Congregations support imprisoned Somali men in Minnesota

Several churches in Minneapolis–St. Paul have funded in-prison education for young men convicted of ISIS involvement and also helped their families. It hasn't been without controversy.

In 2016 Abdirahman Daud was sentenced to prison for 30 years after he and several of his friends were convicted of plotting to leave the United States to join ISIS fighters in Syria. The men were arrested in San Diego in April 2015 before they had a chance to leave the country.

For the Somali community in Daud’s hometown of Minneapolis, the case is controversial. Many argue that the boys were entrapped by an FBI informant posing as jihadist.

“I just blindly followed everything that was told to me,” Daud said at his sentencing. Daud’s fiancé, Naema Ahmed, said he was only trying to escape FBI scrutiny. “We were all aware that he was being watched,” she said. Many Somalis question the length of the sentences imposed, since the men weren’t charged with actually harming anyone.

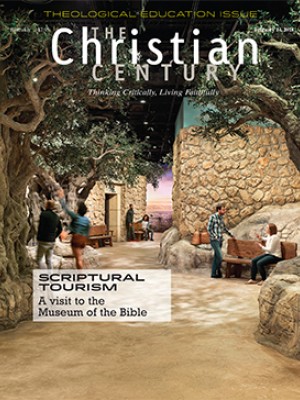

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Were the young men just expressing youthful bravado or did they plot against the United States? Were they victims of entrapment or willful conspirators?

Beth Minehart couldn’t sort out the complexities of the case, but when her congregation, Minnehaha United Methodist in Minneapolis, formed a support group for the families of the imprisoned, she joined in.

“Even when I just read it in the paper when it was happening, I thought, ‘They’re kids. They are so young. How can you put away children for so long?’”

Daud’s family is determined to pay for his education while he is in prison, and the Minnehaha congregation is helping to cover those expenses and to keep the young men connected to their families, as phone calls and email cost money in prison. Daud, 23, is studying engineering through Ohio University’s prison program.

“I can’t help but identify with the mother,” said Minehart, who has a 26-year-old son and helped raise a nephew who is the same age as Daud. “We’re not about figuring out whether they are guilty or innocent. I don’t want them having to justify themselves again and again.”

St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in St. Paul has also gotten involved in the case through the advocacy of one of its members, Matthew Palombo. A professor at Minneapolis Community and Technical College, Palombo is a longtime adviser to the school’s large Muslim Student Association. Though he did not personally know the young men leading up to the criminal case, he attended their trial and has become one of their leading advocates. Guled Omar was convicted as ringleader and sentenced to 35 years in prison in November 2016. Around that time, Palombo learned that Omar’s family was facing a crisis.

Omar’s older sister, who asked for her name to be kept private, was pregnant with her second child. The wages from her job had been paying the rent for the two-bedroom apartment housing her mother and her seven younger siblings. If she took a maternity leave, her family would not be able to pay rent, and Guled was no longer there to help.

When the priest at St. Mary’s, LeeAnne Watkins, learned of this situation, she called on clergy friends to cover the rent. Palombo’s wife, Leah, hosted a baby shower at the church. Watkins has become another advocate for the families, especially the Omars.

“Whether you believe [Guled Omar] did it or he didn’t do it, none of us is beyond redemption,” Watkins said. “When Jesus told us to visit people in prison, he didn’t ask us to check innocence or guilt first.”

People of the two congregations, along with St. Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral, have contributed more than $15,000 worth of support to the Somali men and their families. Watkins, her colleagues, and other donors have helped to pay the Omars’ rent over the past year and a half. The churches’ goal is to see that all of the men have access to education, even providing a scholarship for Omar’s younger brother to attend MCTC. Individuals are sponsoring Guled Omar’s education through Ohio University, and he in turn corresponds with them through a quarterly newsletter. “I refuse to give up and allow myself to go down the path of hatred and anger,” he wrote in the first letter.

The congregations’ connection to the Somali families has not been without controversy. Some people question why the churches are giving their attention to the Somalis when there are so many other people in prison and in need.

“Some people in the church just don’t want to see the church in the press,” Minehart said.

At St. Mary’s, the conflict has at times been pointed. Watkins was criticized for inviting Palombo to speak from the pulpit, where he challenged whether the convictions were just. A juror in the criminal case who heard about Palombo’s advocacy told him that Guled Omar would sooner blow up the church than accept help from it.

Watkins likens the Somali refugees to the biblical figure of Zacchaeus, the ostracized tax collector. “The two cultures that I think are the edgiest to align ourselves with now are Muslims and immigrants,” she said.

Abdirahman Daud’s aunt and fiancé spoke of how important he was in the neighborhood.

“Abdirahman would tutor all the kids,” Naema Ahmed said. “His character speaks to everybody.”

Ahmed believes that Daud did the right thing in pleading not guilty and refusing to testify against his friends. “I am glad that he did not lose his sanity. I’m glad that he did not trade his dignity for freedom. If he’s spiritually free, if he’s mentally free, that’s better for him and for us than if he were mentally incarcerated. They can still do a lot of good in the world from behind those bars.”