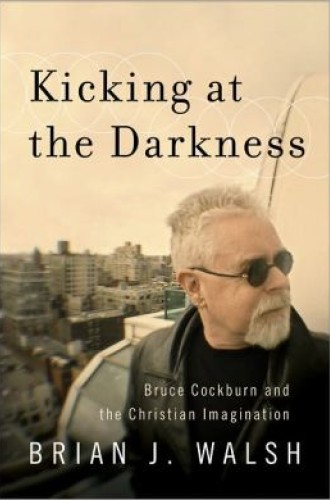

Kicking at the Darkness, by Brian J. Walsh

Some of us owe a large part of whatever prophetic imagination we have to the creative powers of Bruce Cockburn. For pop-music-loving Bible readers of my generation, chances are he came to us via U2 of the late 1980s. In “God Part II,” from Rattle and Hum (1988), Bono tells of a late-night radio singer announcing his resolve to “kick the darkness / Till it bleeds daylight.” Liner-note readers like myself found next to this devastatingly evocative phrase a footnote introducing Cockburn, from whose “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” the line was purloined. From there I’m guessing sales of the Canadian bard’s albums—he’d been putting them out since 1970—spiked more than a little.

By that point, Brian Walsh, Christian Reformed chaplain to the University of Toronto, was already a devotee of Cockburn’s work. In his own theological engagement with our times, Walsh has never missed an opportunity to weave in Cockburn’s imagery. In this sense, Kicking at the Darkness exemplifies the “deep listening” and “deep receptivity” that Walsh attributes to Cockburn. It offers a powerfully articulate and thorough account of Cockburn’s theological vision. In the process, Walsh makes movingly explicit his debts to the singer’s albums and performances with regard to his own living, thinking and writing.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Looking hard at the world with Cockburn, Walsh believes that we begin to see the glory of God told in the heavens above and beneath our feet when we respond to “the gratuitous givenness” (Norman Wirzba’s phrase) of the natural universe. The sacramental insight of seeing nature as gift, as Walsh persuasively argues (with Sylvia Keesmaat) in Colossians Remixed, is central to the good news that the apostle Paul provocatively insisted has been somehow mysteriously and consistently proclaimed to every creature in the cosmos (Col. 1:21–23). Or as Walsh puts it, “Wherever there is life there is witness to this God.”

As a contemporary seer taking in and taking to heart the “creational eloquence” of our sweet old world, Cockburn offers “songs of reorientation” that call us to revel in and get in sync with the staggeringly beautiful dance of creatures, forests, oceans and deserts (“Lord of the Starfields,” “Great Big Love,” “When You Give It Away”), while lyrically decrying the seemingly endless desecration of all we’ve been given to steward and cultivate (“The Trouble with Normal,” “If a Tree Falls,” “More Not More”). In keeping with a robust theology of embodiment, every image of sin and salvation is inescapably social. The possibility of reorientation and restoration can be sought only in the daily life we’re in.

Walsh renders a deep and enlivening service by placing Cockburn in the company of the prophets. Situated with the likes of Dorothy Day, Hildegard of Bingen, Frederick Douglass and Daniel Berrigan, Cockburn sketches a world in which the alleged maintainers of public order are shown to be the hapless enforcers of institutionalized disorder. Alive to the alarming extent to which we become inured to the socialized insanities of the status quo, a song like “Beautiful Creatures,” from Life Short Call Now (2006), explores the fashion in which we bind ourselves to habits of casual destruction, betraying the hope of human thriving. Cockburn looks hard at what our activities yield for people on the wrong end of “everyday low prices,” as well as for future generations who inherit our concrete meadows.

By way of Cockburn, Walsh insists that these explorations are eminently theological. They have to do with our relationship to God and with our good or bad religion. In his evocation of more than one minor prophet, Walsh argues that our knowledge of God can be discerned in our everyday liturgies. And more darkly, some behaviors seem to preempt the possibility of seeing God at all: “Their deeds do not permit them to return to their God” (Hos. 5:4). Cockburn’s “Broken Wheel,” from Inner City Front (1981), assures us of God’s mercies but also offers a candidly eschatological consideration of what a genuinely biblical grace might look like in view of our complicated histories: “The word mercy’s going to have a new meaning / When we are judged by the children of our slaves.”

How might our talk of God’s amazing grace be most faithfully revised when we take into account our complicity in various forms of what Cockburn refers to as “parasitic greedhead scam”? Have we begun to consider these matters in our understanding of our own worship? Walsh puts these questions squarely before us.

A couple of quibbles: First, my fondness for Walsh’s prose had me occasionally wishing he would quote lyrics a little less and elaborate on them a little more.

Second, Walsh is understandably determined to argue that Christians should pay heed to Cockburn as one of their own: “In a culture that has lost its imagination we need new dreams. Bruce Cockburn awakens such an imagination. And it is a Christian imagination.” But he might have put it less exclusively. I take Cockburn to be (like Patti Smith, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash and Nick Cave) one of our greatest lyrical readers of scripture, but his own debts appear to be more religiously pluralistic than Walsh’s treatment lets on. And as Walsh’s own reading of Colossians might suggest and Cockburn’s comprehensive vision implies, the magnanimous God made known in Jesus of Nazareth isn’t limited to the confines of what we take to be our traditions. To put it differently, the good news proclaimed to every creature (common grace?) takes myriad forms, and the work whereby God is reconciling the world to God’s self defies our powers of category. In any case, Walsh is careful to draw a line between his interpretation of what Cockburn’s up to and the man’s own convictions.

The care and wit with which Walsh interprets songs is a profound grace to Cockburn and his listeners. The book describes only the tip of the iceberg in terms of Cockburn’s output. As an introduction to him, it is indispensable.