Seeing through Piero

If you want to immerse yourself in the art of the early Renaissance Italian painter Piero della Francesca, you need to make a pilgrimage to several small Italian hill towns as well as to museums in London and Paris, Boston and New York City and Williamstown, Massachusetts. Many art critics attest that this is a pilgrimage well worth making. Piero’s paintings have the power to change lives, as art critic Peter Schjeldahl recently testified in the New Yorker (February 25). The serene dignity of his figures and forms “makes a viewer’s spirit sit up straight.”

So if you have the chance to see paintings by Piero della Francesca at the Frick Collection in New York this spring, don’t miss it. The exhibit gathers up all but one of Piero’s works held in American museums (plus a seventh from Portugal). Six of the panels come from the altarpiece Piero created for the Church of St. Augustine in Borgo San Sepolcro, his hometown. The seventh is a portrait of the virgin and child flanked by four angels, whose profound stillness and intelligence compel the attention of the viewer with an almost irresistible power.

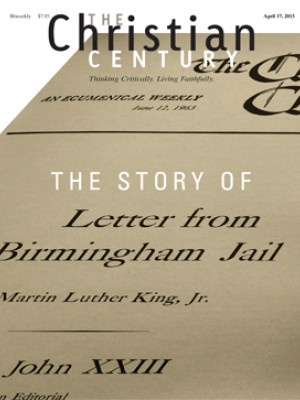

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The reviews of the exhibit have been enthusiastic, even rapturous, but they struggle to account for the religious quality of Piero’s art. The reviewers seem to want to hold Piero’s genius close while holding his religion at arm’s length. But is it possible to separate the painterly challenges that Piero set for himself from the religious ideas that he sought to explore? Is it possible to extract his artistic genius from his religious thought?

Walter Kaiser’s review in the New York Review of Books tries to do that (March 21). Kaiser focuses on the distinctive aspects of Piero’s craft that set him apart from other painters—the play of light in his work, his geometric approach to form. Kaiser regards Piero’s achievement as “a perfect union of art and science” born of a quality of mind marked by a mathematical and artistic perspective on the world around him. Kaiser makes no mention, however, of what Piero’s perspective as a Christian engaged in an artistic exploration of the themes of his faith might have contributed to this quality of mind and the achievement to which it gave rise.

Schjeldahl gives a more personal account of the power of Piero’s work. Recalling his encounter with Piero’s Madonna del Parto as young man, he considers that, in another time, the experience might have led him to a monastic vocation. Piero did lead Schjeldahl to a life of devotion—as an art critic.

Schjeldahl’s review is full of theological insight into Piero’s paintings. He notes that Piero’s gift for emphasizing the solidity and weight of his human figures illuminates the incarnational focus of his art. He points out that St. Augustine’s cloak, made of panels depicting the life of Christ, conceals the mysterious postcrucifixion episodes of that story in folds of cloth. He describes the small paintings depicting individual saints as “building blocks of piety,” suggesting their role in religious practice.

But ultimately Schjeldahl ends up in the same place as Kaiser, handling the religious thought that suffuses Piero’s work uneasily and keeping its religious quality at a safe distance. Piero’s religiosity leans toward the secular, Schjeldahl concludes, and his artistic achievement points to a future in which the Christian elements of works of art become “merely conventional.” This is a persistent theme about Piero. In 1925, Aldous Huxley insisted that what we find in Piero’s greatest works is “not Christianity, but a worship of what is admirable in man.” Kaiser and Schjeldahl concur, finding the human dignity and nobility celebrated in Piero’s art to be a classical ideal clothed in dispensable Christian garb.

What accounts for this diminishment of the Christian perspective of Piero’s grave and luminous paintings? Is it a worry that the Christian images will obscure the artistic innovations that paved the way, as Kaiser argues, for modern artists like Cézanne and Seurat? Does the profound admiration of the critics create such a deep identification with the artist that they downplay perspectives that they do not share? Certainly the diminishment of the religious quality of Piero’s art seems to depend upon an impoverished view of Christianity as wholly otherworldly and opposed to what is human. To this understanding of Christianity, Piero offers a powerful corrective.

It is by no means necessary to be a Christian to appreciate or to love or to be changed by Piero’s work. Anyone of any faith or none who stands before one of his paintings can experience what Schjeldahl describes as “a sense of being steadied and elevated”: such is Piero’s great gift to the human race. But that ennobling quality—the revelation that we are more than we even know ourselves to be—is not the opposite of Christianity but an embodiment of its bedrock convictions. In the art of Piero della Francesca, Christianity—far from being “merely conventional”—becomes a religious account of the world, one that reveals and illuminates the most profound possibilities our humanity holds.