Art and prayer

I’m writing this on an airplane returning from a short trip during which my husband and I visited a Benedictine abbey in northern Scotland and spent time in Oxford with a close friend who is mortally ill. Prayer comes easily in such circumstances; but if St. Paul is right, prayer should be possible in all circumstances.

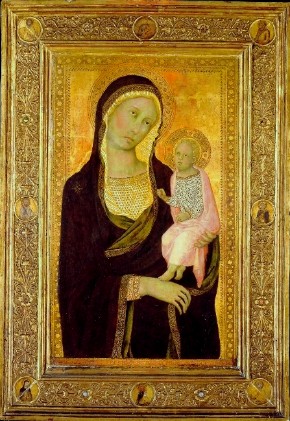

Just before catching the bus to leave Oxford, we spent a few hours at the Ashmolean Museum, where we saw an exquisite little display of late Italian Gothic art, featuring a Virgin and Child by Naddo Ceccarelli and twin roundels of the Angel and Virgin of the Annunciation from the studio of Andrea Orcagna. The accompanying label noted that such objects were originally intended for personal use: “Small devotional images were widely used in the home. They were an aid to private prayer. Their precious materials and refined techniques reflected the glory of God.” Something about this description gives me pause—though the language is appropriate for a historical exhibit, I wonder how many museumgoers take away the impression that Christian image veneration is essentially a thing of the past. Would it have been subversive of me to pray discreetly before these holy images?

On another floor, a gallery of Indian sculptures from AD 600–1900 is interpreted by a maxim from the sixth-century Vishnudharmottara Purana: “The divinity draws near willingly if images are beautiful.” Here amid seated and standing Buddhas and bodhisattvas, wrathful and benign forms of Shiva, noble Jain ascetics, and a cavorting Ganesh, the accompanying notes do manage to link the present to the past: “Images like these remain in worship today throughout India, as well as in the Himalayan region and Southeast Asia, whose cultures were transformed by the spread of Buddhism and Hinduism.” Would it be out of place in a gallery of late Italian Gothic art to mention the continuing relevance for Christian prayer of images like those by Ceccarelli and Orcagna?