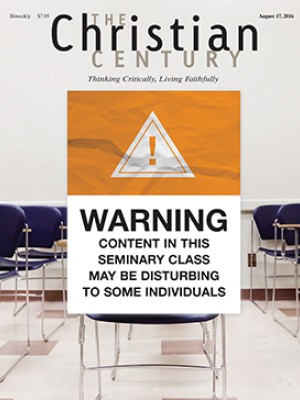

When learning hurts: Content warnings in seminary classrooms

Theological educators don't just teach a particular kind of content. We also model a process for engaging with sensitive issues.

The first class I ever taught to seminary students was about death. I was a graduate student myself at the time. I’m not sure why I picked that topic among the various subjects in a course on pastoral care, but I remember I had a well-prepared lesson plan, including an opening lecture.

As I was speaking, I noticed that John, a student in the front row who was usually very engaged in class, was slumped down in his seat. He didn’t make eye contact with me even when I asked questions.

When the class took a break halfway through the session, I realized that a group had gathered around John. He was sobbing uncontrollably, and others were trying to comfort him. I had no idea how to respond, but the professor who oversaw the class went over to talk with him. After a brief conversation John left the room. He returned about 15 minutes later, after the class had reconvened, and seemed more at ease.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I learned later that John’s brother had been murdered the year before. He had thought he would be able to make it through class that day, but when I began talking about grief and mourning he had been overwhelmed by emotions. He did not know what to do, so he just stayed in the classroom, becoming more and more distressed—until he finally broke down.

Over the following weeks the class continued to take up topics such as abuse, family violence, and addiction, which could be emotionally charged for people. I noticed how the professor would begin class by acknowledging that the topic for the day might touch students personally and saying that they should feel free to leave the classroom to collect themselves if they needed to. If I had known enough to make a similar comment in my class, I might have made it easier for John to deal with his feelings that day.

The practice of alerting students to the possibility that a topic might trigger deep emotions—giving them a “trigger warning”—has become widespread, but it is also the subject of controversy. It’s not always clear what topics will be disturbing to students or how much teachers should do to prepare them.

Writing last year in the Atlantic, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt worried about a movement seemingly designed to “scrub campuses clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense” (“The Coddling of the American Mind”). A recent study conducted by the National Coalition Against Censorship, which is skeptical of trigger warnings, reported that students have objected to many different elements of course materials, including depictions of rape, nudity, homoeroticism, images of dead bodies, or foul language. Does student insistence on trigger warnings reflect a resistance to dealing with difficult topics? Might the concern to protect students’ feelings lead teachers to provide less challenging or less controversial materials? Doesn’t learning involve a level of risk and discomfort?

As a teacher I seek both to challenge students to confront difficult subjects and to provide a safe space for learning to happen. Theological educators bring a special perspective to the discussion of content warnings, for in training people for ministry we are not only teaching a particular kind of content; we are also modeling a process for engaging with sensitive issues that we hope students will draw on in their own ministries.

For instance, when seminaries teach biblical exegesis, they not only want students to learn the critical skills needed to read the Bible responsibly. They also want students to understand the nature of the interpretive process so that they can offer guidance to others who seek to do faithful biblical interpretation in their own contexts. Historically, mainline Protestant schools have been committed to presenting academic material that may be disruptive to students’ beliefs and faith traditions. The historical-critical methods of interpreting the Bible are often profoundly challenging to students who come to seminary with more literal understandings of scripture. We do not excuse students from encountering this challenging material; rather, we urge them to integrate what they are learning in the classroom with the faith that makes them who they are. Asking hard questions about faith and learning how to respond to those questions is part of theological education.

Ever since my classroom experience with John, I have followed my professor’s lead: I alert students ahead of time to the nature of the material we will study and encourage them to tend to themselves appropriately. But I don’t excuse students from encountering the material.

My colleagues in other disciplines tend to take a similar approach. I know a church historian who once had a student walk out of class during a lecture about the slave trade because he found the details too difficult to hear. Up to that point, the student had always thought about the slave trade as just history; he was unprepared for the effect this material would have on him. Since that time, my colleague has introduced the material so that students will know what’s coming and why it is important to encounter it. She says, “I rarely shy away from making sure that students are fully aware that Christians have been killing Christians for centuries, and inviting them to think both historically and theologically about that reality.”

A colleague who teaches Old Testament says he too takes the time to prepare students for difficult material, such as the violent sexual imagery in the books of Hosea and Ezekiel. He will even add a note to the assignment on reading Ezekiel 16 and 23–24: “A warning: these are difficult, even offensive passages, dealing particularly with violence and rape.”

Educators often know the issues for which students need some additional preparation. In my classes, I often know some of the specific issues that students are dealing with, having early on assigned papers that ask them to describe and reflect on personal experiences. Every term I generally have at least one student who is a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, and I frequently have students who have suffered a major loss. Some of them have personally experienced rape or other types of violence. I feel I have a pastoral obligation at least to alert them when the course will cover such material.

I am also trying to train students to be reflective practitioners. I want them to be aware about what they bring from their own experience to the practice of ministry. It is important for them to be able to recognize when their own experience shapes their ministry—both how that experience is useful and how it can get in the way. It’s also important for them to know what is happening inside them during the caregiving moment. As they grow in self-awareness, they will grow in their ability fully to attend to other people.

Asking students to tend to themselves during difficult class sessions is not a form of indulgence; it is a way of helping them to practice the self-awareness that is critical in ministry. This kind of reflection can help students to recognize areas where they need additional emotional or psychological support. In some cases, it may even help them discern that pastoral ministry isn’t their proper calling.

I remember one class in which students were required to map their family tree and analyze family dynamics, exploring their family’s various strengths and limitations. The assignment was designed to help students reflect on what they bring from their family background that might help or hinder them in ministry.

One student turned in a paper that described a perfect family, with many different strengths and no negative aspects at all. The professor directed the student to rewrite it so as to provide a more honest assessment. After all, no family is perfect. The student replied that he would rather receive a zero on the paper than do that—that’s how painful it would be for him to engage the truth about his family. The professor asked the student to consider whether, given his reluctance to engage his own personal experience, ministry was the right path for him.

I want to make the classroom safe not in order to protect students from issues but to provide a place for them to process issues and acknowledge vulnerability. Only by acknowledging one’s vulnerability can one become a skilled caregiver.

One of the most powerful learning moments I have witnessed as a teacher came about because the classroom was safe enough for vulnerability. In a class about violence between intimate partners, a male student asked, “Aren’t abusive tendencies already obvious at the beginning of a relationship?” A female student responded by sharing her experience of enduring an abusive marriage for more than 20 years. She explained that her husband’s abusive qualities had not been apparent at first. In fact, he had been extremely charming and kind during their courtship. The man who had raised the question thanked the woman for the depth of her sharing and for helping him better understand abuse.

This learning moment was possible because of the female student’s courage and the male student’s openness to listening to her story. If either of these students had feared being attacked, either for raising a question or for responding honestly to it, the learning would not have taken place.

Making the classroom a safe space for dialogue and disagreement doesn’t mean that no one is ever going to get hurt. In fact, ironically, the only way to make classrooms safe for real engagement is to open up the possibility that people will get hurt. This is why it is crucial also to foster a climate of repair in the classroom. Even when norms for respectful conversation are in place, people will make mistakes and will need to ask each other for forgiveness at times. If students are too fearful of saying the “wrong thing,” they may hold back in their conversation. If this happens, the group may avoid some moments of discomfort, but at the cost of missing out on moments of deep learning.

Finding and maintaining the right balance between safety and challenge is important not only for the immediate context of the classroom, but for helping people learn to do ministry. Students at my seminary will be part of faith communities that are struggling to address issues of sexuality, racial tension, and environmental crisis. Faith communities that aren’t safe enough for people to be vulnerable will lack authenticity. Such communities may be free of open conflict, but they will probably also be free of real, deep intimacy. When faith communities are completely free of discomfort or challenge, they may become stagnant, and they will find it difficult to follow where God leads.

Some people might say that classroom warnings are just a way of coddling students and allowing them to avoid responsibility for their own learning. I think the opposite is true. By alerting students that we will be dealing with tough issues, I acknowledge that they are not just disembodied brains, but whole people. Some topics will touch them deeply.

Warnings are a way of inviting students to take responsibility for their own well-being in the context of learning. They are a way of helping make the classroom safe enough to risk vulnerability, rather than pretending that the subject is only the occasion for an intellectual exercise. They are a way of showing students that what we are doing together matters and has the potential to push all of us beyond our comfort zones into a place where deep learning can happen.