The devil’s beauty

In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the epicurean elder brother Dmitri tells the chaste younger brother Alyosha that beauty is not simply God’s creation. Sodom, he says, was full of beauty when it was destroyed, but its beauty did not save it. Dmitri says, “Did you know that secret? The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious and terrible. God and devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man.”

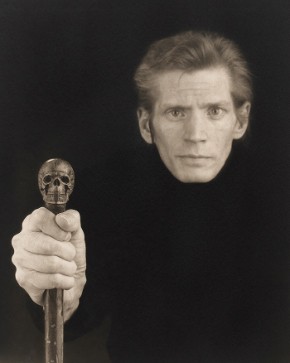

Like Dmitri, photographer Robert Mapplethorpe knew that the beautiful is a battleground, and he was happy to play on the devil’s side. The lasting gift of his work was his ability to tease out the danger in the beautiful.

The J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art are sponsoring a joint retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s work—Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium. The exhibits coincide with Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, an HBO documentary that premiered on television on April 4.