Being they: God and nonbinary gender

We call God "Father" and "Mother" because children don't say "Parent, Parent." But what will my children call me?

This year Pilgrim Press published my first book. Like any new author, I was overjoyed to be done. But one thing made me especially proud: as far as I know, Glorify: Reclaiming the Heart of Progressive Christianity is the first book published by a major church press to deliberately use gender-neutral pronouns throughout.

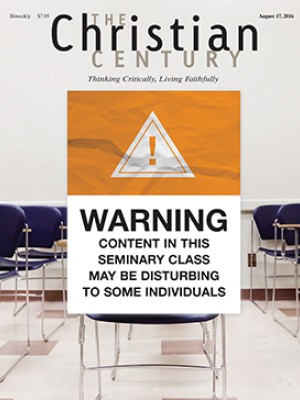

My use of the singular they, them, and their triggered some copyediting anxiety at first. I get that. I was an English major, and I was taught always to write “he or she” when I wanted to be gender inclusive. Besides, Glorify is not a book about gender theory. It’s a book calling mainline churches back to the task of cultivating Christian disciples. It seems like an odd place to make a stand for a nonbinary understanding of gender.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But for me, this was personal.

When I fly somewhere, I walk into the airport already on high alert. It’s not the flight itself that bothers me; it’s the Transportation Security Administration. TSA security screening is an inherently gendered process. While you are stepping into the machine and raising your arms over your head, a TSA agent is pressing one of two buttons: blue or pink.

If your gender presentation clearly aligns with your birth sex, this isn’t generally an issue. The only anomaly your scan is likely to show is something like a forgotten passport in your hip pocket, leading to a couple of quick questions before you’re on your way. But if you are transgender, genderqueer or gender nonconforming, the scan is the start of a long, often invasive process. I always get “blue boxed.” That’s what I call it when they see me coming and press the blue button. Because I was born female, a bunch of “anomalies” are detected—and as soon as I’m through the scanner a male agent is patting me down. I have to tell the agents to press the pink button and send me back through.

Of course, the pink button doesn’t fit me either. I identify as genderqueer or gender nonconforming. While I am comfortable living in a female body, I present in a typically masculine manner. This makes encounters with the TSA unpleasant and embarrassing. It also makes something as mundane as a visit to a public restroom potentially dangerous.

Our culture teaches us to see gender as a binary and closely correlated to our sex at birth. In recent years we have come to understand that some individuals transition from their birth sex and live life as the opposite sex. This increased awareness of trans experience is a wonderful thing. Churches are growing in their understanding of MTF (male-to-female) and FTM (female-to-male) individuals, including children and youth, and developing resources to support them in their transitions. We need to keep doing that.

But what about those of us whose gender falls outside the binary? What about those of us who embrace our gender identity not through name changes, hormones, or surgery, but through other means?

The phenomenon of being genderqueer is not new. The Hebrew sacred writings have distinct words for as many as six different genders. Some Native American cultures have long recognized “two spirit” individuals who possess both masculine and feminine traits. A variety of other cultures have as well.

None of this helped me much growing up in the American South in the 1980s and ’90s. All I knew is that, at my core, I was not like the rest of the girls. But I wasn’t a boy, either. And it went beyond being a tomboy or not liking dresses; it was much deeper than that.

As I wrestled with gender in my twenties, there was one thing that did a lot to help me understand myself: my theological training.

I was trained as a Reformed systematic theologian, and what I remember more than anything else from that training is this: God is God. It’s a Barthian way of saying that no matter what images or descriptions we assign to God, they will always be inadequate. God is always more than that, and to say otherwise is idolatrous.

What does this mean for God’s gender? If God is not “he,” then saying that God is “she” is no more accurate. I once asked a theology professor of mine why we didn’t just use exclusively gender-neutral terms to describe God. He responded, “Well, because we don’t say ‘Parent, Parent.’”

He’s right. Most of us have called parents “Mom” or “Dad.” But when my professor said that, I immediately wondered what my future children would call me. I also wondered whether a family like mine would have a place in the church. Would people like me be seen for who we are and truly included?

I’m still not sure. Even progressive churches often reinforce the gender binary, however inadvertently. A piece of a liturgy might label different lines for “men” and “women.” An organization might insist on alternating between male and female leadership in a given role, without considering who this excludes. Progressive churches, thinking they are being more inclusive, might swap out the term same-sex marriage for the less-inclusive same-gender marriage. (My wife and I have a same-sex marriage but not a same-gender one.)

It’s all too common to have a conversation about inclusion that fails to bring into the room the people who live exclusion every day of their lives. This often results in well-meaning but careless oversights that take far longer to undo than to implement.

I know this because in the various settings I find myself in I often advocate for more attention to language around gender. So do friends and colleagues of mine who are, or who love someone who is, genderqueer. Often people are polite enough to listen but left without a sense of urgency. I will be the first to admit that genderqueer people are a small minority. But why should small numbers make our concerns irrelevant?

I have prayed to Father God and to Mother God, and I will keep doing so at times. But I’m a person who, as a parent, will identify as neither father nor mother—and I’ve been steeped in the Reformed polemic against idolatry. So I believe there’s another way to describe the parental God as well, one that is not tied to any binary categories but grasps the enormity of God far beyond any human understanding of gender.

If this is true, and if all of us are made in the image of God, then perhaps people like me were created to be exactly as we are: people who transcend binary understanding of gender and live as a reminder of the expansiveness of creation. Maybe that’s a testimony worth making a little time to listen to.