Negative numbers: The decline narrative reaches evangelicals

For most of the latter half of the 20th century, religious life in the United States was marked by four consistent trends: oldline Protestant membership was declining; evangelical Protestants were growing; Roman Catholics were hovering just above the replacement level (with new immigrant growth slightly exceeding the amount of erosion in the white ethnic base); and each succeeding generation of adults was participating less in religious institutions.

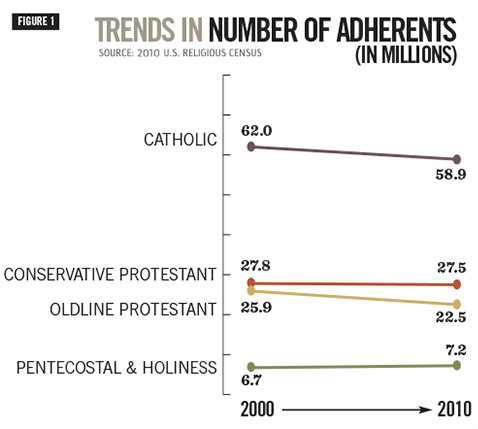

A funny thing happened in the first decade of the 21st century: both Catholics and the conservative wing of evangelical Protestantism joined in the decline (see figure 1). The Pentecostal/holiness family is now the only stream of the Christian tradition that is growing. (This judgment depends on how one categorizes the Latter-day Saints, who are also increasing, and on how one assesses the fortunes of the historically black churches, for which there is not reliable data.) These findings are based on the 2010 U.S. Religious Census data compiled from denominationally provided statistics for 236 religious bodies (available online at thearda.com/RCMS2010).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A more nuanced picture of the decade is provided by data culled from the Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches, which provides relatively consistent annual data on denominations going back to the 1950s (but based on a much smaller sampling than the 2010 U.S. Religious Census compilation). The Yearbook data show that membership growth for the Pentecostal/holiness stream has consistently outpaced that of conservative Protestants since at least 1955. Nevertheless, it peaked during the early 1980s at around 4 percent a year, has slowed ever since, and is currently on the verge of falling below 1 percent a year.

A more nuanced picture of the decade is provided by data culled from the Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches, which provides relatively consistent annual data on denominations going back to the 1950s (but based on a much smaller sampling than the 2010 U.S. Religious Census compilation). The Yearbook data show that membership growth for the Pentecostal/holiness stream has consistently outpaced that of conservative Protestants since at least 1955. Nevertheless, it peaked during the early 1980s at around 4 percent a year, has slowed ever since, and is currently on the verge of falling below 1 percent a year.

For the conservative Protestant family, the Yearbook data show a steady slowing of growth that goes back to at least 1955. Growth fell from over 3 percent annually during the 1950s to about 1 percent through the 1980s to less than a half percent through 2005, at which point Southern Baptist declines pushed the entire family into negative growth for the first time.

For oldline Protestants, the Yearbook data confirm a moderating rate of decline during the last 20 years of the 20th century, but show that decline reaccelerated at the turn of the century and that this stream of faith is currently losing members at a greater rate than ever before.

Why are evangelical Protestant denominations declining? While we await the definitive study, a few culprits seem likely. Studies suggest that the decreasing religious participation of each new generation of young adults is affecting virtually all religious groups.

The broad social and cultural changes sometimes referred to as “postmodernity” make religion in general and organized religion in particular a less credible option across the board. Traditional ways of doing church don’t work for increasing numbers of people, and institutionalizing new approaches is more difficult than most like to admit.

We also know that both the challenges of change and the corrosive edges of increasing diversity within memberships have raised denominational and congregational conflict to epidemic levels. Conflict impedes growth—for oldline churches but also for evangelical.

It is likely that the vitality of independent churches—including megachurches—is drawing people, and sometimes entire congregations and judicatories, out of denominational systems.

In any event, the dramatic decline in confidence in organized religion is unmistakable. According to the General Social Surveys of the National Opinion Research Center, the percentage of Americans who have a great deal of confidence in organized religion declined dramatically from 2000 to 2010—and the decline was nearly the same for evangelicals as for oldliners. Surprisingly, the biggest decline among any age group within these families is among older evangelicals. Among that group, the number expressing confidence in organized religion fell from 42 percent to 26. Indeed, this was the largest decline for any family or age group except among younger black Protestants—another ominous sign for an established segment of American religion.

Setting aside questions about historically black churches, it appears that racial, ethnic and immigrant communities are, along with Pentecostal/holiness and independent churches, the pockets of vitality within the overall decline. The Faith Communities Today report A Decade of Change in American Congregations 2000–2010 shows that the percent of congregations with a majority of racial/ethnic members increased from just over 20 percent in 2000 to just over 30 percent in 2010 (the report is available at faithcommunitiestoday.org).

Setting aside questions about historically black churches, it appears that racial, ethnic and immigrant communities are, along with Pentecostal/holiness and independent churches, the pockets of vitality within the overall decline. The Faith Communities Today report A Decade of Change in American Congregations 2000–2010 shows that the percent of congregations with a majority of racial/ethnic members increased from just over 20 percent in 2000 to just over 30 percent in 2010 (the report is available at faithcommunitiestoday.org).

The FACT national surveys of congregations further show that congregations in which racial/ethnic members constitute the majority are more likely than mostly white congregations to be growing and to include a significant number of young adults. The data are consistent with the claim increasingly articulated by denominational leaders, evangelical and oldline, that if it wasn’t for growth among immigrant and minority populations, they wouldn’t have any growth to speak of.

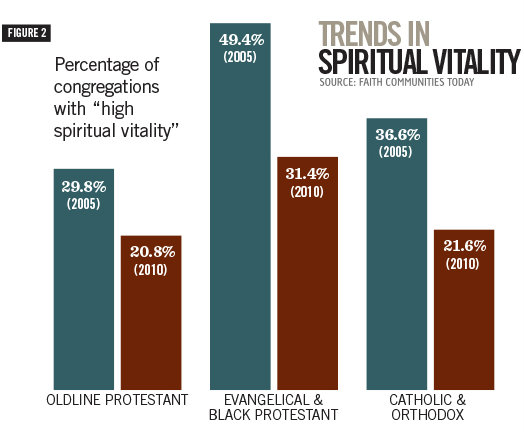

Numbers are not everything, of course. But markers for congregations’ involvement in social ministry and for congregations’ spiritual vitality—the latter related to an emphasis on prayer and scripture—are also troubling for all groups (see figure 2). According to the Decade of Change report, spiritual vitality dropped dramatically for all three families. Oldline Protestantism defined the bottom edge in both 2005 and 2010, but the greatest decline in the period was among evangelical and black Protestants.