Mobilizing G8 on food

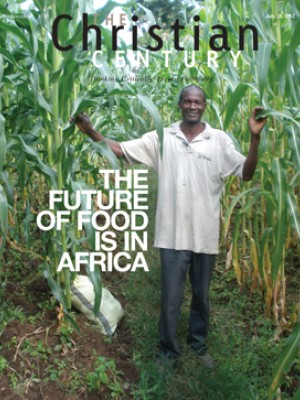

Read the main article on hungry farmers in Africa.

When leaders of the G8 countries met at Camp David in May, the proceedings were closely watched not only by experts in trade, politics and economics but by experts on world hunger. The Group of Eight, which includes representatives of most of the world’s largest economies, has become a key forum for addressing issues of food security and nutrition.

At President Obama’s first G8 conference in 2009, he convinced his colleagues to contribute $22 billion to agricultural development and food security. The amount was astonishing given that this occurred at the height of the global financial crisis. His success was evidence not only of his personal charisma but of how seriously world leaders had been shaken by the food-price crisis the year before.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In early 2008, riots swept through cities from Cameroon to Haiti in protest of dramatic rises in the cost of food caused by dwindling worldwide reserves of food, rising oil costs and natural disasters.

“The spike in food prices,” observed Eric Muñoz, senior policy adviser for agriculture for Oxfam America, “suggested that a breaking point was being reached. The kinds of policies that had been promoted around agriculture were not working.”

The $22 billion pledged was intended to support small-scale farmers, improve agricultural infrastructure and contribute to programs that prevent child and maternal malnutrition.

Asma Lateef, director of Bread for the World, said that 58 percent of the money promised has been dispersed, most of it through aid to smallholder farmers. But Gregory Adams, Oxfam America’s director of aid effectiveness, said that 30 countries still lack the resources to put their plans into action.

Muñoz said that no matter how well or poorly those dollars are spent, the money could only be understood as a “down payment” on a long-term investment in agricultural development. “Agriculture is not the kind of investment area where you can see immediate, massive results with one, two or even three years of funding. This requires decades’ worth of concentrated effort in order to see long-term progress.”

At this year’s G8 meeting, countries pledged only $3 billion over ten years to agricultural development, food security and nutrition. But John Kirton of the University of Toronto’s G8 Research Group said that food security organizations should be pleased. He noted that nonprofits and NGOs had been forewarned that money was tight, so any contribution should be interpreted as progress.

“We were told that there would be no new money,” he said. Another positive sign, he said, is that the initiatives are being led by Africa with donor monies as a secondary impetus, instead of the other way around. He believes that this arrangement has a higher chance of long-term success. In other words, the G8 promised to fund African-organized programs that would lead to sustainable development. African nations, local communities and NGOs were encouraged to develop programs based on local needs and then ask the G8 to fund what Oxfam’s Adams calls “shovel-ready” projects.

Perhaps because of the financial squeeze being felt by G8 countries, this year’s G8 conference mobilized a partnership called the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. The purpose of the New Alliance is to find new sources of funds through private partnerships. The roster includes 45 private companies that have pledged support. Partners include companies as large as the U.S.-based PepsiCo and as small as an Ethiopian coffee exporter and a Tanzanian seed company, Tanseed. The hope is that private partners will continue to fund projects that combine nonprofit and for-profit ventures with public-sector support.

It is a complicated vision, and the mere presence of multinationals like PepsiCo and Monsanto raises questions about how well smallholder farms will fare and how much accountability will be possible. Lateef said that organizations like hers will be watching carefully to see that “private sector funding does not crowd out public investment. We hope this isn’t a way for the G8 countries to say, ‘We don’t need to do as much.’”

Muñoz is skeptical of the New Alliance. In his view, the New Alliance has the potential not only to let donor countries off the hook for development projects but also to crowd out civil society and lose financial transparency. He predicts that the partnership “will not succeed without strong and consistent engagement of civil society in a way that we have not yet seen as the Alliance has taken shape.”

Lateef is more optimistic. She believes that the Obama administration, at least, understands the significance of food security and is a willing partner. The administration, she says, is articulating the connections between agriculture, food security, nutrition and national security. It is less clear if Europe, “in the middle of a meltdown,” is as committed.

One significant shift in global food discussions is the emphasis on nutrition. A series of 2008 articles published in the British Medical Journal demonstrated the social, economic and physical effects of malnutrition in the first two years of life. Malnutrition in this critical period can lead to poor physical and cognitive development that is largely irreversible.

Lateef said that people understand nutrition issues “in a much broader and richer way: it is about nutrition and smallholder farming, as well as hunger.” Lateef was hoping to see that new understanding reflected at this year’s G8, perhaps through an agreement on a target for reducing stuntedness in children caused by malnutrition. But that did not happen.

Muñoz said that supporting smallholder farms is critical to agricultural development. In Africa, partners like ROPPA, a regional member-farmer organization, have the political and social credibility to make considerable progress with proper funding from wealthier nations. Organizations like Oxfam and Bread for the World will work to hold donor countries and New Alliance partners accountable and ensure that money hits the targets.

“We are going to keep pushing,” said Lateef.