When Israeli settlers meet West Bank Palestinians

“How had I not heard these stories and met these people, living 30 years right next to them?” asks Hanan Schlesinger. “How could it be?”

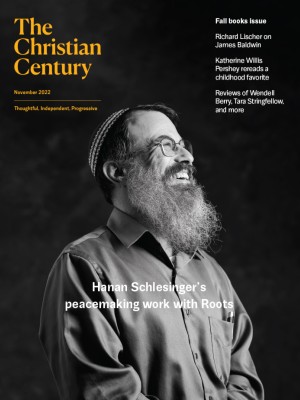

Hanan Schlesinger, an Orthodox rabbi who lives on the West Bank, is director of international relations for Roots/Shorashim/Judur, which he cofounded with Ali Abu Awwad and Shaul Judelman. Since 2014, the organization has facilitated unmediated, face-to-face connections between Israelis and Palestinians. It meets on land owned by Abu Awwad’s Palestinian family.

How did your career prepare you to help found Roots?

I am an Orthodox rabbi. I’ve found myself often working with or advocating for those who are considered to be the other from that perspective. That means working to advance women’s place within Orthodox Judaism. It means working to integrate Ethiopian Jews into Israeli society. It also means working with Reform and Conservative Jews. For a long time the other, for me, was almost always within the Jewish world.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

That began to change when I went to Dallas in 2005. A pastor friend and I founded an organization there called Faiths in Conversation, in which deep friendships and conversations developed between Jewish, Christian, and Muslim people of the cloth. That really expanded my horizons. It enriched me and made me a more humble person.

The full name of your organization is trilingual: Roots/Shorashim/Judur. How do you find a common language for the sort of conversations your group inspires, which are often about things people don’t even know they are thinking?

It’s become clear to me and to my Israeli and Palestinian partners that in most situations there’s very little we can say to convince our own side to take into account the other side: their existence, their legitimacy, their claims, their suffering. It turns into a shouting match.

But what I can do is convince my neighbor to meet a Palestinian. The formula, the key, the secret is the face-to-face, interpersonal contact with the other.

How do you convince people to have these encounters?

It’s not easy. But there are some people that have curiosity, some openness to meeting the other side. By and large, there’s more curiosity to meet the other side than there is a willingness to listen to me pontificate.

Let me tell you a story that one of our Palestinian partners tells us. His name is Noor. He’s in his late twenties, and he has this group of friends that he tried to convince to come to Roots. He told them about the work we do, about me. It took him a long time to convince them to come, and eventually they came. Afterward they said, “Noor, why didn’t you tell us?” And Noor said, “I did! I did tell you!”

You can’t hear the words until you’ve had the experience. It just doesn’t penetrate.

What about you? How did you come to have these encounters with Palestinians?

For me, it started with hitchhikers. I picked up some hitchhikers, and when they left the car, I told the guests from overseas who were in the car with me that I try to pick up every person that sticks out his finger. Then I realized it wasn’t true. I only picked up Jewish hitchhikers. I felt an embarrassing moment of revelation. It’s embarrassing to have it revealed to you in the presence of others that you don’t see what’s going on around you.

I began a journey to try to meet Palestinians. The real turning point was the last Wednesday of January 2014, when someone on Facebook helped me come to a face-to-face meeting with Ali Abu Awwad and many other Palestinians. This was the first time that I met Palestinians for real.

I was challenged and confused and devastated and undone. The bottom started falling out of my self-perception. A lot of things happened in those three hours.

First of all, there was the experience of just talking to them and realizing they have stories. Some of the stories were about personal transformation, about meeting Israelis and being transformed, about discovering that we’re not all just enemies.

Then I heard their stories of their history, of the way they experience themselves, and of the way they experience my people. It was like hearing history backward. I was hearing the same timeline—the Balfour Declaration, the war in 1948, the war in 1967. But my “triumph of the Jewish spirit”—the return home after 2,000 years—was for Abu Awwad his tragedy, his Nakba. And 1967 for him was the beginning of occupation. These Israeli soldiers—who I’m so proud of, and I myself served—suddenly the soldiers were bad. It was so, so confounding.

How had I not heard these stories and met these people, living 30 years right next to them? How could it be? First, that they’re saying things that can’t be true. Second, how could I have never heard these things? Third, perhaps they are true?

From that moment I started feeling nauseous. I remember the feeling of nausea so clearly, how it accompanied me for days and returned periodically during the early years of Roots.

You said at one point that you weren’t sure if you were permitted to keep listening. What did you mean by that?

They were saying things that contradicted what I knew to be true. I had a sense of weakness or of being a traitor, that I was allowing myself to listen to this falsehood. Both sides experience such thoughts during this kind of encounter. There’s a sense of, How far can we go? How far are we allowed to go?

A year after this, when I was already going on speaking tours with Abu Awwad, we went to a laundry room on the college campus where we were staying. We both asked ourselves, Am I allowed to put my laundry in the same machine with his? Can an Israeli really put his dirty underwear in the same washing machine as a Palestinian’s?

As we were waiting for our laundry, we saw a Ping-Pong table. We kind of looked at each other. Can we play together? Are we allowed to do this? Are we going too far? We’re supposed to be enemies!

We started playing. We were very evenly matched, and we had fun! Are you allowed to have fun with a Palestinian?

Today I think the question of going too far is ridiculous. On the last evening of our first speaking tour, we spoke at a church in Amarillo, Texas. Afterward, Ali was going one place and I was going another. He and I hugged as we were parting. It was one of the most powerful hugs I have ever experienced. I felt I was parting from a part of me. I felt he had given me so much. And I felt the tears just dripping down.

I witness the same type of transformation I went through and am going through. I get to see that every week in other people.

What happens at a Roots meeting?

We simply create a neutral, safe space, and in that safe space we conduct a variety of activities, including unscripted open houses. Come have coffee and talk to that person who lives a mile away from you that you’ve never seen. You’ve seen his silhouette only, but all you’ve seen is an enemy. He hasn’t yet become more than two-dimensional.

More often the activities are programmed on specific topics. We have photography workshops. We have Ramadan dinners. We have music, religion, drama, lectures. Food helps. Music helps.

Roots is not political—we’re not a political movement. But we are having a deeply political effect, because we’re changing people’s ultimate understanding of who they are, what they’re doing here, and how they should be living their lives. I call it pre-politics.

Creating a safe space doesn’t sound so simple in Israel/Palestine. How do you do it? And how do you gauge whether it’s working?

We live in the West Bank, aka Judea/Samaria, in completely and utterly segregated communities. The only place that there’s mixing is on the roads—not even all the roads, just some of them. You see the other through his windshield. We have different colored license plates.

A very small number of Israelis and Palestinians work together, but never make the mistake of thinking that contact between an employer and employee is even similar to getting to know a person. People sometimes fool themselves.

So then, how do you do it? The first step is to find a space that’s not in an Israeli or Palestinian village.

We have use of such a piece of land. It’s Palestinian farmland on the same piece of land where I first met Palestinians. It is right off a main road where thousands of Palestinians and Israelis pass every day. So it’s pretty comfortable—not perfect—but pretty comfortable for both sides.

There’s nothing imposing there; there’s nothing that immediately turns Israelis off. There are no signs in Arabic, no signs in Hebrew—there are no signs at all! It’s a homey place on which Ali built a log cabin; we built two classrooms, bathrooms, and a patio. So the space is crucial.

In addition, the other founders and I somehow have created a culture of hospitality, of openness, of accepting. It’s hard to say how we did it; there’s no formula there. Most of the people who come feel welcome, I think.

Do you have role models, people you’ve learned from about how to offer hospitality?

In little, subtle ways, Palestinians are always teaching me hospitality. They have a culture that is much more based on family, hospitality, and honor than the Jewish culture I’m part of. The Palestinians just know how to welcome you, how to give you food and drink and make you feel comfortable. I’ve learned from that and have come to honor it.

And that translates to Israelis? It doesn’t feel foreign to them?

No, it feels good.

We have created this atmosphere in which you come to listen—you never come to tell someone who they are. You come to listen and to let them tell you who they are. And then they may listen when you tell them who you are. But you’re not telling them what to think. You’re just telling them: this is who I am. It’s not a political truth you’re asking them to accept; it’s just who you are.

Are there moments when people start to feel like those larger truths are being discussed? Or have you found ways to avoid that?

The normal way of things is to generalize. You’re a Palestinian, so all the things that have been done wrong to me by Palestinians, you did them. And the opposite.

A good example of this is that Palestinians suffer quite a bit from Israeli checkpoints. Their freedom of movement is restricted, and they are humiliated at checkpoints. So let’s say a Palestinian comes to Roots for the first time and has been detained at a checkpoint on the way. This has happened many times. Sometimes Palestinians coming to our center for the first time carry a lot of anger, and they tell the Israelis, “This is what your people did to me!”

We Israelis have learned that our job is to listen. We listen and express empathy. And the next time the Palestinian comes, if he’s been detained again on the way by the Israeli army, he’s not going to say, “This is what you did to me.” He’s going to say, “This is what the soldiers did to me, but I know you don’t agree with the soldiers.”

Most of the Israelis who come to Roots activities don’t really know the degree to which our lifestyle is impinging upon and deeply harming the Palestinians. We just don’t see it. That’s part of the transformation. People begin to realize how our way of life has been deeply one-sided and has trampled on the Palestinian connection to the land and Palestinian rights.

You describe yourself as a “passionate Zionist settler.” What do you mean by that, and how have you been able to embody that in a way that is meaningful to you and that your Palestinian friends can hear and understand?

For me, the return of the Jewish people to the land of Israel after 2,000 years of exile is big. It’s meaningful, and it changed my life. Almost everything about me is intertwined with the fulfillment of the Zionist dream, which is the fulfillment of the Jewish dream of 2,000 years: to come home.

And I came home, as I often say, to the center of the land of Israel. Not to the periphery. The periphery is the coast, which is not where the Bible was written; it’s not where the Jews lived for the 1,000 years we lived in the land. The Bible was written and the Jewish people lived in the central mountain range, which today is called Judea and Samaria—the West Bank. So I’m passionate about my connection to the land of Israel and to the cradle of biblical and Jewish civilization.

But you don’t have to be wrong for me to be right. I’m right in the sense that the experience I have of connection to the land is real. But that doesn’t mean that your connection to the land is not real. It’s not a zero-sum game.

I really want Christians to understand that this is our sense of who we are and of our mission in this world: that we are a particular people. We want to remain a particular people. And we are deeply, deeply, historically connected to a particular piece of real estate, which to us is the Holy Land, in the most visceral sense. We want to live in that land, and we want to cultivate a Jewish culture in that land. For me, that’s a fact of identity.

One of the problems is that most of my people are infected with a disease I call “the hubris of exclusivity.” I agree with all my neighbors that this is the land of Israel, and in a certain sense it’s our land. But I don’t agree that it’s only our land. It’s another fact of identity that it’s also Palestinian land. It’s a fact of identity and history. You can’t get around it. The little piece of land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea that includes the West Bank and the state of Israel is all Israel—but it’s also all Palestine.

I said these words near the end of the first year of Roots. I trembled when I said them, because they contradict what I had been taught. I was taught, again, the hubris of exclusivity: that it’s only ours, that the Palestinians don’t belong here. Just like the Palestinians have been taught that it’s all theirs and the Jews don’t belong here. But the terrible tragedy is that we both belong here.

And the gift, maybe.

Exactly.

You’ve written that because there are religious sources to the problem, there also need to be religious sources to the solution.

Let’s go back a little bit. During the course of the Israeli and Palestinian peace movements—we’re talking decades—it’s almost always been the humanistic or universalistic movement of meeting the other as a human being. Of course, that’s great, I’m not against it. But it has ignored or swept under the rug the particularist identities on both sides.

It means that the people who have the strongest sense of their particularist identity aren’t welcome to the dialogue, and even those who come to the dialogue feel more comfortable leaving their particularist identities at the door.

The work we’re doing at Roots is very different. It’s about involving the people who have the strongest particularist identities, both Palestinians and Israelis.

The passion for faith certainly unites the two sides. The passion for the land unites the two sides. Introspection and repentance are values in Judaism and in Islam. The scriptures of Islam and Judaism are very similar: the stories, but even more than that, the legal structure. People are blown away when they realize! It’s so similar, it takes the breath out of you. You have to rethink: How could it be that we’re so similar?