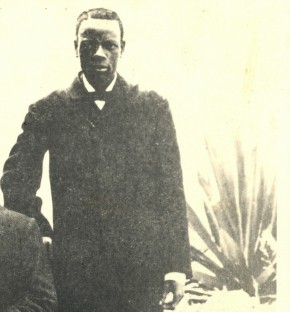

Chilembwe’s rising

A century ago, amid the blood and chaos of the First World War, a period of stunning Christian growth began, especially in Africa. This year, many Africans will commemorate the centennial of a man who perfectly symbolizes that transformation: John Chilembwe.

Notoriously, 1915 marked the beginning of the great massacres and expulsions of ancient Christian communities in the Ottoman realms of the Middle East. Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks all suffered, and Christians were purged from some of the most ancient centers of the faith. But while one Christian heartland was perishing, another was being born.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The vast expansion of Christianity in black Africa is partly due to the withdrawal of European missions. The war itself had a massive and catastrophic impact on African societies as European empires pursued bloody campaigns across vast swathes of the continent, disrupting traditional societies. The war made possible the apocalyptic influenza epidemic of 1918, which killed millions of Africans.

With their long-familiar worlds falling into ruin, Africans naturally sought religious solutions and turned to the prophets and healers who flourished so abundantly. Time and again, when we look at the leaders who would guide new African independent churches through the first half of the century, we see that their move toward active faith occurred precisely during the wartime crises.

Although his career is closely associated with the war, Chilembwe himself belonged to an older generation. He was born around 1870 in Nyasaland, what is now Malawi. In 1889 Nyasaland became a British protectorate, which attracted missionaries like the English Baptist Joseph Booth. Booth held very radical views about African education, self-determination, and even independence, which he shared with his servant John Chilembwe.

In 1897 Chilembwe’s connection with Booth gave him a life-changing opportunity. The two traveled to the United States, where Chilembwe attended the school that is now Virginia University of Lynchburg, a historically black institution. In America, he was inspired by figures like Booker T. Washington. For a thoughtful African appalled by colonial exploitation, visions of black liberation and self-determination were intoxicating, and they continued to develop after he returned to his homeland as an ordained Baptist minister. He became involved in campaigns to safeguard the land rights of native Africans, always a core issue in anti-imperial protests.

The outbreak of war made such grievances still more acute. For the subjects of the British Empire, war brought greater exploitation of colonial territories, more taxes, demands for labor, and pressure to join the armed forces. The war itself came to Nyasaland: 19,000 local men joined Britain’s colonial armies, and 200,000 more served as porters in campaigns in neighboring German East Africa. Chilembwe protested this involvement, complaining that so many Africans were “invited to die for a cause which is not theirs.”

In January 1915 Chilembwe led an open insurrection after the model of John Brown to “strike a blow and die, for our blood will surely mean something at last.” Two hundred rebels attacked local plantations, killing several whites.

Much like the revolt against slavery by John Brown, this rising was an ill-organized fiasco which completely failed to galvanize popular support. Colonial authorities responded savagely, killing Chilembwe and many supporters.

But the failed rising left behind a legacy of nationalist and Africanist sentiment. Chilembwe today is Malawi’s greatest national hero. His face appears on Malawi’s currency, and every January 15 the nation celebrates John Chilembwe Day.

Much about Chilembwe remains uncertain, not least his religious motivation. Almost certainly he was drawing heavily on Baptist apocalyptic ideas as well as on the Watch Tower movement in the United States (later known as Jehovah’s Witnesses), which had identified 1914 as the year of Armageddon. Tragically, his lack of power and status means that few of his own words survive. Some historians see him as inspired much more by nationalism than faith. His rebellion, after all, took as its slogan the war cry, “Africa for the Africans.”

Such nuances obscure the central legacy celebrated by Africa’s independent churches, who claim Chilembwe as a symbol of a new native Christianity, free from its paternalistic and missionary roots. Whatever we make of Chilembwe himself, it is precisely from his time that we can trace the careers of so many other Christian prophets and leaders: of Simon Kimbangu in the Congo, of Engenas Lekganyane in South Africa, and the founders of West Africa’s Aladura healing churches. In 1915, the Christian world turned upside down.