August 8, Ordinary 19B (2 Samuel 18:5–9, 15, 31–33)

David, Absalom, and the dangers of “hanging between heaven and earth”

David wants his throne back, but to get it he will have to fight his own son. Yet the tale of David and Absalom is not exactly a conflict of interest story because—and here comes an understatement—these two have history. There are plenty of reasons that each would want the other’s head. What happens isn’t quite a catch-22 either, because there is a clear victory. It could be seen as a Pyrrhic victory, but this story is about something more than a clear victory that comes at great expense.

The story, brought to a tragic climax in this week’s reading, is about a phrase that lingers in the text, seemingly on purpose: “hanging between heaven and earth.” This phrase describes, almost to a comic effect, what happens to Absalom as he is riding during the battle: his head gets caught in a tree’s branches. Yet he remains alive, “hanging between heaven and earth,” while his mule rides on.

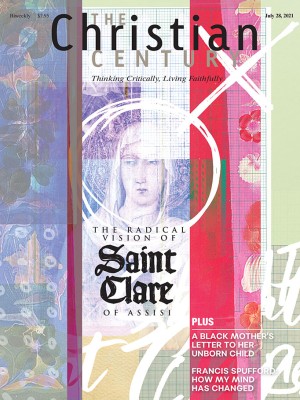

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

He’s not the only one hanging between. David wants all the might of a political giant, complete with a comeback story that would make Napoleon blush, yet he also wants his son spared. The text pushes even further: David wishes he could trade places with his dead son. Yet in the moments leading up to battle, and in all the engagement between armies and advisers (that Joab!) and prophets, David believes fully that he can be both a faithful father and a powerful warrior.

This delicate balancing act is both ancient and modern. We heed our financial adviser’s advice to add cryptocurrency to the portfolio, and we also want to protect the environment. We want our children to have the best possible education, and we want to support local public schools. We want to be on the right side of history with regard to racism, and we want little to do with the personal, political, and economic deconstruction that antiracism requires. This is often called “paradox” or “tension,” but this text offers us a different image: hanging between the vision of God and the practicalities of our earthly existence.

It isn’t until David finally chooses one and loses the other that he realizes the gravity of the mistake he’s made. Some might call this retrospect, and they’d be right. But that really is too soft a way to describe what is set before us here. David’s cry of anguish is spelled out verbatim, as a way of emphasizing a kind of distress and knowing-too-late that is the point of the story. “Retrospect” tends to describe a knowing that informs our future (“now that I know better, I will do better”). David has no future. His decision has cost him everything that means anything.

It has revealed that, for all his political maneuvering and absolute strength as a king, what David wants most—what he feels at his innermost core—is the yearning to restore his family. After years of brutality against each other, digging their heels into the ground and finding every way to embarrass the other, what David and Absalom asked for, what they made happen, what they got was a nightmare that will no doubt haunt David for the remainder of his life.

This is the danger of hanging between heaven and earth. Looking at this text, we have to consider the gravity of our decisions and actions in light of who we hope to be in this world. We have to consider how God calls us not to choose between heaven or earth but to live “on earth, as it is in heaven.” David’s failure to do so does more than create a Pyrrhic victory or a conflict of interest. His pursuit of victory eliminates the victory altogether.

This is related to the warning Jesus issues about serving two masters. It’s the same indictment God’s prophets throughout the ages have delivered to nations and people. At a certain point, whether by choice or by force, who we are is laid bare within our souls and before the world. And should we choose politics over faith whenever the two may collide (that is to say, often), we are likely to echo the regretful response of J. Robert Oppenheimer—famously known as the “father of the atom bomb”—when he witnessed the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” said Oppenheimer, quoting the Hindu Bhagavad Gita. This is as gut wrenching as David’s own cry: “O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!”

This story of king and would-be usurper—of father and son—is laid before its audience as an analog of the choices and opportunities we encounter on a daily basis, both in community and in our private lives.