Open door for terrorism: Christian-Muslim tensions in Kenya

The killing of Muslim cleric Sheikh Aboud Rogo on August 27 in Kenya’s Coast Province triggered the worst interfaith violence yet witnessed in that country. Muslim youths immediately rioted in Mombasa, burning down and vandalizing churches even as religious leaders on both sides called for calm. Three security agents were killed and 11 others injured in the ensuing chaos when rioters hurled a grenade at a police truck. The sheikh’s killer remains unknown. His supporters have pointed a finger at the police, an accusation the police deny.

This was only one incident in a year that has witnessed rising religious conflict. On September 30 a boy was killed when a bomb was hurled at a church in the country’s capital of Nairobi. On July 1, two grenades were hurled at worshipers at two churches in Garissa, the capital of remote North Eastern Province, which borders lawless Somalia. A total of 17 people died, including two police officers who were guarding one of the churches. More than 50 worshipers were injured.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

While Christians in Garissa had become accustomed to having Muslim youths throwing stones at church buildings, the recent attacks and the riots in Mombasa represent a major deterioration of relations.

The rise in violence is caused by both internal and external factors. Externally, Kenya’s military involvement in Somalia since October 2011—with the army fighting the al-Shabaab militant group—opened the country to the possibility of increased terrorist attacks. Kenya shares a long porous border with Somalia. This, along with the corrupt officials at the border crossings, ensures easy entry for any would-be terrorists. Initially, terrorist attacks focused on populated public areas—crowded streets and shopping malls—which made easy targets. A number of attacks have taken place in downtown Nairobi, the latest being in the Somali-dominated suburb of Eastleigh. Attacks have also taken place in Mombasa, Wajir and elsewhere.

With this campaign of terror, the attackers have hoped to wear down the Kenyan security machine and force a withdrawal of the country’s troops from Somalia. But the public has remained solidly behind the military’s efforts to tame Somalia’s warlords, and the military continues to delve deeper and gain more ground in Somalia. In July, Kenyan troops were incorporated into the United Nations–supported African Union Mission in Somalia.

The militants soon turned to attacking churches in the hope of igniting conflict between the country’s two major faiths. Indeed, the AMISOM campaign had long been portrayed by Islamists as an attack on the Muslim faith. Three weeks after the Garissa attacks, police seized explosives that were meant to be used against the Assumption of Mary Catholic Church in Umoja Parish in Nairobi. The two men arrested with the explosives had reportedly smuggled grenades and other weapons into Kenya.

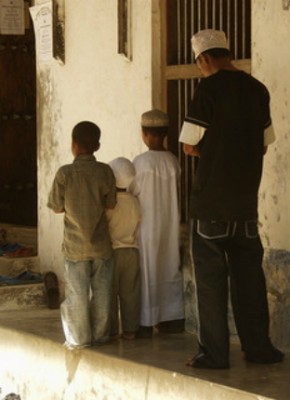

Internally, Kenya has long been plagued by conflict between Christians, who make up 80 percent of the country, and marginalized Muslims, who make up about 11 percent.

Most of the Muslim population lives in Coast Province and North Eastern Province. Historically, these are areas that have most suffered from bad governance in the postindependence era. In Coast Province, for instance, the question of land distribution has been a festering wound. With the coming of independence in 1963, land that had been taken by colonialists from the indigenous population did not revert to the locals but was instead appropriated by members of the ruling elite, mostly from central Kenya. The family of Kenya’s founding president, Jomo Kenyatta, is among those who own huge tracts of land in Coast Province. The local people were reduced to squatters on their own land.

About half of Coast’s population is made up of Muslims. Residents of Coast and North Eastern provinces often feel that governments are deliberately sidelining Muslims from participation in the national economy. In the Somali-populated North Eastern Province, whose people are predominantly Muslim, the extent of marginalization has probably been the worst in the country. Even obtaining a national identity card—a fairly straightforward exercise in the rest of the country—is a nightmare for residents of this province. They are often required to prove that they are Kenyan citizens by producing their grandparents’ birth certificates. The government justifies such measures by saying it is preventing infiltration into the country by non-Kenyan Somalis. It is quickly pointed out by opponents, however, that the measures applied to Somalis are discriminatory since they are not applied to other border communities such as the Maasai and the Luhya.

A 2010 report on International Religious Freedom prepared by the U.S. Department of State supported claims that Muslims were being unfairly discriminated against, particularly in the “issuance of identity documents and passports to Muslims.” The report also found that “counterterror operations violated existing national laws,” that “Muslims were unlawfully deported to foreign countries, that Muslim communities did not have fair access for obtaining land title deeds, and that the [Muslim subordinate] Kadhi courts were inadequately funded.”

A banned movement calling itself the Mombasa Republican Council has in recent years led calls for the secession of Coast Province. The huge grassroots support garnered by this movement has taken the government by surprise. Its rallying cry has been “Pwani si Kenya”—Kiswahili for “The Coast is not Kenyan.” The group is marshaling support for a boycott by coastal communities of Kenya’s general election scheduled for March 4, 2013. Although the majority of its supporters and officials are Muslims, Abu Ayman, editor of the Friday Bulletin and media officer at Jamia Mosque, points out that the main impetus is regional, not religious. He says the MRC is “a community movement” that includes Christians as well. “I don’t see religious tension breaking out over the MRC,” he said.

But Ayman himself points to a deteriorating environment for Muslims in Kenya. In an August issue of the Friday Bulletin, he reported that Islamophobes had demolished a mosque in Kajiado District, poured human waste in the mosque and set on fire copies of the Qur’an. The mosque was being built at Olkejuado High School and was nearing completion. The Bulletin also reported that the head teacher of Kangeta High School in Meru sent home 15 students after they insisted on observing the Islamic fast of Ramadan, defying orders from the school principal.

Ayman said that while Muslim leaders were vocal in condemning attacks against churches, Christian leaders did not reciprocate. “Issues affecting Muslims are not even mentioned by the church. Cases of intolerance are building up. If the simmering tension is left unattended, it will have serious consequences for the country.” The problem, said Ayman, is that there is no sincere effort to address the marginalization of Muslims.

The danger of an expanded religious confrontation is real, but Douglas Waruta, professor of philosophy and religious studies at the University of Nairobi, said:

Fortunately for Kenya, we have a lot of enlightened Muslims and Christians. They are the majority, and that is what has saved this country from a conflagration. The leadership of Supkem [the umbrella body of Muslim organizations in Kenya] is very responsible; so are Christian leaders. They have no agenda of creating conflict between Muslims and Christians. But they have to deal with the minorities within their communities. These minorities may sometimes be paid from outside Kenya. Foreign extremists employ our young people to cause trouble in the name of religion. We need to expand the healthy leadership we have among religious communities so as not to give space to fanaticism.

Waruta believes that Christians and Muslims must learn to be sensitive to one another’s traditions.

There are certain schools that were started by missionaries that have a very strong Christian tradition. There are also schools that have a very strong Islamic tradition. I think it is courting trouble when a Muslim demands that because we are equal, he wants to plant a mosque in this school with a long history of Catholic tradition. Neither can we have a Christian going to the island of Mombasa to put up a chapel in a school with a strong Islamic tradition. But you can build a mosque within the neighborhood outside the territory of the school. There are sensibilities that should not be ignored.

Waruta does not believe that discrimination against Muslims has been intentional. He said that although Muslims have been worse off than other groups both in precolonial and independent Kenya, the issues they complain of afflict non-Muslims as well. “I don’t think somebody sat down and decided they were going to create an injustice for Muslims or Christians.”

Notes Waruta:

Muslims did not benefit from missionary activity. They did not get the benefit of education because they were suspicious of it. I don’t think it was by design to exclude Muslims—Christians benefited the most because they were the ones starting the schools. It is the graduates of mission schools who became the movers and shakers of the newly independent Kenya. They happened to be Christians and were based in Nairobi. They did not care about Mombasa. We educated people in mission schools who thought in a certain way.

The coastal people “have been marginalized not as Muslims, but as coastal people,” said Waruta. “We have some people who are not Muslims in the region and who have suffered the same fate.”

Recent events appear to support this view. Intermittent clashes have also been reported in other parts of the country between various non-Muslim groups, mainly on ethnic lines. The clashes are mostly motivated not by religion but by competition for land and other resources.

But given the resentment by Kenyan Muslims of their Christian counterparts caused by a history of marginalization, it should not come as a surprise that international terrorist networks have easily found a sympathetic ear among local Muslim communities. It would be far-fetched to expect those Muslim youths who ordinarily find it a worthwhile pas- time to throw stones at church buildings to shed tears at the killing of innocent Christian worshipers. After all, they consider Christians to be responsible for their material deprivation.

Some Kenyan Muslim leaders believe that Christians could work harder to overcome the gap. Abu Sufian, a Muslim cleric, said, “Our mosques are open to all members of the public, but only tourists take up the offer to visit. Many Christians believe that if they came to the mosque, they would be attacked by jinns and demons.” Misgivings about Muslims, he says, have contributed to the view among Christians that Muslims are involved in terrorism.

Abu Ayman castigates Christian leaders for deliberately frustrating Muslims. Church leaders who sit on the boards of public schools, he says, have been responsible for the setbacks faced by Muslim students. A number of schools have prohibited Muslim girls from wearing the hijab and even defied directives by the Ministry of Education to allow the scarf in institutions of learning. Some schools, moreover, were forcing Muslims to attend church services, he said, and singled out Catholic-sponsored schools. The head of the Catholic Church in Kenya, Cardinal John Njue, was unavailable for comment.

As an example of the hatred perpetrated by Christian leaders, Ayman referred to a leading clergyman who is currently a member of parliament and who opposed the construction of a mosque in his constituency. The local population, Ayman said, was incited to demonstrate in opposition to the construction of a mosque that was meant to serve Muslims in the area.

Religious conflict in Kenya has not yet reached the scope that it has in Nigeria, but the possibility of further escalation exists. The entry of terrorist networks that fan religious animosity creates a particularly disturbing scenario. The al-Shabaab extremist group in Somalia is said to be cooperating with the global terrorist network al-Qaeda and other extremist groups. In June, media reports quoted the commander of the U.S. Africa Command, General Carter Ham, as saying that three of the “most dangerous” groups in Africa—North Africa’s al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Nigeria’s Boko Haram and Somalia’s al-Shabaab—are now coordinating their activities.

Waruta comments: “The most religious thing for us to be is to be human. And to be human means to seek justice [for] every citizen as a human being, not as a Muslim or as a Christian. We need to correct the unfairness of the past. Those Muslims making a lot of noise at the Coast should not be seen as enemies, but as people who are reminding us that we have an agenda yet to be settled.”