze and process and reevaluate, and things look different.

In the light of these conversations, Chu does some serious soul-searching and reexamines his own hard-won beliefs, as indicated by the book’s questioning title.

Chu’s own story by itself would have made for a strong, though lesser, book. Raised in a strict Baptist household, the grandson of a pastor, he attended a Christian high school where the fate of an outed teacher let him know what lay in store if he revealed his own feelings. His parents still have not accepted his sexuality. Songs from childhood resonate with him—“Jesus Loves Me,” of course—but it has been hard for him to find a church where he feels both accepted and fulfilled, for he is an evangelical at heart, restless amid liberal platitudes. Metropolitan Community Churches, he feels, are more preoccupied with sexual identity than with God. At Highlands Church in Denver, he finds a more diverse, God-centered family of faith. In the course of writing his book, Chu becomes a mentor to a young gay Christian whose own strength of spirit inspires him.

All of this personal experience provides context for Chu’s journalism. In largely evangelical Nashville, a pastor explains how his megachurch has decided to help a lesbian couple raise their child in the faith, and a young lesbian woman describes her journey to vital Christianity. A counselor in Memphis who formerly tried to help people “leave the gay lifestyle” now admits that “things I’ve taught have been wounding.” The country’s rapid movement toward new views is reflected in such fascinating profiles.

Chu grants most of his subjects a sympathetic hearing, but at times he is willing to give them plenty of rope, as he does with disgraced pastor Ted Haggard, still defensive and opaque, and Alan Chambers, longtime president of the ex-gay organization Exodus International, who vainly tries to explain what he means by the slogan “Change Is Possible.” (Since publication of Chu’s book, Chambers has apologized for his part in the promotion of discredited orientation-change therapies.)

Showing incredible pluck, Chu goes where few other gay men would dare to go—Westboro Baptist Church of Topeka, Kansas, which famously proclaims that “God Hates Fags.” Baked by hellish 105-degree heat, he meets a six-year-old boy wearing a placard that bears those words. Chu’s face-to-face meeting with the Reverend Fred Phelps seems like an encounter with pure evil:

Slouched in an office chair behind his desk, his skin sallow, Phelps looks all of his eighty-two years. His frosty eyes, peeking out from the brim of his white cowboy hat, are several shades paler than the blue of his Kansas Jayhawks jacket, which seems to protect him from his own chill.

There’s an uncanny moment when Chu briefly wins Phelps over with a scrap of biblical quotation and mention that his grandfather was a Baptist preacher. “I think we might be able to have a little bit of friendship,” Phelps says.

At times Chu’s effort to understand such a hateful figure strains credulity. Noting Phelps’s early fame for his work for racial justice and the honors he received from the NAACP, Chu briefly wonders if this might be a modern-day John Brown. He marvels at the ordinary good manners of Westboro members who offer him pizza and a soft drink. “Every member of the church we meet, except for Fred, is warm and welcoming. They’re good, easy conversationalists,” he writes. “And they can be charmingly self-deprecating.” “What if they’re right?” he muses. “Maybe they’re right.” If the book has a flaw, it is this plaster saintliness.

Twenty years ago, Mel White surprised many people when he left the employ of Pat Robertson and Billy Graham and came out. It may be a measure of the distance we’ve traveled that he is not even mentioned in Chu’s book. Instead, we hear from Andrew Freeman, a gay pastor who has found welcome in the Episcopal Church but can’t wait to move on to another topic. “Sitting around and talking about whether God actually loves gay people is quite uninteresting,” he says. “There are far more important things in our faith to discuss, and far more important work that our faith requires of us.” The question mark in Chu’s book title might well be traded for an exclamation point.