Why we miss Niebuhr now

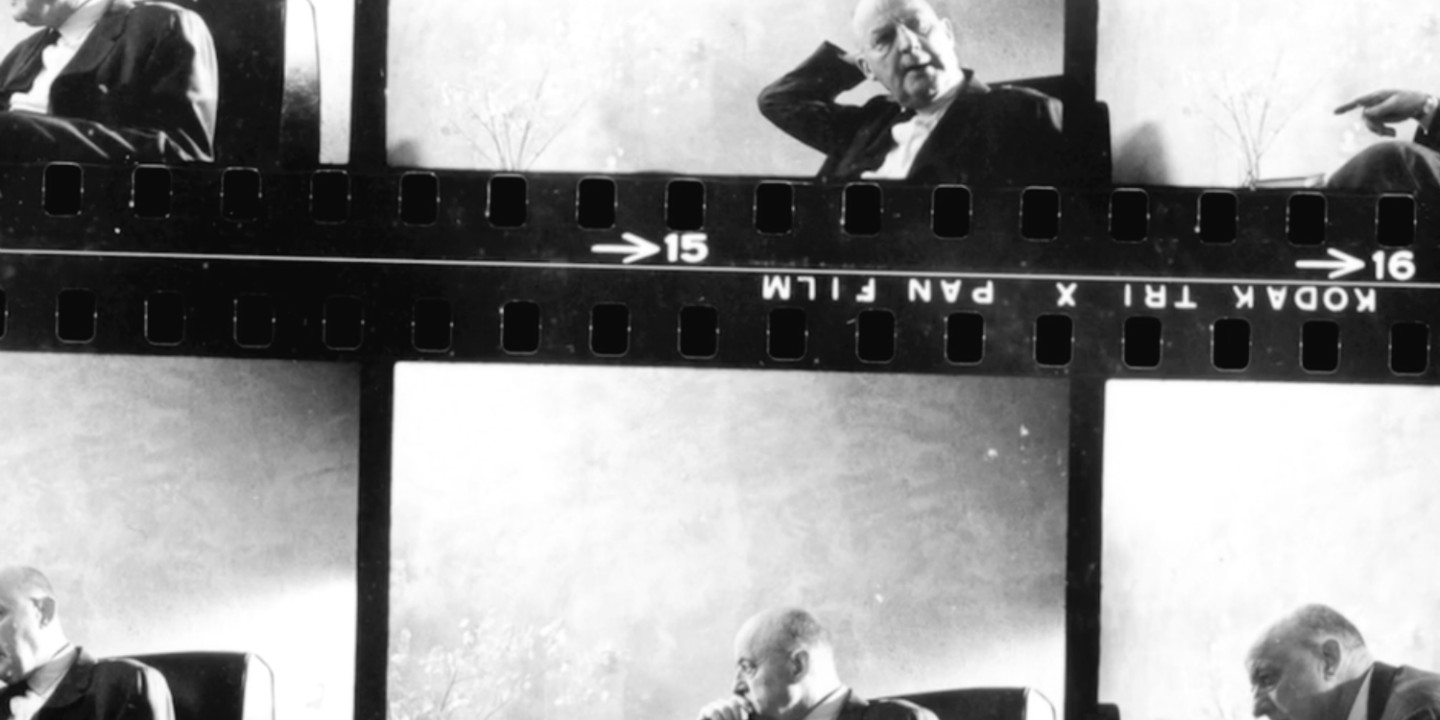

Martin Doblmeier’s new documentary shows how theology drives our use of power.

I once heard Stanley Hauerwas issuing one of his screeds against Reinhold Niebuhr when he was interrupted by a young theologian from England who asked, “So why do you care about Reinhold Niebuhr at all?”

The question was a sign of a theological sea change. For years Niebuhr was a dominant figure in Christian ethics and an unavoidable figure in theological education. It’s long been a theological parlor game to ask: Where have public theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr gone?

Martin Doblmeier’s terrific new documentary on Niebuhr, An American Conscience, reminds us just how essential Reinhold Niebuhr was. Among the luminaries who pay homage to Niebuhr are former president Jimmy Carter, New York Times columnist David Brooks, and historian Andrew Bacevich, a critic of the recent American military adventures. Doblmeier brings in footage showing President Lyndon Johnson awarding Niebuhr the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Martin Luther King Jr. quoted Niebuhr in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and in the film Cornel West talks about how King read Niebuhr in graduate school and concluded that African Americans had the resources to launch a movement of resistance to segregation. The film describes how Alcoholics Anonymous adopted Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer. His daughter, Elisabeth Sifton, says Niebuhr was slightly embarrassed to be famous for writing a prayer. The film also narrates his epic friendship with Abraham Joshua Heschel, who delivered the eulogy at Niebuhr’s funeral, and includes a moving tribute from Heschel’s daughter Susannah. Barack Obama, it is pointed out, was a Niebuhrian realist of sorts.

The film crackles with energy. Like his previous film on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Doblmeier does a good job showing the arc of a life.

To some extent, Niebuhr was a “yahoo from Missouri,” as his daughter recalls. He was a first-generation American and, in a detail Doblmeier does not belabor, a native German speaker. He needed an assistant at Eden Seminary to help him with English, yet graduated as valedictorian. His father, Gustav, was his delight and role model, which was not the case for his brother Helmut Richard, who found their father authoritarian. Sifton weighs in on the difference between the brothers and notes that Reinhold himself thought his brother was the better thinker. “I have the gift of gab,” she records her father saying of her uncle, “but Helmut is the better theologian.” The differences between them came up in their only public feud: when Japan invaded Manchuria H. Richard wrote a famous essay on “The Grace of Doing Nothing.” Reinhold found it dangerously naive.

Reinhold began pastoral ministry in Detroit, where he penned my favorite book of his, not mentioned in the film, Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic. He tried to awaken corporate executives, bankers, and other eminences in his congregation to the social ills of racism and worker exploitation. He mused for the rest of his life on the way people can be good as individuals but corrupt when acting as a group. He came to describe that intuition using the symbol of original sin. When he left Detroit for Union Theological Seminary in New York, African-American churches held services of appreciation.

At Union, I was surprised to learn, he was not universally well received. Though seminary president Henry Sloane Coffin had been impressed by his activism and his writing in places like the Christian Century, the rest of the faculty was aghast at his having no doctorate and nearly voted not to appoint him. Soon they realized they might have to struggle to keep him. His classes filled to overflowing. He taught Bonhoeffer and helped convince faculty colleagues, in the midst of the Great Depression, to take a pay cut to bring Paul Tillich from Germany.

As the cold war gained steam, Niebuhr thundered at the Manichaeism that viewed the Soviet Union as altogether evil and the United States as altogether good. J. Edgar Hoover’s file on him eventually ran to 600 pages.

Niebuhr spent a career writing “big books on big subjects with big public stands,” as Brooks said. Sifton tells of the way her father could write fast, amidst chaos. And could he ever turn a phrase: “Nothing that is worth doing can be achieved in our lifetime; therefore we must be saved by hope. Nothing which is true or beautiful or good makes complete sense in any immediate context of history; therefore we must be saved by faith. “

Niebuhr is still read, and West describes Moral Man and Immoral Society as still the most important book in Christian ethics. But Niebuhr’s historical moment seems to have passed.

Hauerwas argues that Niebuhr could assume one thing we cannot—the presence and influence of a strong mainline church. Perhaps that explains why the church is largely absent in Niebuhr’s theology (though it is lovingly described in Leaves). Furthermore, Niebuhr’s own use of Christian tradition relied heavily on using Christian terms—like sin, hope, love, and forgiveness—but applying them in ways that seemed to leave the particulars of Christian doctrine behind. That’s why a group like Atheists for Niebuhr could exist.

Are there heirs to Niebuhr? If there are, would they be figures like Jerry Falwell or Franklin Graham, who speak as though America were the church? Jim Wallis? Marilynne Robinson? Might Trump adviser Steve Bannon, in a peculiar way, be a kind of Niebuhrian figure, whispering in the ear of the president and providing his own theological vision about how to use power?

The return of Reinhold Niebuhr may not be all we need. But it would help.

A version of this article appears in the March 29 print edition under the title “Why Niebuhr mattered.”