Blessed and dangerous

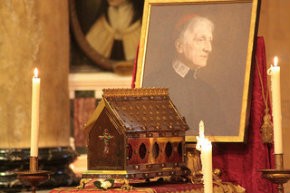

What might be called the year of John Henry Newman has come and gone with a flurry of books devoted to the former cardinal. His beatification—the last stage before granting full sainthood—was conferred by Pope Benedict XVI in September 2011 at an outdoor ceremony in Birmingham, the city where, from 1848 until his death in 1889, Newman did most of his work after becoming the most famous convert to Roman Catholicism in the 19th century.

The prospect of Newman’s being raised to the altars as the Blessed John Henry has not pleased all Catholics. Garry Wills called Benedict “a dissembler and disguiser” for praising Newman as “a model of submission to church authority.” For Wills, Newman was a testy rebel against Vatican obfuscation and authoritarianism until, in 1881, the newly consecrated Pope Leo XIII “bought him off with a cardinal’s robes when he was eighty and tamable.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The recent spate of books on Newman shows that there is little hope of settling all arguments about Newman or about Benedict’s understanding of him. Yet one matter can be set straight: Newman’s entry into the Church of Rome hardly turned him into a lapdog of the Roman curia. One 19th-century Vatican monsignor was quite alarmed by Newman’s alleged “radicalism”—his stress on the primacy and inviolability of conscience, his insistence on fairly viewing all sides of a controversy, his open criticism of the papacy, his argument that Christian doctrine is not ahistorically fixed but historically developing. These accumulated “heresies” prompted the prelate to call Newman “the most dangerous man in England.” He also recommended that Newman be “crushed.”

It is our great good fortune that Newman was not squashed. Gerard Manley Hopkins and James Joyce regarded him as the greatest prose master of the 19th century. Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua is increasingly honored as the most important spiritual autobiography since Augustine’s Confessions. His work is also as wide as it is deep: hundreds of sermons, many hymns (including “Lead, Kindly Light”), a remarkable poem (“The Dream of Gerontius,” splendidly set to music by Edward Elgar), several works of history as well as fiction, but perhaps most especially his treatises on education, theology and philosophy: The Idea of a University, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine and Grammar of Assent.

All three books reveal a figure to be taken even more seriously now than in the past, a beatified iconoclast who still remains dangerous even as he is being canonized.

He is also in many ways a contemporary thinker, not an outmoded Victorian. He stands near to Kierkegaard, for example, in his searing critique of state-established Anglicanism as a bourgeois culture-religion, a bland and innocuous faith that was headed, inevitably, toward the atheism that the great Dane found incipient in the Christendom of 19th-century Germany and Scandinavia. He was not far from Nietzsche, at least in this passage where he stares straight into Nothingness: “If I looked into a mirror, and did not see my face, I should have the same sort of feeling which actually comes upon me, when I look into this living busy world, and see no reflection of its Creator. . . . Either there is no Creator, or this living society of men is in a true sense discarded from His presence.”

Like Wittgenstein, Newman did not think that reason provides absolutely certain answers to life’s most important questions. He believed, instead, that we think and act within a complex web of proximate truths—including Christian truths—and that these cumulative probabilities are sufficient to require us to believe and be bound to them.

He was not frightened by Darwin, declaring that evolution seemed self-evident. It would be strange, he wrote, “that monkeys could be so like men, with no historical connection between them, as that there should be no course of facts by which fossil bones got into rocks.” Rather than fleeing from the Victorian obsession with historical inquiry, Newman welcomed it.

Like today’s postmodernists, he insisted that there is no value-neutral, eagle-aerie “view from nowhere.” We perceive and judge things from the perspective of our own era and place. Far from regarding such a stance as inimical to Christian affirmation, Newman discerned a deep accord between historical particularism and the historical character of Christianity itself.

The rub comes, of course, with Newman’s argument that the utterly unknowable God makes himself definitively known in the historical realities of Christ and his church. Far from being desiccated intellectual propositions, the church’s dogmas are the very source of its life. The church’s living tradition ensures that its doctrines do not become fixed and static.

Embracing evolutionary change and historical development, Newman argued that the vitality of dogma lies in its constant deepening and enlargement. Christian doctrine remains true to itself precisely by way of its organic growth. The acorn of Christian revelation continues to ramify into the great oak tree of the creeds and articles of faith. What is originally embryonic undergoes constant maturation. The church thus excavates the depths of the deposit of faith, endlessly mining its riches in order that the gold of the gospel might burn ever more brightly.

Edward Short shows how Newman engaged the literary and theological culture of his time. He offers chapters on Newman’s extended encounters with two high-church Anglicans whom he failed to bring over to Rome, John Keble and Edward Pusey; with several eminent Victorian women who sought his counsel, including Emily Bowles, Lady Chatterton and Catherine Ward; with such leading literary lights as Matthew Arnold, William Makepeace Thackeray and Arthur Hugh Clough; as well as with one of Britain’s most notable prime ministers, William Gladstone.

The reach of Newman’s broad and deep influence was due, in no small part, to the magniloquence of his prose. Short argues that Newman does not seek to display his syntactic virtuosity so much as he verbally bodies forth his unique vision and voice—as in this meandering periodic sentence from his autobiography, where he alternates long Latinate words with crisp Anglo-Saxon monosyllables so as to offer the equal of anything Henry James ever penned:

The throng and succession of ideas, thoughts, feelings, imaginations, aspirations, which pass within [the man of genius], the abstractions, the juxtapositions, the comparisons, the discriminations, the conceptions, which are so original in him, his views of external things, his judgments upon life, manners, and history, the exercises of his wit, of his humour, of his depth, of his sagacity, all these innumerable and incessant creations, the very pulsation and throbbing of his intellect, does he image forth, to all does he give utterance, in a corresponding language, which is as multiform as this mental action itself and analogous to it, the faithful expression of his intense personality, attending on his own inward world of thought as its very shadow.

Ignatius Press is to be commended for reprinting Erich Przywara’s excellent synthesis of Newman’s thought in a single volume, gathering representative excerpts under such topics as “God,” “Preparations for Christianity” and “Miracles.” It’s not difficult to discern why this great Silesian Jesuit should have been drawn to Newman at the same time that he served as Karl Barth’s chief opponent in the battle over the natural knowledge of God—a debate that continues to be agitated in our time.

This particular gem reveals why Barth would have recoiled from Newman, for it trumpets Newman’s affirmation of the analogia entis, the argument for God from the nature of being itself: “The mystical and sacramental principle,” Newman discovered, is “that the exterior world, physical and historical, was but the manifestation to our senses of realities greater than itself. Nature was a parable; Scripture was an allegory; pagan literature, philosophy, and mythology, properly understood, were but a preparation for the Gospel.”

John Cornwell has produced a most engaging and provocative book on Newman. A somewhat disaffected Catholic (who once prepared for the priesthood), Cornwell is the author of Hitler’s Pope, a vitriolic attack on Pope Pius XII for allegedly legitimating the Nazi regime by pursuing a Reichskonkordat with the German state in 1933.

Cornwell is determined to knock askew any halo hovering over Newman. He is virtually obsessed, for instance, with Newman’s relation to his fellow priest and longtime companion Ambrose St. John. That the pale and somewhat effeminate Newman ordered St. John to be buried alongside him is sure proof, for Cornwell, that their relation was homosexual, though he concedes that it was spiritually sublimated rather than physically consummated.

Cornwell also scorns what he calls “the cult of [Newman’s] beatification” by pointing out that the putative saint was often unsaintly; indeed, he could be waspish, cunning, equivocating, self-absorbed. Yet there is no need for Cornwell to replace the odor of sanctity with the whiff of scandal. Newman himself confessed his own unworthiness: “I have nothing of the saint about me as everyone knows.”

Nevertheless, Cornwell is much to be admired for dealing openly with what remains most “dangerous” about Newman—namely, his antiliberalism. When he was made a cardinal in 1881, Newman declared that his entire life’s work, as an Anglican no less than as a Roman Catholic, had constituted an unremitting “struggle against liberalism in religion.” It is the “great mischief” of the modern age, he said, “an error overspreading, as a snare, the whole earth.” Tolerance is another word for indifference, according to Newman, since in the modern world any one religion is held to be as good as any other—indeed, as satisfactory as no religion at all. Liberalism is “the anti-dogmatic principle,” as Newman succinctly put it.

Liberalism entails, for Newman, a deadly disregard for truth, especially the truth revealed in Jesus Christ and his church. As Newman declared in the Biglietto speech of 1881, liberalism holds that Christian revelation “is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact, nor miraculous; and it is the right of each individual to make it say just what it strikes his fancy.”

In what remains perhaps the best place for neophytes to begin reading Newman, “The Tamworth Reading Room Letters,” Newman defines liberalism as “the mistake of subjecting to human judgment those revealed doctrines which are in their nature beyond and independent of it, and of claiming to determine on intrinsic grounds the truth and value of propositions which rest for their reception simply on the external authority of the Divine Word.”

Newman never denied that there are basic beliefs and fundamental assumptions other than those revealed and developed in the church. What troubled him, as Cornwell points out, is that first principles have been reduced to what Newman called “private judgment.” They are regarded as virtual aesthetic preferences that can be taken up or laid aside without consequence. Hence Cornwell’s crucial quotation from Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine:

That truth and falsehood in religion are but matters of opinion; that one doctrine is as good as another; that the Governor of the world does not intend that we should gain the truth; that there is no truth; that we are not more acceptable to God by believing this than by believing that; that no one is answerable for his opinions; . . . that it is enough if we sincerely hold what we profess; that our merit lies in seeking, not in possessing; that it is a duty to follow what seems to us true, without fear lest it should not be true; . . . that belief belongs to the mere intellect, not the heart also; that we may safely trust to ourselves in matters of Faith, and need no other guide.

Questions of the utmost moral and religious importance, Newman laments, have been reduced to matters of mere prejudice, since they cannot be adjudicated by any ultimate authority. Hence this crucial complaint in his autobiography: “There is no existing authority on earth competent to interfere with the liberty of individuals in reasoning and judging for themselves. . . . There are rights of conscience such, that every one may lawfully advance a claim to profess and teach what is false and wrong in matters religious, social, and moral, provided that to his private conscience it seems absolutely true and right.”

Taken out of context, Newman could be made into an authoritarian advocate of absolute truth wielded by brutally repressive regimes. Instead, he offers a radical alternative to both the theocratic right and the atheistic left. For him, our moral sense is never merely private. It becomes personal and individual because it is already and always universal and communal.

Conscience in that sense was for him the essential principle of all religion. While a debased conscience asserts private will and desire, true conscience provides an inner voice, a moral echo, a spiritual reverberation of something that is exterior and superior to us. It establishes a relation, said Newman, “to an excellence which it does not possess, and a tribunal over which it has no power.”

Newman does not regard conscience as offering specific distinctions about good and evil, nor does it instill a vague guilty-making sense of duty. As Cornwell explains, conscience for Newman is “comparable to our possession of reason, memory, and the perception of the beautiful.” It is “the voice of God” quite apart from our will or desires. This “law of the mind” provides, instead, “an underlying conviction that we ought to do what is right and avoid what is wrong.” To obey conscience—as Gaudium et Spes would declare, in a Newmanesque moment during the Second Vatican Council—“is the very dignity of man. . . . There he is alone with God, Whose voice echoes in his depths.”

Cornwell makes it clear that conscience does not mean, for Newman, what it has come to mean in our time: an unassailable citadel of privacy, sincerity and authenticity. Nor can conscience be reduced to an all-determining “peace of mind.” Autonomous conscience of this kind becomes the truth-denying fortress of subjectivism. Newman teaches, on the contrary, that conscience is either well or ill formed. Its formation creates, in turn, a certain kind of character that predisposes us either toward or against both faith and morality. We must want to trust and obey. Belief and unbelief are matters of the heart more than the intellect.

Christian faith, it follows, is a matter of lifelong conversion, a gradual reconstitution of body and soul alike, a slow transformation akin to what the ancient church called theosis or deification. In The Idea of a University, Newman reveals his own prescription for both the intellectual and the religious life: “I should not rely on sudden, startling effects, but on the slow, silent, penetrating, overpowering effects of patience, steadiness, routine, and perseverance.”

In Newman’s novel Loss and Gain, a character vividly describes the kind of person that rightly shaped conscience is meant to produce: “A man’s moral self is concentrated in each moment of his life; it lives in the tips of his fingers, and the springs of his insteps.”

These calls to thoroughgoing Christian formation are especially germane in a time such as ours. Many evangelicals have hailed a virally popular video trumpeting the message that “Jesus came to abolish religion.” In a similar vein, the Easter issue of Newsweek featured Andrew Sullivan urging readers to “Forget the Church, Follow Jesus.” Sullivan sounds rather like the deistic Benjamin Franklin summoning Americans to imitate Thomas Jefferson and Francis of Assisi. Jefferson followed “the purest, simplest, apolitical Christianity,” according to Sullivan. And, as if St. Francis were a churchless saint who went about doing good, Sullivan hails the saint for foreswearing all power over others. Hence Sullivan’s call for American Christians to seek “truth without the expectation of resolution, simply living each day doing what we can to fulfill God’s will.”

Cornwell demonstrates that Newman would have derided these calls for an individualistic, moralistic and creedless Christianity. Life in Christ is grounded and sustained, Newman insisted, in and through the life of the church—strumpet Bride of Christ though she often is. Radical human transfiguration is the consequence, writes Cornwell in summarizing Newman, “of encountering the Christian religion, its people, its objects, and its practices over time. . . . [It] involves imaginative apprehensions of its prayers and sacraments, its rituals and Scriptures, its Creed, and all the tangible, visual and concrete expressions of Christian faith. Above all it involves the presence of Jesus Christ in our imaginations, in the Eucharist, and in the community of the Church.”

Christians do not make truthful witness to the world, Newman teaches, by seeking to occupy neutral ground via secular arguments about rights. He calls us, instead, to reimagine the gospel in fresh moral and spiritual terms. He reminds us that Christianity is a public and political faith because it is first and last an ecclesial faith. He clarifies the ethical and doctrinal claims that have been revealed and developed in the bimillenary history of the church. He engages the imaginations of all people of conscience, challenging and transforming the smug preconceptions of Christians and unbelievers alike. In so doing, he remains the dangerously Blessed John Henry Newman.