What happens when people pray? Anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann

Tanya Luhrmann is best known for her 2012 book When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God, which examines how evangelicals and charismatic Christians experience and communicate with God. A cultural anthropologist, Luhrmann has studied modern-day witches and the assumptions of modern psychiatrists. Her columns appear frequently in the New York Times.

How did you get interested in studying people’s prayer lives?

My first project as a cultural anthropologist was studying well-educated middle-class people in London practicing what they called magic. They experienced divine presence; they saw and heard things. I was flabbergasted.

It turned out that many of the people involved in this practice were reading St. Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises, and the techniques they were using were techniques of prayer.

Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises also come up in your book on charismatic Christianity.

The Ignatian Spiritual Exercises codify and make explicit a set of practices that are common in Christianity and in other faith traditions. Vineyard churches, for example, which want to enable people to find and experience God, have encouraged people to use practices that might be thought of as Catholic.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Ignatius ratchets up the use of the imagination by asking people to enter a particular biblical passage. I did this myself as part of the Vineyard church for about nine months. Each week, we were to spend an hour a day meditating on a passage. With the text on blind Bartimaeus, for example, we were told to wonder: What does he look like? What is his cloak like? What does he smell like? Are you on the road? Part of the crowd? In a tree? Are you blind Bartimaeus yourself?

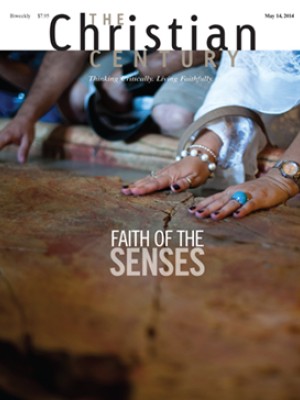

Ignatius asks participants to pay attention to their inner senses—to what they see and hear and smell and taste and touch in their minds. Ignatius says, “I don’t care what the road actually looks like, if it is broad or narrow, if there is a hill or it is flat. I care that you experience something.” These prayer experiences are very powerful.

What would you call a common prayer experience?

Three out of five Americans say they pray every day. The bulk of that prayer appears to be conversational. And people buy prayer manuals, like The Purpose Driven Life, for example, which are descriptions of talking to God in a conversational way.

Have your studies of religious people changed you?

When I started I was focused on whether God was or was not out there. Now I am much more comfortable with ambiguity. I hear people talking about God, and I hear that they are reaching for joy. That’s a project you can get on board with.

I don’t call myself a Christian because that statement has a meaning that is bigger and more dramatic than I feel comfortable making. People will ask, “Have you had a born-again experience?” No, I haven’t had that experience. I grew up in what I would call a Christian family. I would say that over the course of this research I have developed a sense of God. I am still learning about that.

How did you come to write a regular column in the New York Times?

The editors at the Times think religion important, and my voice is different from many of those who speak about religion in their pages. Some people are moved by my columns, some are outraged—such as when I wrote a column that was sympathetic to speaking in tongues.

How do people respond to your attempts to “explain” religious experience?

People’s response to my work depends on whether they have the ability to get outside themselves and be curious about the experience of another human being. To entrenched nonbelievers, it seems I am trying to make imagined beings come to life. To believers, it seems I am reducing religion to psychology. I am trying to do neither.

Can you describe your recent research in Africa and India?

I’ve been comparing the experience of hearing God in Ghana, South India, and the San Francisco Bay Area. I am looking at churches in which people have somewhat similar understandings of God—that God is not only mighty, but intimately accessible, that God is authoritative, but also a person with whom you can have a relationship. These congregations are all English-speaking; they all have college-educated participants. A sermon that is given in one church could more or less be given in another.

In the American setting, where secularism is powerful, people have trouble experiencing God speaking back to them. They have trouble experiencing God’s voice. In West Africa, the supernatural is intermingled with the material world in a way that is very concrete: God gives you money. God has an obligation to respond to you in a concrete way in the here and now. God is almost materially present. God speaks, and people hear. In Chennai, India, the divine or supernatural is still present, but it is much less tied to the material world. There is much less atheism in that context than in America, but the supernatural is less perceptibly real than in the African setting.

What might American clergy learn from your work?

The message for noncharismatic pastors might be that knowing God involves skill. This is not a comment on whether God is real or not real. It is a comment about the fact that you can train human capacities for knowing God. A Christian might say, “God is always speaking.” But why do only some people hear? It might be that some people are paying attention in a way that allows them to hear God more clearly.

The message for charismatic pastors might be that not everyone can have an intimate conversation with God. About a quarter of the people I spoke to in charismatic churches found that difficult to have.